How a Single Paragraph Paved the Way for a Jewish State

The Balfour Declaration changed the course of history with just one sentence

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/f7/1af7bc53-748d-47c8-ac92-a2fdc43ac680/balfourdeclaration_1917229.jpg)

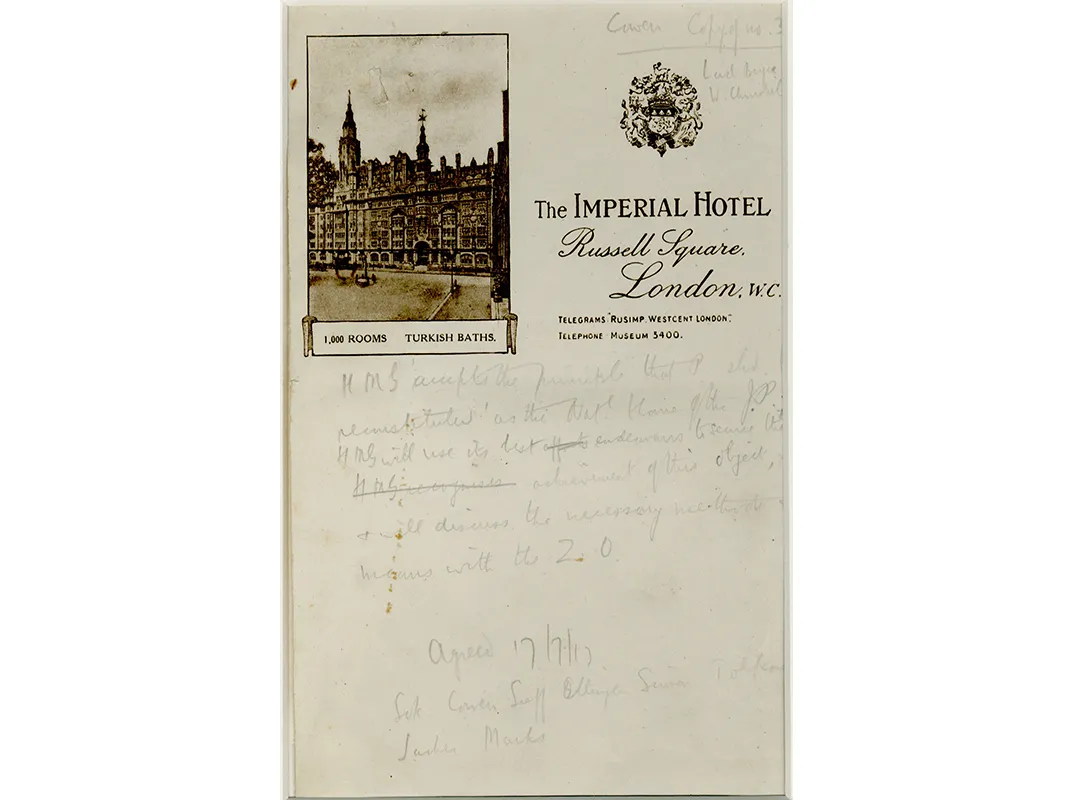

Upon first glance, the two pieces of paper, covered with scribbles and scant in text, look like unassuming notes. In truth, they are drafts of a paragraph that changed the course of world history.

