Sparta Was Much More Than an Army of Super Warriors

Fierce? Yes. Tough? You bet. But the true history of the Greek civilization had a lot more nuance

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2f/52/2f52b3c8-c8da-4159-8c28-a37da7dff5ac/oct2021_e19_prologue.jpg)

Ancient Sparta has been held up for the last two and a half millennia as the unmatched warrior city-state, where every male was raised from infancy to fight to the death. This view, as ingrained as it is alluring, is almost entirely false.

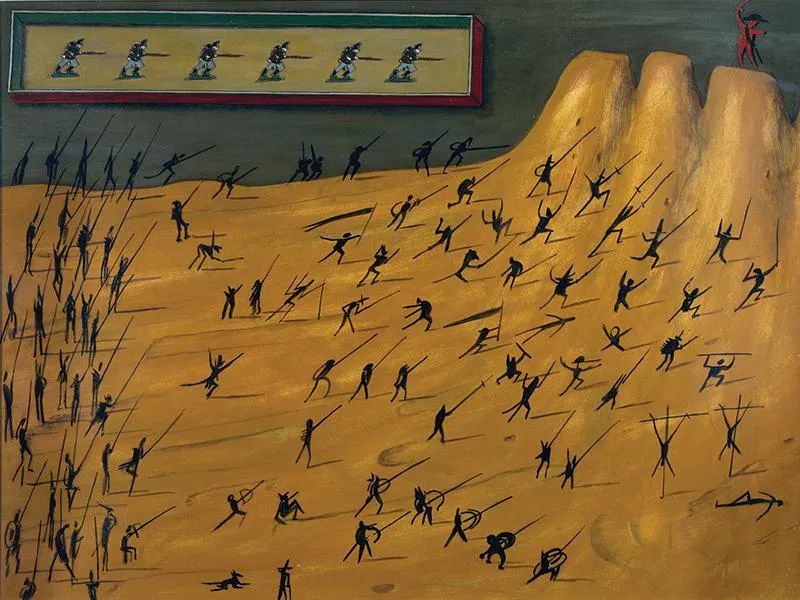

The myth of Sparta’s martial prowess owes much of its power to a storied feat of heroism accomplished by Leonidas, king of Sparta and hero of the celebrated Battle of Thermopylae (480 B.C.). In the battle, the Persian Army crushed more than 7,000 Greeks—including 300 Spartans, who are widely and falsely believed to have been the only Greeks fighting in that battle—and went on to capture and burn Athens. Outflanked and hopelessly outnumbered, Leonidas and his men fought to the death, epitomizing Herodotus’ pronouncement that all Spartan soldiers would “abide at their posts and there conquer or die.” This singular episode of self-sacrificing bravery has long obscured our understanding of the real Sparta.

Actually, Spartans could be as cowardly and corrupt, as likely to surrender or flee, as any other ancient Greeks. The super-warrior myth—most recently bolstered in the special effects extravaganza 300, a movie in which Leonidas, 60 at the time of the battle, was portrayed as a hunky 36—blinds us to the real ancient Spartans. They were fallible men of flesh and bone whose biographies offer important lessons for modern people about heroism and military cunning as well as all-too-human blundering.

There is King Agis II, who bungled various maneuvers against the forces of Argos, Athens and Mantinea at the Battle of Mantinea (418 B.C.) but still managed to pull off a victory. There is the famous Admiral Lysander, whose glorious military career ended with a rash decision to rush into battle against Thebes, probably to deny glory to a domestic rival—a move that cost him his life at the Battle of Haliartus (395 B.C.). There is Callicratidas, whose pragmatism secured critical funding for the Spartan Navy in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.), but who foolishly ordered his ship to ram the Athenians’ during the Battle of Arginusae (406 B.C.), a move that saw him killed. Perhaps the clearest rebuttal of the super-warrior myth is found in the 120 elite Spartans who fought at the Battle of Sphacteria (425 B.C.); when their Athenian enemies surrounded them, they opted to surrender rather than “conquer or die.”

These Spartans, not particularly better or worse than any other ancient warriors, are just a handful of many examples that paint the real, and utterly average, picture of Spartan arms.

But it is this human reality that makes the actual Spartan warrior relatable, even sympathetic, in a way Leonidas can never be. Take the mostly forgotten general, Brasidas, who, instead of embracing death on the battlefield, was careful to survive and learn from his mistakes. Homer may have hailed Odysseus as the cleverest of the Greeks, but Brasidas was a close second.

Almost no one has heard of Brasidas. He’s not a figure immortalized in Hollywood to prop up fantasies, but a human being whose mistakes form a much more instructive arc.

He burst onto the scene in 425 B.C. during Sparta’s struggle against Athens in the Peloponnesian War, breaking through a large cordon with just 100 men to relieve the beleaguered city of Methone (modern Methoni) in southwest Greece. These heroics might have put him on track for mythic fame, but his next campaign would make that prospect far more complicated.

Storming the beach at Pylos that same year, Brasidas ordered his ship to wreck itself on the rocks so he could assault the Athenians. He then barreled down the gangplank straight into the teeth of the enemy.

It was incredibly brave. It was also incredibly stupid.

