In the Shadow of Stone Mountain

The past, present, and future of the African-American community are nestled beneath the country’s largest Confederate monument

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/ee/62ee339f-1030-4a45-adbd-8898a121cedc/img_8465.jpg)

Stone Mountain looms over the surrounding landscape like the back of a great gray beast, a speed bump on an otherwise smooth ride above the flat treetops of Georgia. The mountain stands out as something that doesn’t belong, and for that reason, it draws your attention. It’s also received the notice of the national press for years, whenever a conversation regarding Confederate culture and heritage—most recently centered around Civil War monuments—has arisen. This isn’t surprising: the massive rock carving on the north face of the mountain depicting Confederate generals Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson is the largest bas-relief in the world. A laser show on the carving is featured every Saturday night in the summer and fall, one in which the three horsemen seemingly gallop out of the rock. Later in the laser show, Martin Luther King’s visage is projected onto the monument, a recording of words from his “I Have A Dream” speech washing over the lawn where spectators watch. But when the show is over and King is gone, the generals remain.

The monument is generally the sole thing people think about when they hear Stone Mountain, and recently Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams called for it to be taken down. Because it is, and has historically been, a testament to white supremacy. But at the base of the mountain sits Stone Mountain Village, and within it the African-American neighborhood of Shermantown, which managed to survive and persevere under this legacy.

This small community is slowly fading into history, but deserves to be remembered in order to ensure that the debates around Stone Mountain don’t erase those who live in its shadow. The stories of the Confederacy and its generals shouldn’t have an unchallenged monopoly on the discussion. The achievements of the residents of Shermantown might not seem extraordinary, but they reflect the realities and context of the setting within which they were accomplished. Without recognizing the lives of Shermantown, any narrative about Stone Mountain is incomplete.

***********

Stone Mountain has long been an attraction for people, dating back thousands of years. Native American nations such as the Cherokee, Creek and Muscogee settled in the area up to 8,000 years ago, long before white settlers moved in in the early 19th century. Quarries were dug initially in the 1830s, pulling granite and other stone from the mountain, but the industry boomed after the completion of a railroad to the village and quarry site over the following decade, which allowed for the stone to be more easily transported. The name of the village was changed to Stone Mountain around that time.

Shermantown, derogatorily named after the Union General William Sherman—whose “March to the Sea” cut a swath of destruction from Atlanta to Savannah—came to fruition after the Civil War. Its founding followed a pattern of development seen across the South, in which newly freed African-Americans moved in search of work but were denied places to live in existing communities due to segregation. Stone Mountain Village was no different, and thus became the upstart neighborhood of Shermantown.

Stone Mountain was sold to Stone Mountain Granite Corporation for $45,400 in 1867, and nine years later sold again for $70,000 to the Southern Granite Company, owned by brothers Samuel and William Venable. In 1915, Stone Mountain served as a launching pad for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, of which Samuel Venable was an active member. He allowed a cross to be burned on the grounds in 1915, granted the Klan an easement (the right to use and enter onto the legal property of another) to the mountain in 1923, and leased the initial land for the Confederate monument that stands today. Their nephew James Venable, a one-time mayor of Stone Mountain Village in the late ’40s, would go on to continue this legacy as a Klan leader from the early ’60s to the late ’80, hosting rallies on the Stone Mountain grounds.

Gloria Brown, 77, was born in Shermantown and continues to live there today. She looks back on her childhood there with fond memories and is frustrated that the debate over Stone Mountain ignores her community. “We had black people that worked ‘round there, they had a granite company around there, and a lot of black people worked at that granite company. They drove trucks, they mined the granite, they were masons. When I was younger and all, we had people that lost their lives working on that granite. But nobody ever mentions that.”

She characterizes Shermantown as a striving community for the simple reason that there were so many African-American people that lived there or worked on the mountain, long before the Confederate carving was completed in 1970.

Stone Mountain granite, quarried by the African-American laborers from Shermantown, not only built churches in the area, but also the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the east steps of the U.S. Capitol, the dome of the Federal Gold Depository at Fort Knox, and the locks of the Panama Canal, just to name a few.