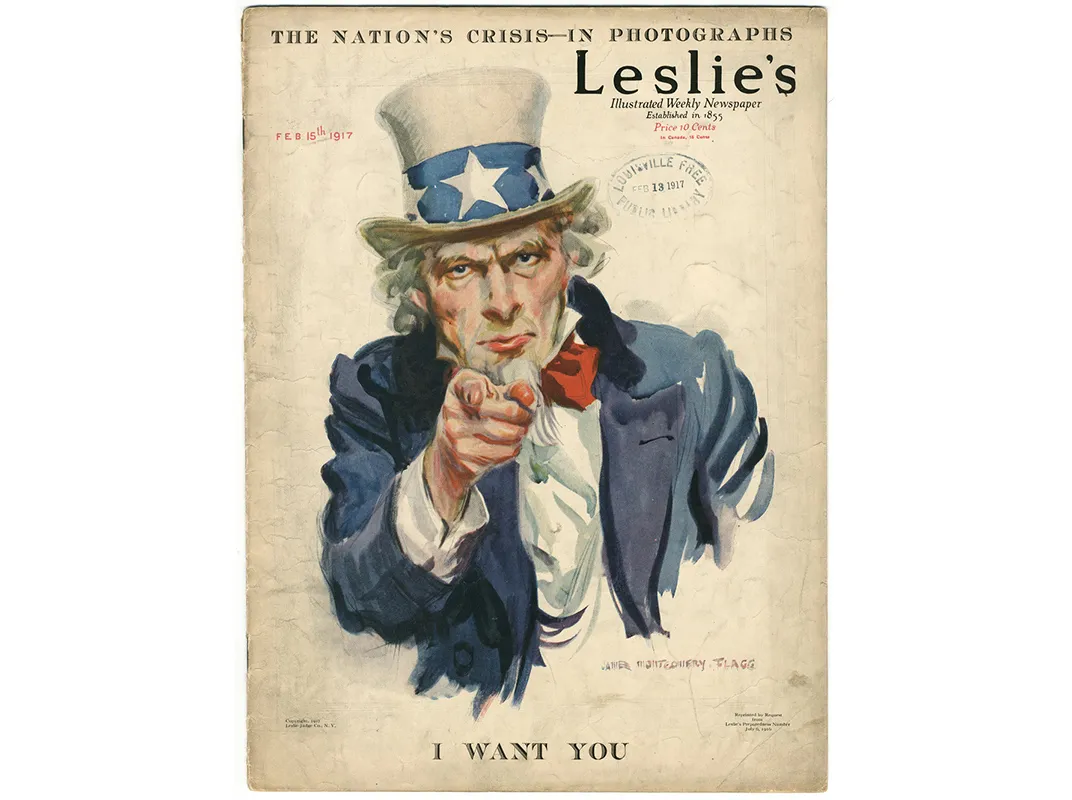

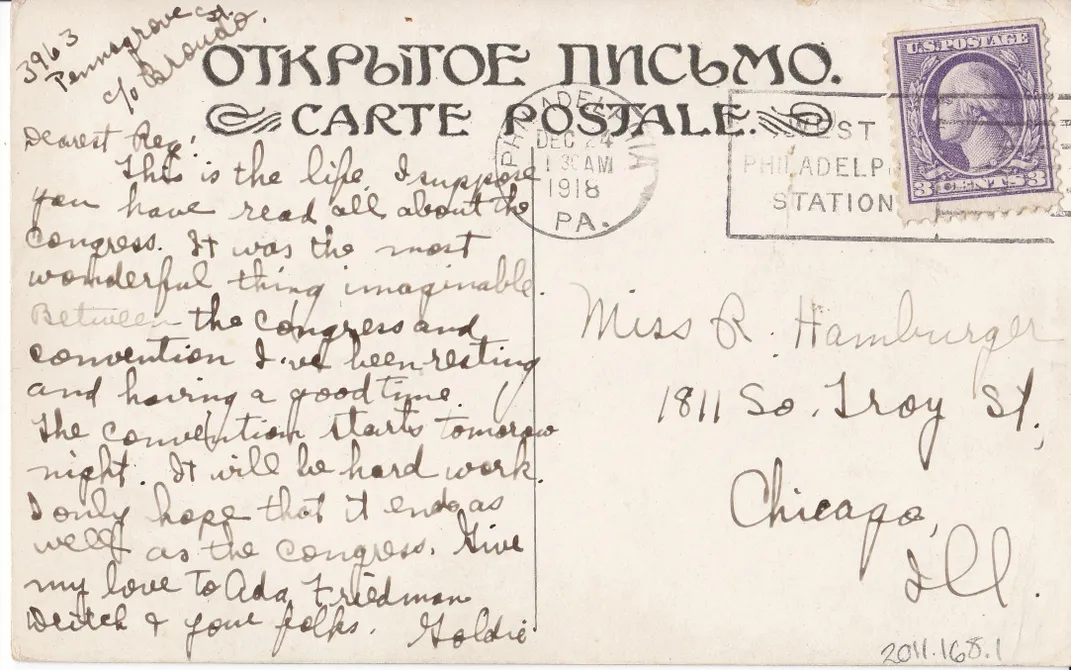

The etchings—one in now-faded pencil on a piece of hotel stationary from the Imperial Hotel in London, the other with pencil and ink edits over blue typewriter text—are never before exhibited versions of the Balfour Declaration, a letter written by British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour in November 1917. Sent by Balfour to a leader of Britain’s Zionists, the text declared British support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The drafts themselves are in the handwriting of prominent British Zionist Leon Simon, who helped to draft the declaration, and are now on public view for the first time in 1917: How One Year Changed the World, a joint exhibition of the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS) in New York City and the National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) in Philadelphia.

“This little paragraph on a piece of paper,” says Rachel Lithgow, director of AJHS in New York, gave “a downtrodden people hope after 2,000 years.”

