When Rhinos Once Roamed in Washington State

Road-tripping through prehistoric times on the West Coast

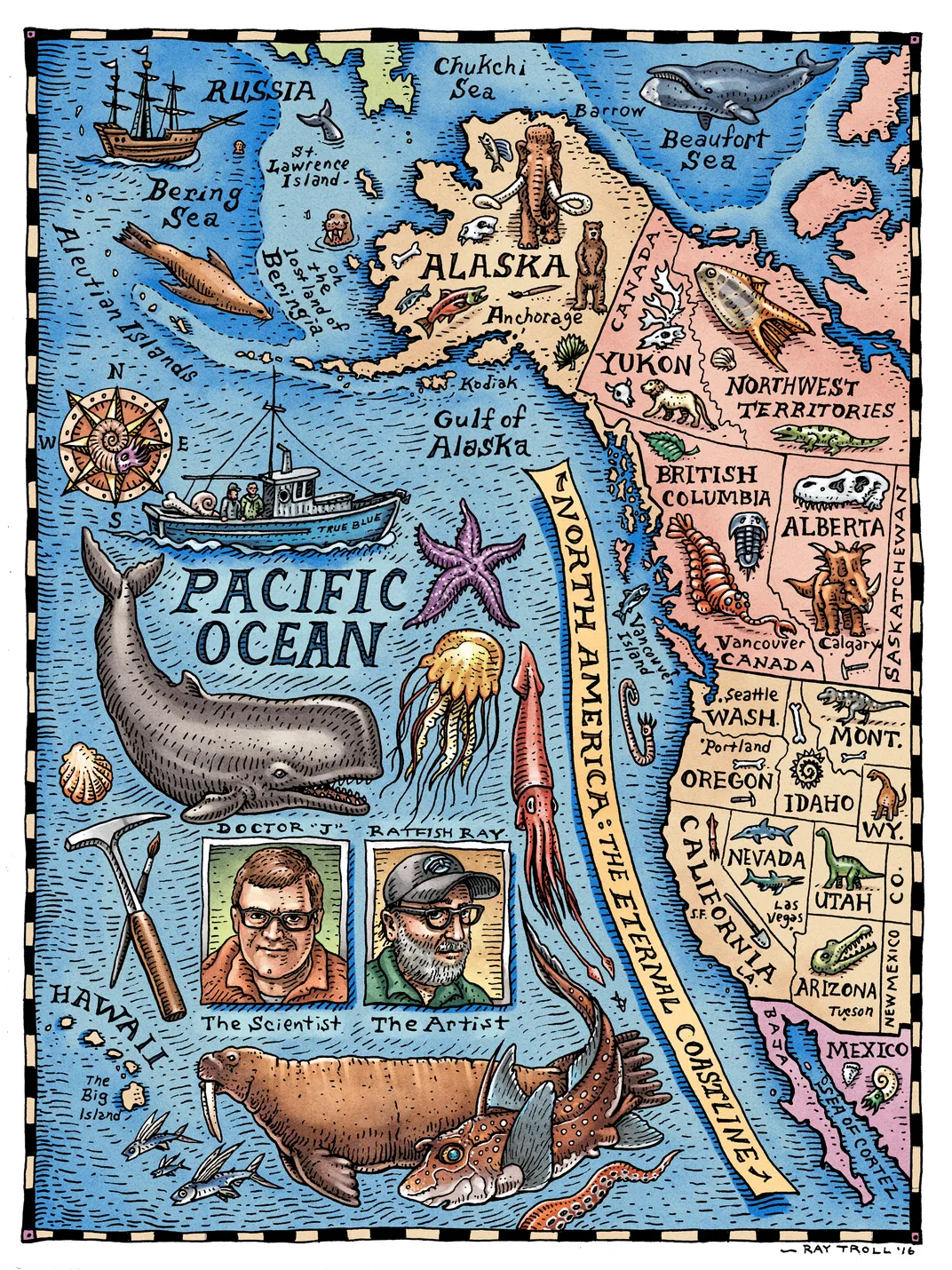

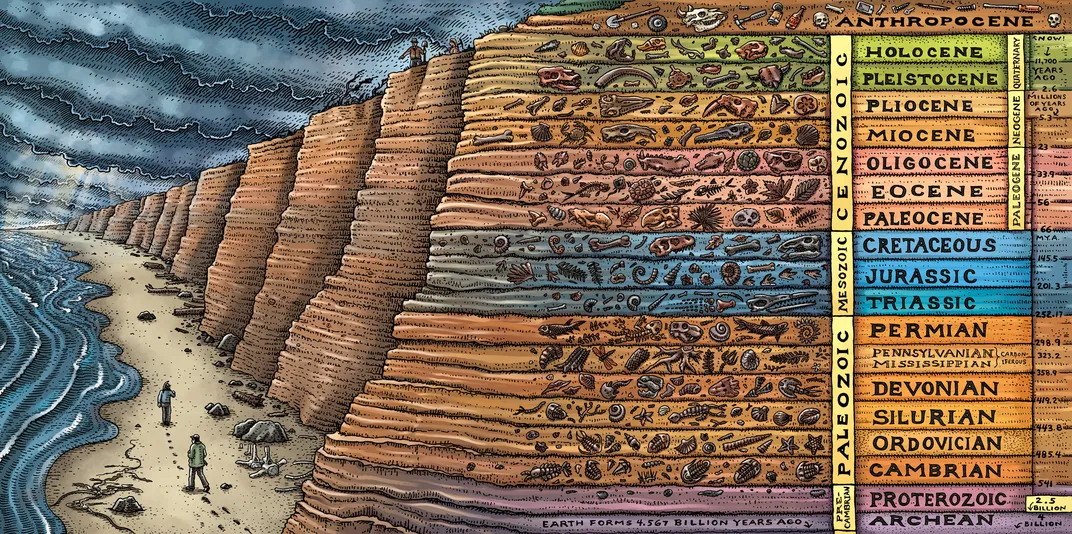

Geologically, the West Coast of North America is one of the oldest coastlines on earth, but its amazing fossils are little known even to local residents. Which is why, over the past ten years, the artist Ray Troll and I went on a series of eye-popping paleontological road trips from Baja California to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska.

To get a feel for one of the oddest fossils on the continent, we pulled over at the north end of Blue Lake in Washington and plunked down $9 to rent a rowboat. Our goal: the legendary Blue Lake Rhino.

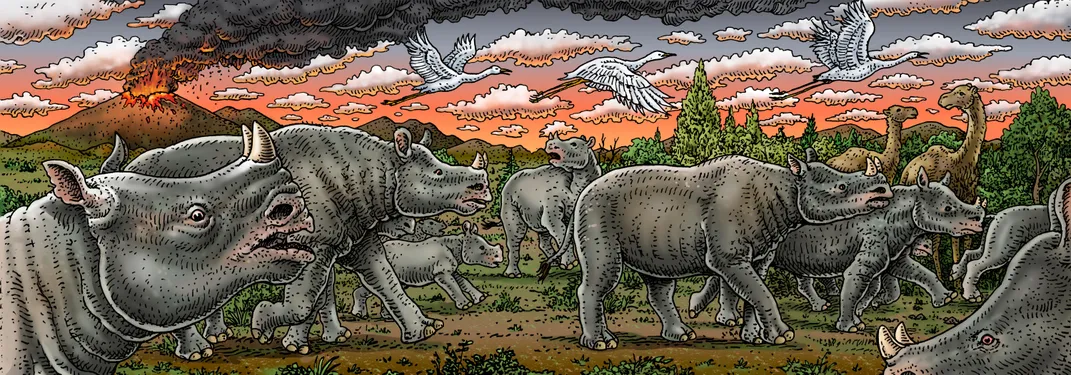

In 1935, two couples, the Frieles and the Peabodys, were poking around the lava cliffs in search of petrified wood when they found a large hole. Haakon Friele crawled in, expecting to find fossil wood. Instead, he found fragments of fossil bone including part of a jaw. Scientists identified the jaw as belonging to a Miocene rhinoceros called Diceratherium, a distant relative of our modern rhinos, first discovered in 1875. In 1948, a University of California, Berkeley crew made a plaster mold of the cavity’s interior. It had the distinctive shape of a large and somewhat bloated four-legged rhinoceros lying on its back. Because the walls of the cavity were pillow basalt, which forms when lava flows into water, the obvious conclusion was that a rhino was in a shallow pool or stream when it was entombed. Eventually, the lava cooled and was buried. Then 15 million years passed, and the Spokane Floods miraculously eroded a hole at the tail end of the beast. The Frieles and the Peabodys found it 13,000 years later.

