Travel to Southern France for a Dazzling Taste of Ancient Rome

A new museum in Nimes pays tribute to the grandeur of the Empire

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/82/b3825632-5612-45e2-924f-554067096822/jun2018_b23_prologue-wr.jpg)

"In NÎmes, when you dig, you find," says Daniel-Jean Valade. He’s in charge of cultural affairs for the southern French city, which was established in the first century as a kind of billboard for Roman life in Gaul. Today, modern Nîmes lives alongside ancient Rome and the two keep bumping into each other, both above ground and below.

When the remains of a grand Roman villa were unearthed during construction work for a parking garage, in 2006, the city was finally convinced that its old museum was sadly inadequate for the active archaeological dig that is Nîmes. The upshot is the just-opened Musée de la Romanité, which means something like “Romanosity,” the gestalt of what life in an old Roman town must have felt like.

Archaeology Hotspot France: Unearthing the Past for Armchair Archaeologists (Volume 3) (Archaeology Hotspots, 3)

In "Archaeology Hotspot France," Georgina Muskett provides insight into the vibrant and varied collection of archaeological sites and monuments in France.

On display for the first time are some of the things that keep sprouting from the local soil. The museum is home to the world’s largest collection of tomb inscriptions, many with enough detail to serve as mini-biographies of Nîmes’ original Roman citizens. Then there’s the huge assortment of glassware, which functions as a lexicon of Roman design.

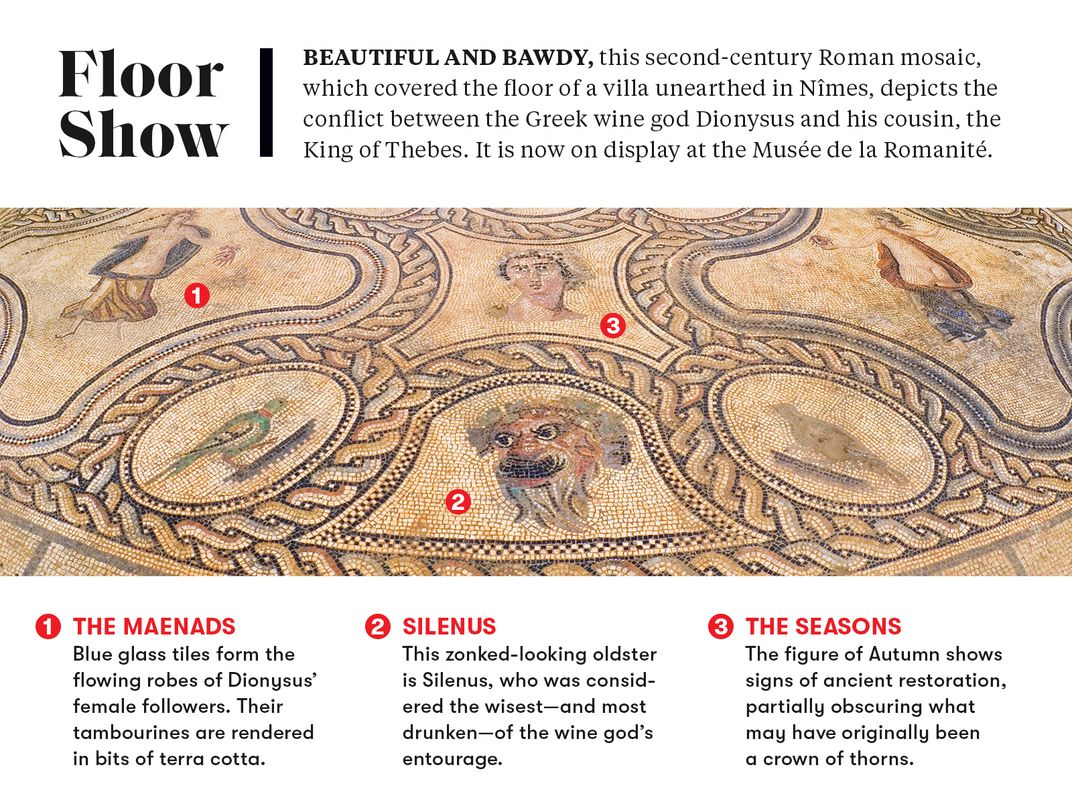

The museum was literally built around a restored portion of the massive pediment that once marked the entrance to the city’s sacred spring, but pride of place goes to an exquisite mosaic masterpiece found on the floor of the rediscovered villa. All across its 375 square feet swarm birds, masks and maenads—the besotted followers of the god Dionysus. In the center, the Theban king Pentheus gets the coup de grâce for snubbing the wine-god’s cult.

The museum’s architect, Elizabeth de Portzamparc, conceived the building as a stylistic give-and-take across the centuries with its next-door neighbor, the 20,000-seat Arènes de Nîmes, a Roman-era stadium still used for bullfights and concerts. “On the one hand, you have a round space surrounded by vertical Roman arches in stone and anchored to the ground, and on the other, a big square space, floating and draped in a toga of folded glass,” says de Portzamparc.

Of course, the new museum is designed to attract tourists; the ancient arena already gets some 350,000 visitors every year. But the museum also hopes to play a part in the lives of residents. A recreated Roman street in the museum’s garden serves as a public thoroughfare, another daily reminder of the city’s rich history.

“On any given day, you can see a group of school kids sitting in the shade of the Maison Carrée eating their McDonald’s,” says Valade of a beautiful little temple that the Roman emperor Augustus built for his two grandsons. “The people most concerned by their Roman patrimony are the people who live here. I know Nîmes since I’m 7 or 8 months old,” adds Valade, who was born nearby. “Like Romulus or Remus, I too was suckled by the Roman she-wolf.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.