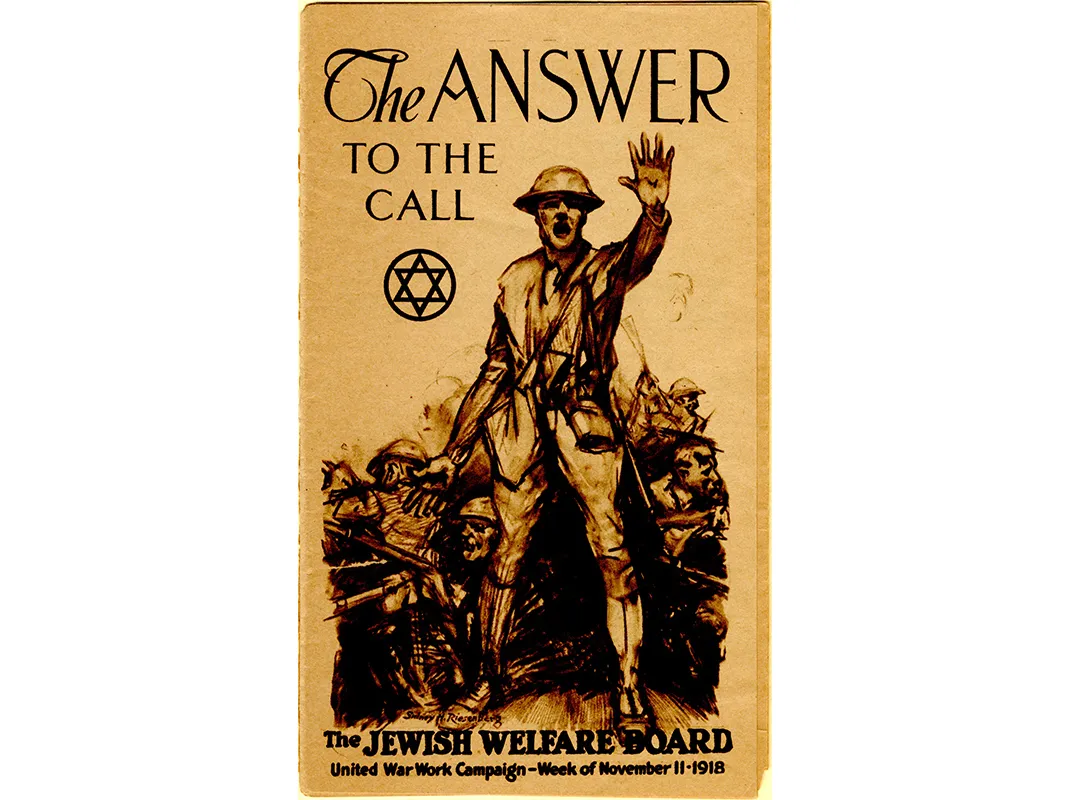

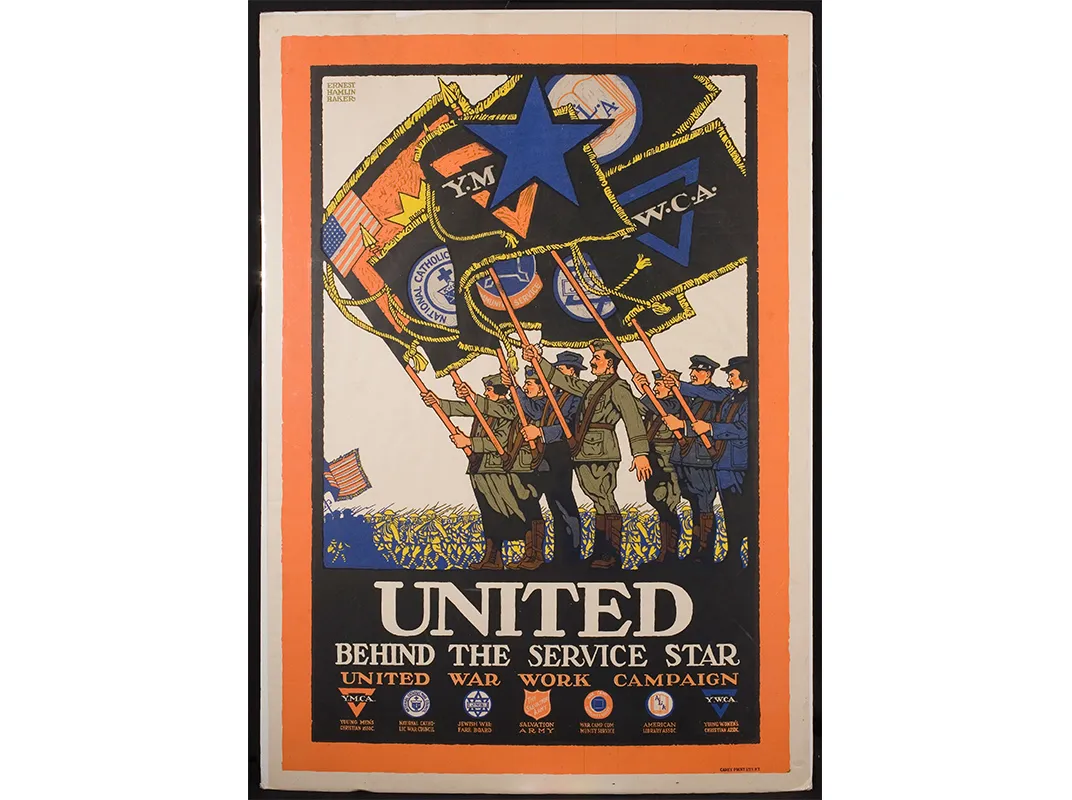

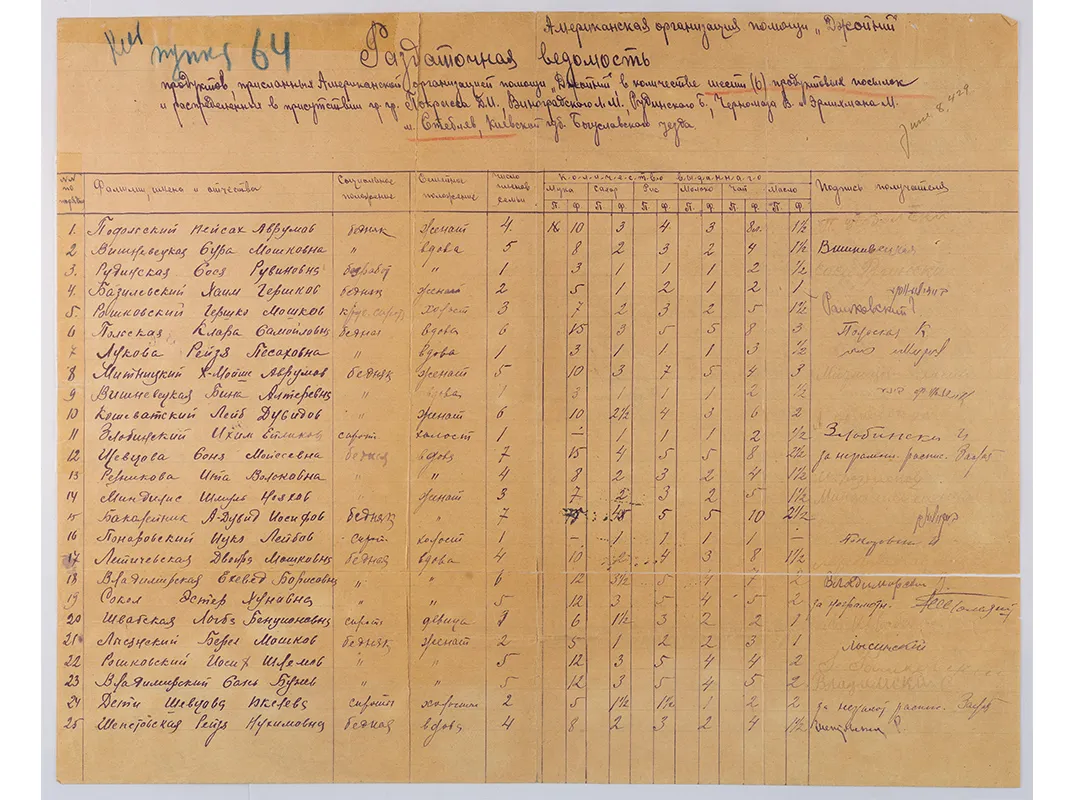

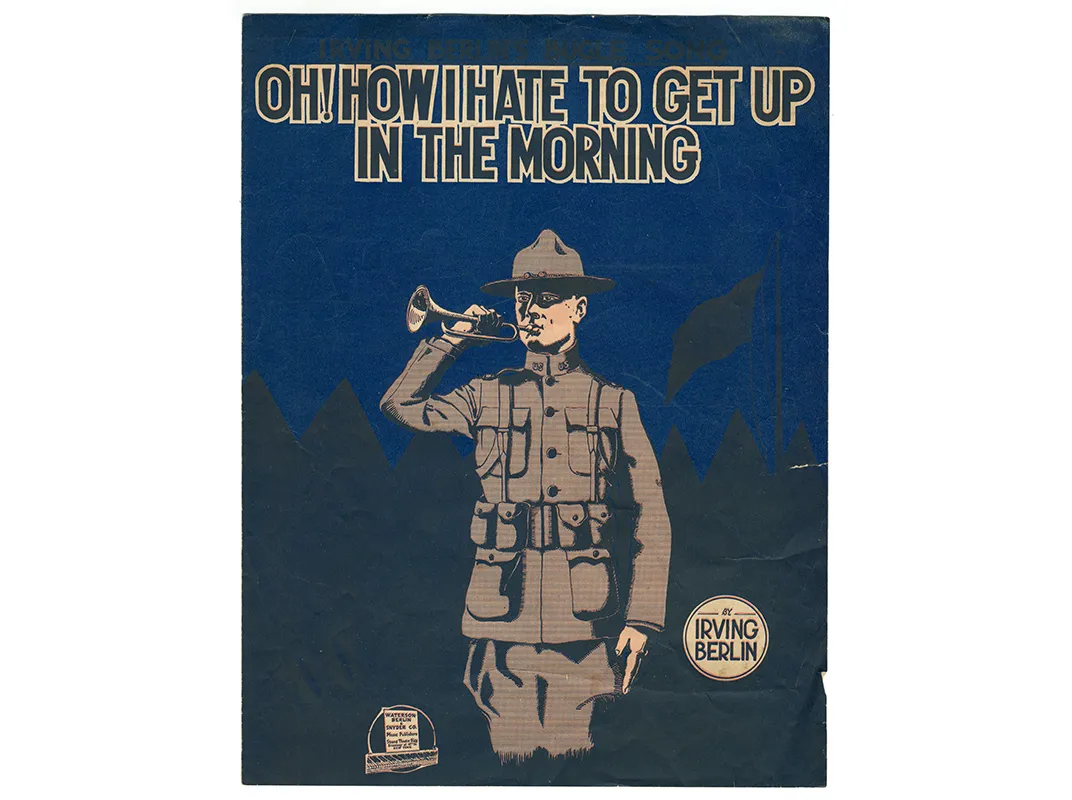

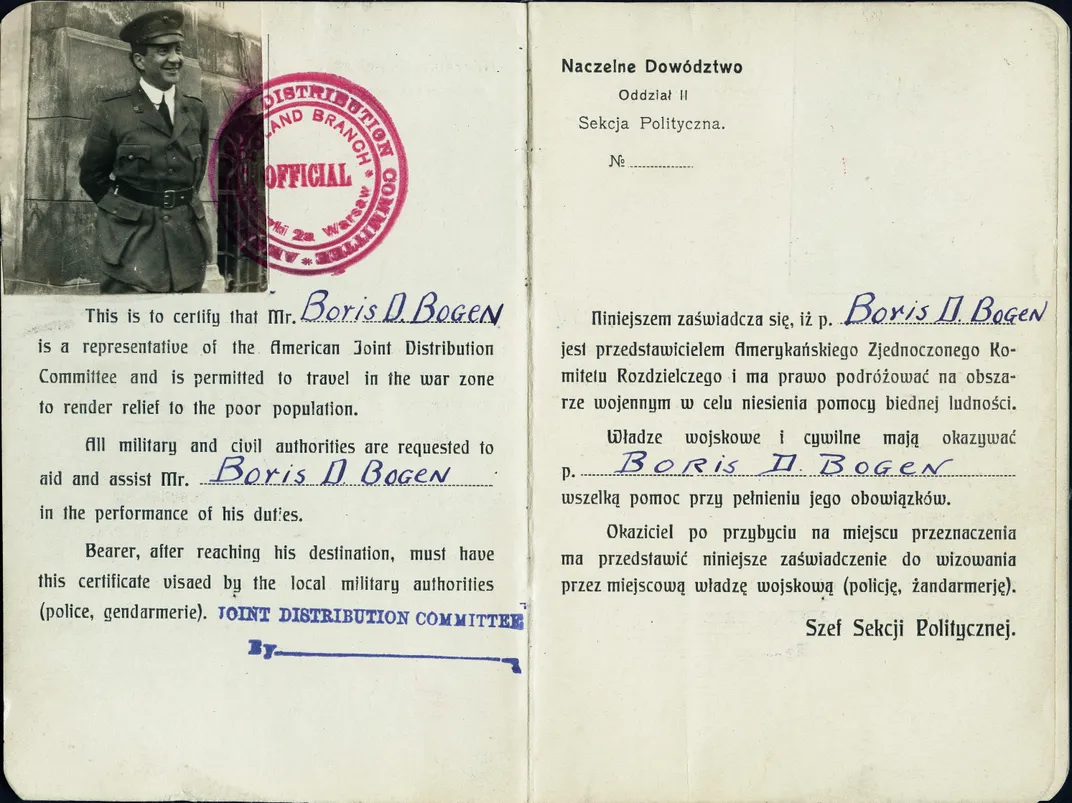

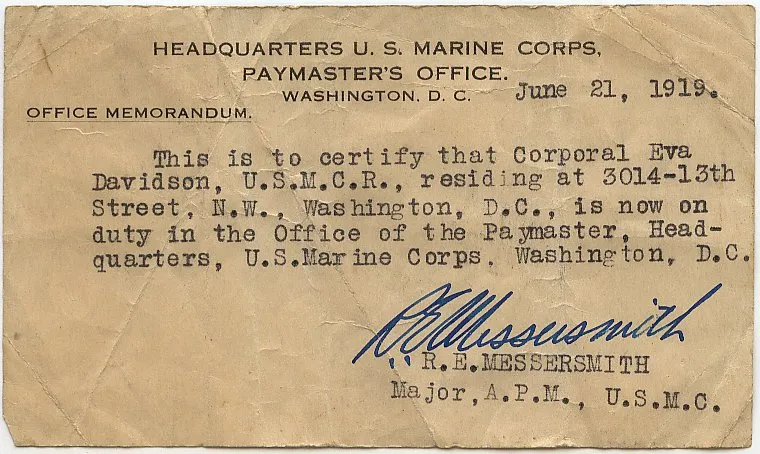

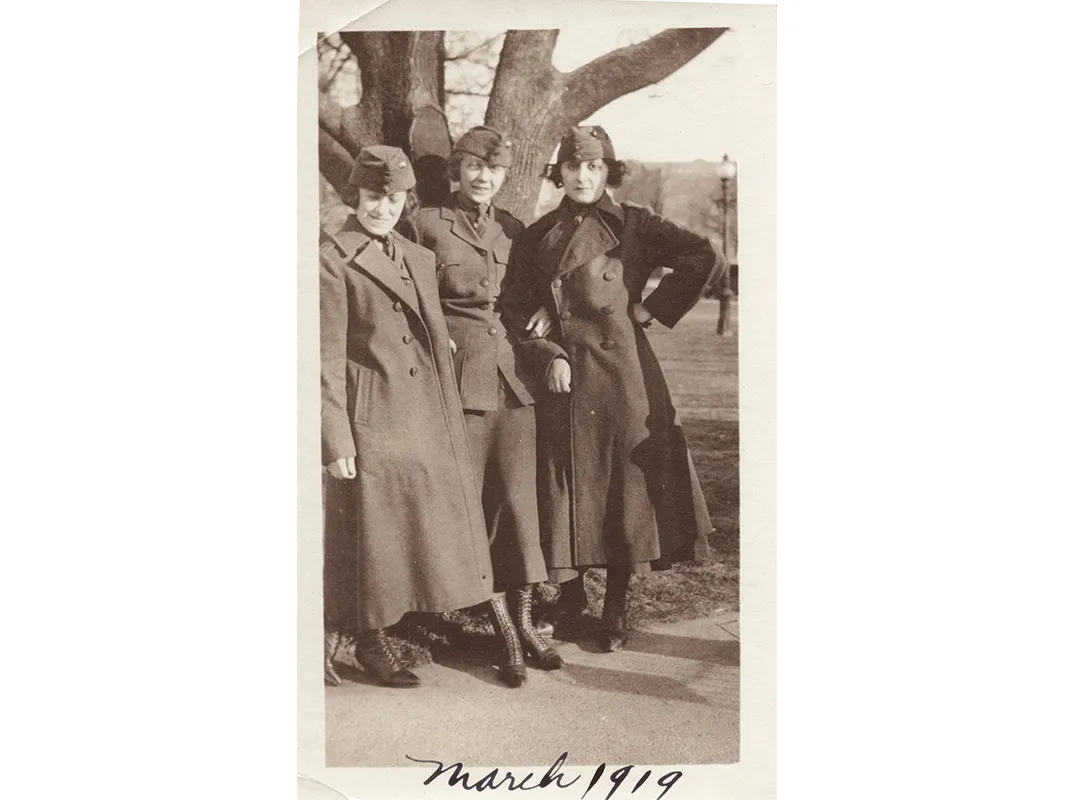

The exhibition, says Josh Perelman, chief curator and director of exhibitions and collections at NMAJH, is the first to show how three key political events of 1917—America’s entry into World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the Balfour Declaration—transformed world events and “reshaped the United States.” Its approximately 125 artifacts are arranged to reflect the American Jewish perspective of international events during the war years, starting with America’s entrance in 1917 and ending with the Johnson Reed Act of 1924, which imposed strict quotas on immigration.

