A New Memorial Remembers the Thousands of African-Americans Who Were Lynched

Next month’s opening of the monument in Alabama will be a necessary step in reckoning with America’s deadly past

In the early months of 1904, a black man named Luther Holbert was accused by neighbors in Doddsville, Mississippi, of killing a white farmer. Holbert was never given a chance to stand trial. Instead, he and an unnamed female companion were chased dozens of miles across Sunflower County before they were captured, tied to a tree, tortured with corkscrews and knives, and burned alive. Although hundreds of people observed the double lynching—according to newspaper reports, the crowd dined on deviled eggs, whiskey and lemonade—no monument was erected to remember the brutally murdered man and woman and no charges were ever brought against their killers.

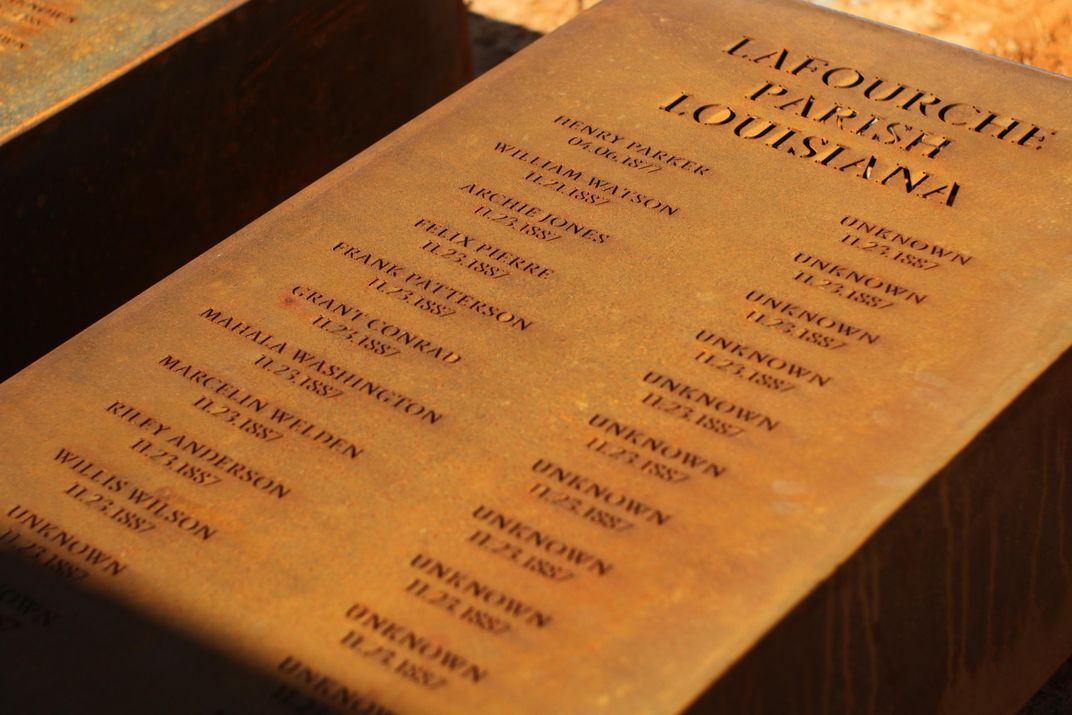

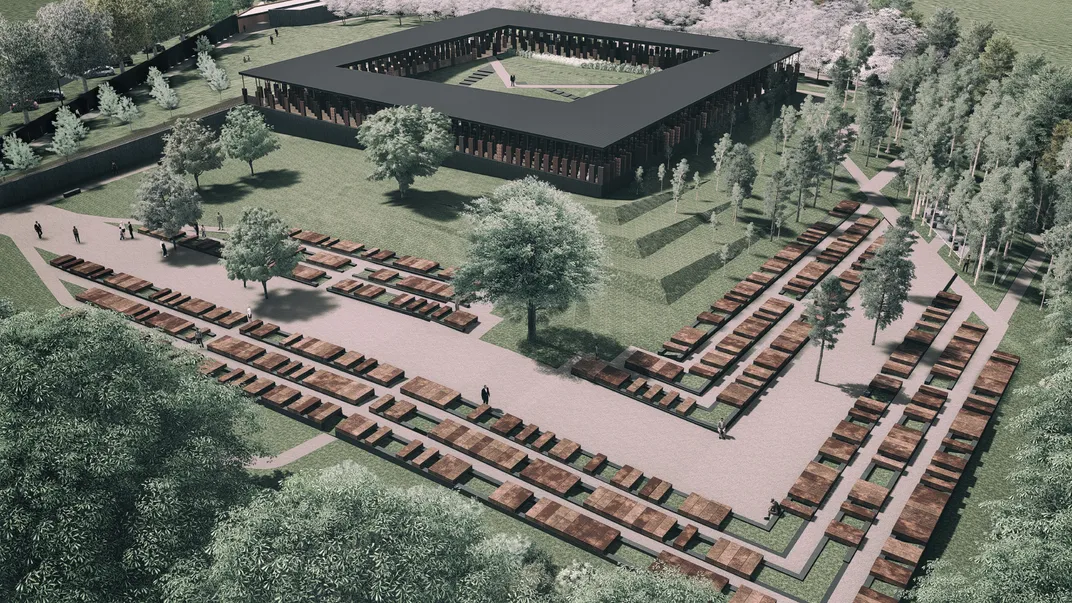

Now Holbert’s name is finally being etched into history—along with those of 4,400 other lynching victims—at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opens next month in Montgomery, Alabama. It’s the first monument to the lynching campaign that terrorized black residents of the South and Midwest for more than 80 years. Created by the Equal Justice Initiative, a legal advocacy group led by the lawyer and author Bryan Stevenson, the memorial sits on a grassy hilltop in the city. Entering the structure, viewers come face to face with 800 rectangular steel slabs, each representing a county where at least one lynching took place. Each slab is about the height of an adult and appears to hang from the ceiling on a metal pipe. Some slabs hold scores of names. Victims who remain unidentified, like Holbert’s companion, are marked “unknown.”

The United States has “failed to tell the truth about slavery, racial terror lynching and the shameful mistreatment of people of color,” says Stevenson (who received a Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award for Social Progress in 2012). “I want our memorial to be a correction, to begin a conversation that is rooted in truth.”

Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror

"Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror" documents EJI's multi-year investigation into lynching in twelve Southern states during the period between Reconstruction and World War II.

The hope is that the conversation will reach far beyond Montgomery, says staff attorney Jennifer Taylor. In addition to the permanent slabs inside the memorial, an identical set of slabs will be placed outside it, to be claimed by the named counties and erected back home. The design challenges people in places where lynchings occurred to acknowledge that history; over time, it will become apparent at the Montgomery site which counties choose to memorialize lynching victims by retrieving a marker, and which counties prefer not to.

“We need truth and reconciliation in America, but I believe that process is sequential,” says Stevenson. “We must first tell the truth before we can frame a response that heals and repairs the damage of racial injustice.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.