The Sordid History of Mount Rushmore

The sculptor behind the American landmark had some unseemly ties to white supremacy groups

:focal(4346x2831:4347x2832)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/31/0431eeef-c000-4d83-9999-a612ae08c451/oct2016_l09_phenom.jpg)

Each year, two million visitors walk or roll from the entrance of Mount Rushmore National Memorial, in South Dakota, to the Avenue of Flags, to peer up at the 60-foot visages of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt. Dedicated 75 years ago this month, Mount Rushmore was intended by its creator, Gutzon Borglum, to be a celebration of not only these four presidents but also the nation’s unprecedented greatness. “This colossus is our mark,” he wrote with typical bombast. Yet Borglum’s own sordid story shows that this beloved site is also a testament to the ego and ugly ambition that undergird even our best-known triumphs.

In 1914, Borglum was a sculptor in Connecticut of modest acclaim when he received an inquiry from the elderly president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, C. Helen Plane, about building a “shrine to the South” near Atlanta. When he first glimpsed “the virgin stone” of his canvas, a quartz hump called Stone Mountain, Borglum later recalled, “I saw the thing I had been dreaming of all my life.” He sketched out a vast sculpture of generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and was hired.

The son of polygamist Mormons from Idaho, Borglum had no ties to the Confederacy, but he had white supremacist leanings. In letters he fretted about a “mongrel horde” overrunning the “Nordic” purity of the West, and once said, “I would not trust an Indian, off-hand, 9 out of 10, where I would not trust a white man 1 out of 10.” Above all, he was an opportunist. He aligned himself with the Ku Klux Klan, an organization reborn—it had faded after the Civil War—in a torch-light ceremony atop Stone Mountain in 1915. While there isn’t proof that Borglum officially joined the Klan, which helped fund the project, “he nonetheless became deeply involved in Klan politics,” John Taliaferro writes in Great White Fathers, his 2002 history of Mount Rushmore.

Borglum’s decision to work with the Klan wasn’t even a sound business proposition. By the mid-1920s, infighting left the group in disarray and fundraising for the Stone Mountain memorial stalled. Around then, the South Dakota historian behind the Mount Rushmore initiative approached Borglum—an overture that enraged Borglum’s Atlanta backers, who fired him on February 25, 1925. He took an ax to his models for the shrine, and with a posse of locals on his heels, fled to North Carolina.

Related Read: Great White Fathers

The true story of Gutzon Borglum and his obsessive quest to create the Mount Rushmore national monument

The Stone Mountain sponsors sandblasted Borglum’s work and hired a new artist, Henry Augustus Lukeman, to execute the memorial, only adding to Borglum’s bitterness. “Every able man in America refused it, and thank God, every Christian,” Borglum later said of Lukeman. “They got a Jew.” (A third sculptor, Walker Kirtland Hancock, completed the memorial in 1972.)

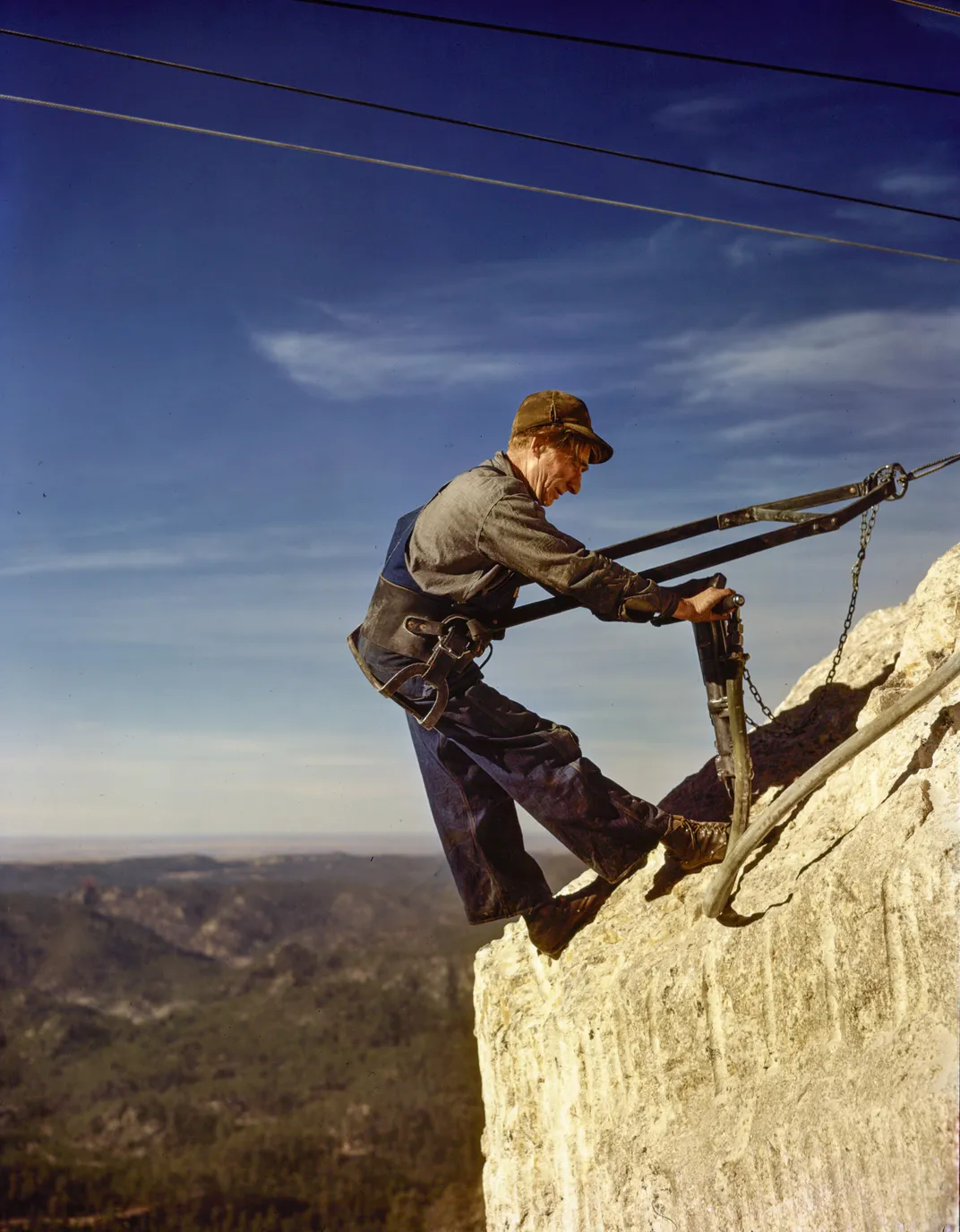

Still, the years in Georgia had given Borglum the expertise to tackle Rushmore, and he began carving in 1927 at age 60. He famously devoted the last 14 years of his life to the project. His son, Lincoln, oversaw the finishing touches.

From supporting the Klan to memorializing Lincoln: What are we to make of that trajectory? Anyone who creates an immensely popular sculpture by dynamiting 450,000 tons of stone from the Black Hills deserves recognition. Taliaferro says we like to think of America as the land of the self-made success, but the “flip side of that coin,” he says, “is that it’s our very selfishness—enlightened, perhaps, but primal in its drive for self-advancement—that is the building block of our red-white-and-blue civilization.” And no one represents that paradox better than Gutzon Borglum.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/6c/d46c876f-da51-469f-9a74-619909149ebf/oct2016_l05_phenom.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/29/57295615-4f2e-4830-b2ce-b5f687e85af6/oct2016_l07_phenom.jpg)