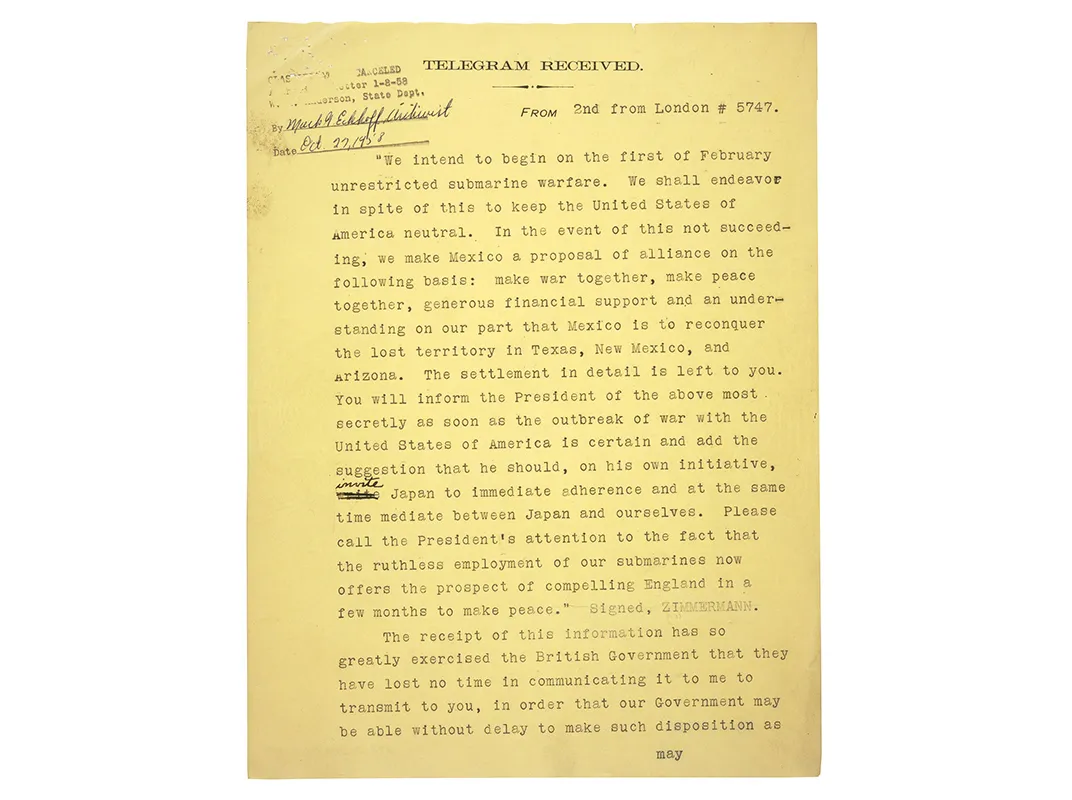

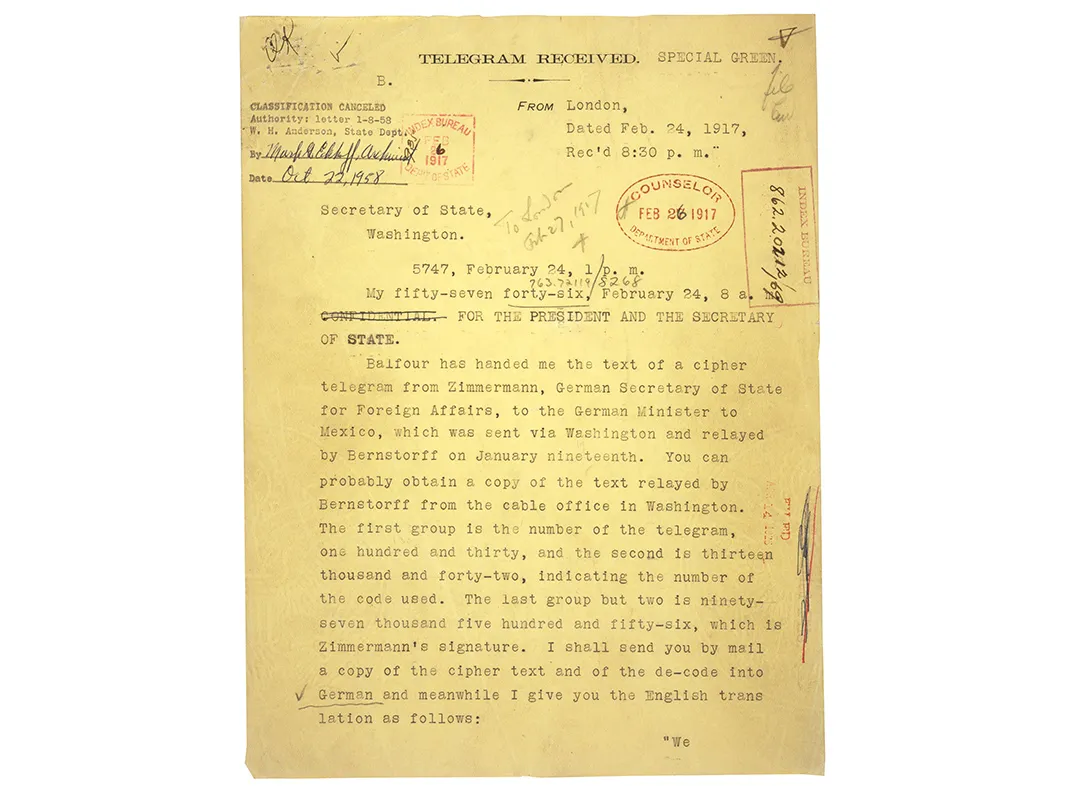

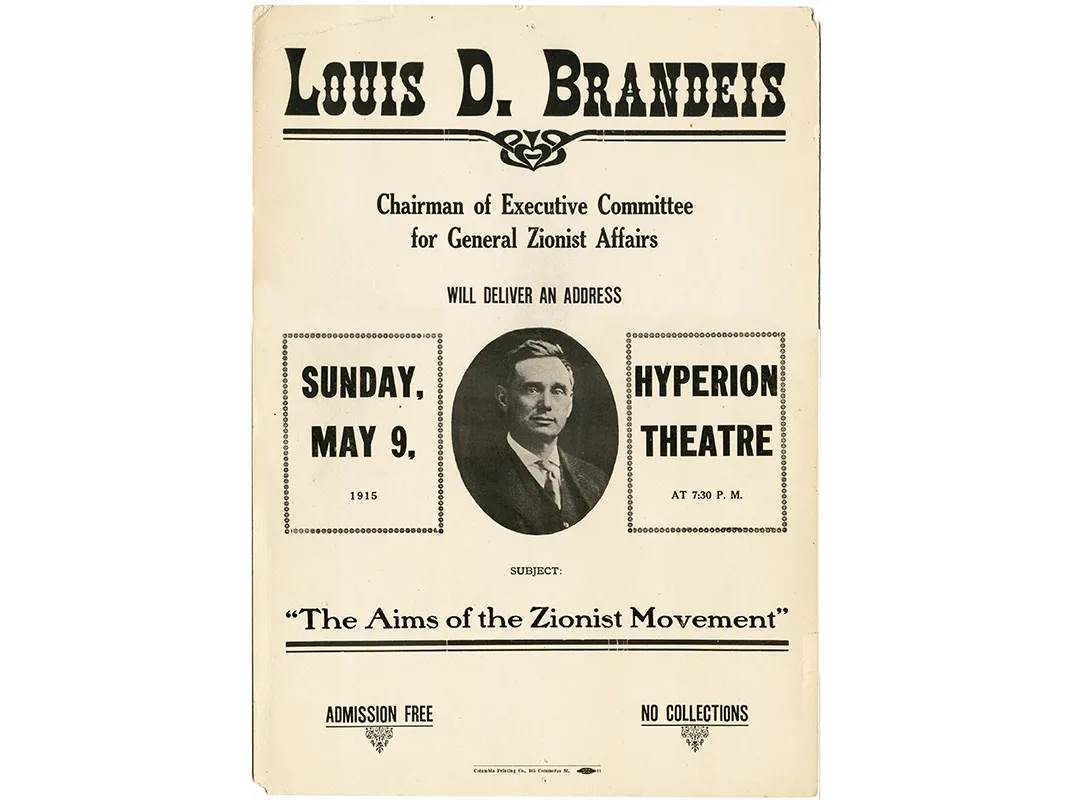

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’s judicial robes, Emma Goldman’s deportation warrant and a decoded copy of the Zimmermann Telegram can all be found within the exhibit, which is on view at the NMAJH through July 16 and at the AJHS from September 1 through December 29. But the exhibition’s most significant artifacts might be the scribbles—precursors to a document that sparked a conflict that still rages today.

Secretary Balfour addressed his finalized letter on November 2, 1917 to prominent Zionist Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild. Heir to the banking family’s empire, Rothschild was also a British politician who had lobbied heavily on behalf of the Jewish cause.

“His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” wrote Balfour, “and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

“Rarely in the annals of the British Empire has such a short comment produced such far-reaching consequences,” writes historian Avi Shlaim. A week after Balfour sent the letter, newspapers published it around the world. Support abroad came swiftly from President Woodrow Wilson, Pope Benedict XV, and Britain’s French, Italian and Serbian allies in the First World War.