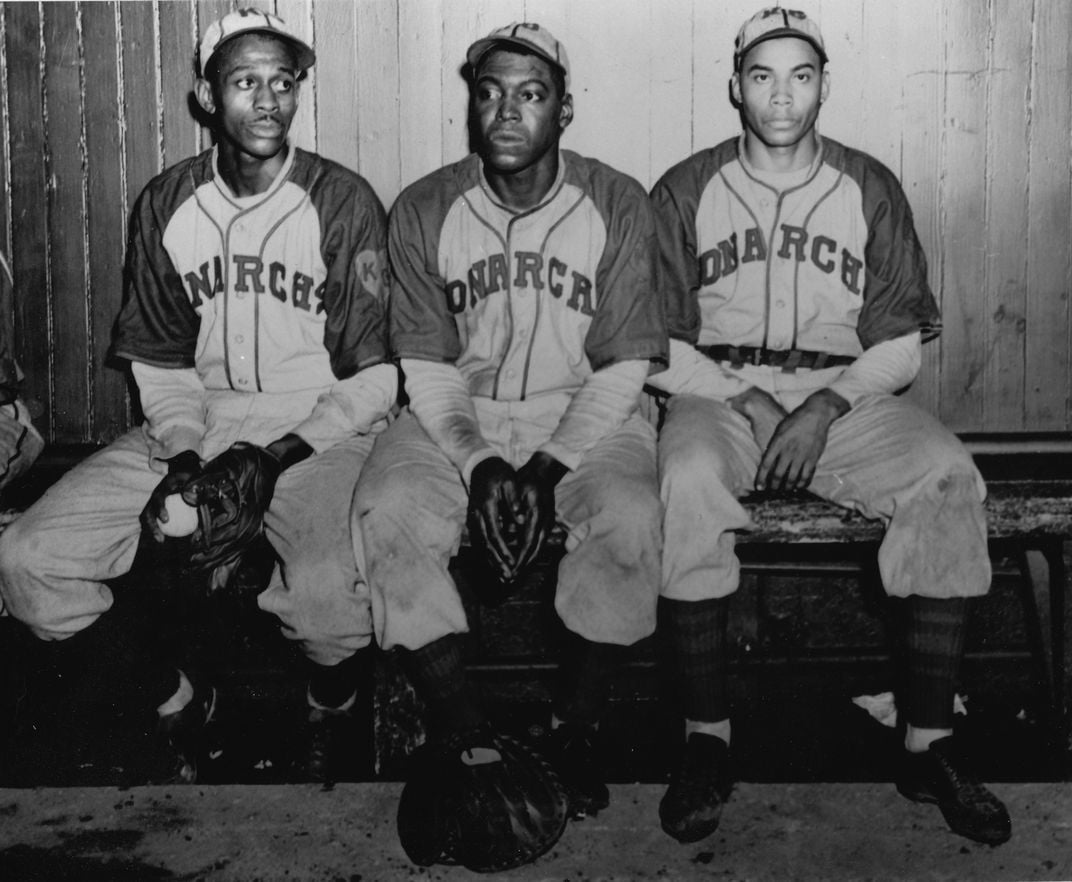

Beyond those workers, neighborhood native children include one of the top players on the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs and catcher for the legendary Satchel Paige, Joe Greene, and Victoria Simmons (one of the first woman to graduate from Spelman College). Stone Mountain Village was also the birthplace of modern-day entertainment visionary Donald Glover.

Rusty Hamby, a history teacher who has been teaching in South Dekalb County for 33 years, and whose family has lived in Stone Mountain Village for generations, believes that by centering the national conversation around Stone Mountain on the monument, other important stories get crowded out.

“If the history of Stone Mountain is a 23-chapter book, we’re continuously reading one chapter,” he says. “Stories like those of Joe Greene and Victoria Simmons are important ones that you never hear about,” he says.

James “Joe” Greene, born in Shermantown, began playing professional baseball in 1932, and went on to catch for the Kansas City Monarchs pitching staff in the 1940s, which featured the famous Satchel Paige. According to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Greene was credited with 33 and 38 home runs in 1940 and 1942, leading the league in those years. “He was one of the unsung stars of the ‘blackball’ decades,” reads Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues by historian John Holway.

Following a Negro World Series win, Greene, like many others, joined the armed forces to fight in World War II, where he served with the 92nd Division in Algiers and Italy and spent eight months fighting on the front lines. Greene returned to baseball after the war, but never regained the form he had prior. He ended up back in Stone Mountain Village and worked for Sears.

“Things have changed a lot,” Greene told Holway. “It takes time. I’ve always lived in the South. I was raised around this little old village here, Stone Mountain.... It seems that now, people would be intelligent enough to get away from some of these [racist] philosophies. Because they hurt, they hurt, they really hurt.”

The baseball field that Joe practiced on, and that the Stone Mountain pro team used to play on, is now gone. It was replaced by a local elementary school named after Victoria Simmons. Born in 1866, Simmons attended Spelman Seminary (now Spelman College), just seven months after it was founded, and would go on to graduate with certifications that allowed her to conduct missionary work, teach, and work as a nurse. The daughter of enslaved workers, Simmons recounted that her father, when he gained freedom, “was at once accepted as leader of his people. He went on to found the first school for Negroes in DeKalb County.”

Today, Stone Mountain Village faces disproportionate traffic jams for its size, as 4 million visitors a year pass through it en route to Stone Mountain Park. The village, particularly the main street next to the old train station, offers a quaint mix of stores and restaurants, while some side streets feature recently remodeled houses. There are only a couple of signs that still bear the name Shermantown in the village. One is an official historical sign whose arrow points down a road behind the village municipal offices, declaring "Historic Sherman Town", an invocation of something from the past, but no further details as to what it might be. The other is the name of a playground on a road that dead-ends into an area that used to house the Stone Mountain prison. The Victoria Simmons school is also gone, replaced by The View, a senior living community off of Venable Street, named after the Klan family. Outside of these two signs, there is little that identifies Shermantown as a neighborhood that ever existed.

The people I spoke to painted a picture of Stone Mountain Village of one where the community overcame the racism of the Klan, where small town living trumped prejudices. But in a recent Esquire profile of comedian and entertainment impresario Donald Glover, who was born in 1983 in Stone Mountain Village, a darker picture of the community is offered.

“If people saw how I grew up, they would be triggered,” said Glover. “Confederate flags everywhere. I had friends who were white, whose parents were very sweet to me but were also like, ‘Don’t ever date him.’ I saw that what was being offered on ‘Sesame Street’ didn’t exist.”

As Shermantown starts to fade, so too do the stories of the people that lived there, surviving and at times, thriving in the shadow of a mountain that has come to stand for one thing only- its Confederate monument. Ignoring wrinkles in that story, such as that of Shermantown, lets a monolithic tale be written by the Venables of the world, while Shermantown is consigned to memory, eventually to be forgotten entirely.