Now we had arrived to find that same hole on the cliff face. Someone had painted a white “R” about 200 feet up—a very good sign. We scrambled up the steep slope to the base of the cliff. At the top we were confronted with a little zone of treacherous verticality and gingerly made our way to a ledge the width of a narrow sidewalk. We found several small holes that must have once contained petrified logs, but the rhino hole was nowhere to be found. We were stumped.

We were about to give up when we noticed a geocache with a series of notes. Several celebrated the success of their authors in finding the rhino. Others expressed exasperation. Then we read one that said: “Found it! Straight above this cache. Cool.” We looked up and there was the hole. We were elated, and I was just a bit terrified. A nine-foot climb above a narrow ledge above a long drop did not appeal to me. But I had not come this far not to crawl into the rhino’s rump. I love experiencing the most unlikely natural phenomena on our planet and a cave formed by an incinerated rhino surely ranks high on that list. So up and in I went. Nine dollars well spent.

Kirk Johnson chronicled his recent journeys in Cruisn' the Fossil Coastline: The Travels of An Artist and a Scientist Along the Shores of the Pacific, excerpted here. The book is based on travels that Johnson, the director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, completed before he came to Washington, D.C. The book is based on Johnson’s personal, scientific research, and the views and conclusions are expressly his own and do not represent those of the Smithsonian Institution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/fetters_180911_1737x.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/fetters_180911_1737x.jpg)