Zionist groups celebrated. “With one step the Jewish cause has made a great bound forward,” wrote The Jewish Chronicle in London. “[The Jew] is at last coming to his right….The day of his exile is to be ended.”

Not all Jews agreed. The Central Conference of American Rabbis, the rabbinic organization for the Reform movement in the U.S., issued a resolution stating that there was no need for a “national homeland for the Jewish people.” Instead, they posited, Jews were “at home” wherever they practiced their faith and contributed culturally, socially and economically. “We believe that Israel, the Jewish people, like every other religious communion, has a right to live, to be at home and to assert its principles in every part of the world,” the organization wrote.

Arabs—91 percent of Palestine’s population—protested too. Dr. Joseph Collins, a New York neurologist, professor and travel writer, commented on the ethnic and religious clashes that he witnessed between Arabs and Jews. “Jerusalem is reeking with latent fanaticism, bursting with suppressed religiosity and tingling with repressed racial animosity,” he wrote. “Palestine is destined, if allowed to go on as it is now going, to be the battlefield of the religions.”

Today, Balfour is best remembered for the declaration that carries his name. But at the time, he was more famous for his vaunted political career. Assisted by his prominent political uncle, Lord Salisbury, he rose through the ranks of the Conservative Party for decades; Balfour succeeded Salisbury as Prime Minister from 1902 until 1905, when he resigned his position after rifts over tariff reform weakened the party. In 1906, the Liberal Party took control of the British government for nearly 20 years, and although Balfour led the opposition until 1911, he was later appointed to two cabinet positions: in 1915, he succeeded Winston Churchill as First Lord of Admiralty (head of the British Navy), and in 1917, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George named him Foreign Secretary.

Soon after resigning as Prime Minister in 1905, Balfour, a Christian mystic, discussed Zionism with chemist Chaim Weizmann, a leader of the Zionist Political Committee in Manchester, England (and the future first president of Israel). The Jewish nationalist movement had gained traction in Europe towards the end of the 19th century, largely due to the efforts of Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl. Herzl, who argued that a Jewish national state was the only practical solution to rising European anti-Semitism, established the first Zionist Congress in Switzerland in 1897.

Zionism made sense to people across the political spectrum—from imperialists who thought a Jewish homeland in Palestine would allow for a stronger British presence in the Middle East, particularly along trade routes to India and Egypt, to Christians who believed God’s “chosen people” belonged in Palestine, to anti-Semites who wanted Jews to live in one place. “It was also thought,” writes British historian Avi Shlaim, “that a Declaration favorable to the ideas of Zionism was likely to enlist the support of the Jews of America and Russia for the war effort against Germany.”

Of the 90,000 Jews who had settled in Palestine prior to the war, many were refugees who had fled Russian pogroms. During the war years, Russian Jews who had settled in England – such as Chaim Weizmann -- assumed leadership of the movement. When Balfour was appointed Foreign Secretary in 1917, he was well positioned to advance Zionist hopes.

Soon after taking office, Balfour asked for a statement from Rothschild that would articulate Zionist wishes. Members of the Committee met at the Imperial Hotel in London in July to draft this statement.

One of these writers, a Hebrew scholar named Leon Simon, kept two drafts among his personal papers. In 2005, his manuscript collection, full of autographs, letters, essays and photographs relating to the Manchester Zionists and the beginning of the State of Israel, went to auction at Sotheby’s. “No other monument of the formation of Israel of this magnitude and from this early period has been offered at auction,” read the catalogue note. The collection sold for $884,000 to a private collector. Those two drafts, on loan from the collector, are what are now on view at the museum.

Between July and November 1917, Balfour and the Committee discussed, edited and revised what became the declaration, considering the fragility of its every word. For in advocating a Jewish homeland in Palestine, the British government would be reneging on a pact it had made with Arabs two years before.

During World War I, the British strategized against the Ottomans, who were allied with Imperial Germany, by encouraging an Arab revolt led by the Sharif of Mecca: his people had long desired independence from the Turks. In return, the Sharif thought, the British would support a pan-Arabic kingdom. The Balfour Declaration compromised that communication, confusing and instigating Arab nationalists with the legal status it promised to Zionists as the Ottoman Empire collapsed.

“From the start,” writes Avi Shlaim, “the central problem facing British officials in Palestine was that of reconciling an angry and hostile Arab majority to the implementation of the pro-Zionist policy that was publicly proclaimed on November 2, 1917.”

In 1920, the League of Nations gave Britain a mandate to manage the Jewish homeland in Palestine. It would be no easy task. Arab-Jewish conflict had already begun; fueled by Arab resentment, rioting and violence accompanied the following three decades of British rule. Concerned with Arab demands for immigration control, the British did, at times, restrict Jewish immigration to Palestine: such as in 1936, when the Jewish population there reached 30 percent. The decision of the British government to limit immigration over the next several years trapped many Jews in Nazi Europe.

In 1947, when the British absolved itself of its Palestine mandate, the United Nations General Assembly voted to separate Palestine into two states. On May 14, 1948, the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel was broadcast over the radio. The next day, the Israeli-Arab War of 1948, the first of many regional wars, began.

“The events of 1917 are often overshadowed by other events, direct and deep,” says Josh Perelman of the National Museum of American Jewish History. “By raising awareness of what happened during 1917,” he says, the exhibit informs our understanding of the century yet to come.