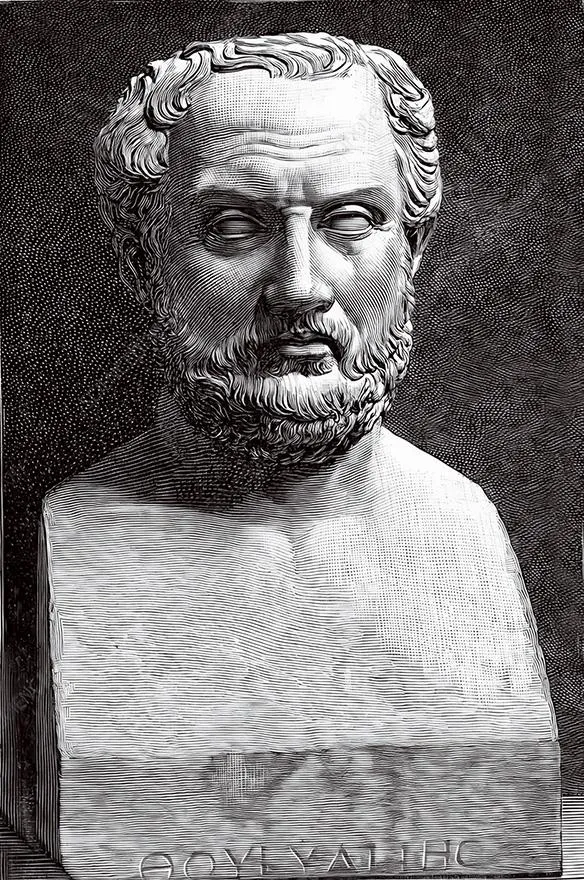

Charging packed troops, Brasidas went down in a storm of missiles before he’d made it three feet. Thucydides tells us that Brasidas “received many wounds, fainted; and falling back into the ship, his shield tumbled into the sea.” Many of us are familiar with the famous admonition of a Spartan mother to her son: “Come back with your shield or on it.” While this line is almost certainly apocryphal, losing one’s shield was nevertheless a signal dishonor. One might expect a Spartan warrior who had both lost his shield and fainted in battle to prefer death to dishonor. That’s certainly the kind of choice Leonidas is celebrated for supposedly making.

Herodotus tells us the two Spartan survivors of Thermopylae received such scorn from their city-state for having lived through a defeat that they took their own lives. But Brasidas, though surely shamed by his survival, did not commit suicide. Instead, he learned.

The following year, we see a recovered Brasidas marching north to conquer Athenian-allied cities at the head of 700 helots, members of Sparta’s reviled slave-caste, who the Spartans constantly feared would revolt. Forming this army of Brasideioi (“Brasidas’ men”) was an innovative idea, and quite possibly a dangerous one. As a solution to the city’s manpower crisis, Sparta had promised them freedom in exchange for military service. And arming and training slaves always threatened to backfire on the slavers.

This revolutionary move was matched by a revolution in Brasidas’ own personality. Far from rushing in, as he once had done, he now captured city after city from the Athenians through cunning—and without a single battle. Thucydides writes that Brasidas, “by showing himself...just and moderate toward the cities, caused most of them to revolt; and some of them he took by treason.” Brasidas let the slaves and citizens of Athenian-held cities do the dirty work for him. After one particularly tense standoff, he won the central Greek city of Megara to Sparta’s cause, then marched north, cleverly outmaneuvering the Athenian-allied Thessalians deliberately to avoid combat.

Arriving at his destination in northeastern Greece, he used diplomacy, threats, showmanship and outright lies to convince the city of Akanthos to revolt from Athens and join Sparta, deftly playing on their fear of losing a harvest that had not yet been gathered. The nearby city of Stagiros came over immediately after.

But his greatest prize was Amphipolis (modern Amfipoli), a powerful city that controlled the critical crossing of the Strymon River (the modern Struma, stretching from northern Greece into Bulgaria). Launching a surprise attack, he put the city under siege—and then offered concessions that were shocking by the standards of the ancient world: free passage for any who wished to leave and a promise not to pillage the wealth of any who remained.

This incredibly risky move could have tarnished Brasidas’ reputation, making him look weak. It certainly runs counter to the myth of the Spartan super-warrior who scoffed at soft power and prized victory in battle above all else.

But it worked. The city came over to Sparta, and the refugees who fled under Brasidas’ offer of free passage took shelter with Thucydides himself in the nearby city of Eion.

Thucydides describes what happened next: “The cities subject to the Athenians, hearing of the capture of Amphipolis, and what assurance [Brasidas] brought with him, and of his gentleness besides, strongly desired innovation, and sent messengers privately inviting him to come.”

Three more cities came over to Sparta. Brasidas then took Torone (modern Toroni, just south of Thessaloniki) with the help of pro-Spartan traitors who opened the city gates for him.

The mythic Leonidas, failing in battle, consigned himself to death. The very real Brasidas, failing in battle, licked his wounds and tried something different. Charging down the gangplank at Pylos had earned him a face full of javelins. He had been lucky to survive, and the lesson he took from the experience was clear: Battle is uncertain, and bravery a mixed commodity at best. War is, at its heart, not a stage for glory but a means to advance policy and impose one’s will. Brasidas had even discovered that victory could be accomplished best without fighting.

Brasidas would make many more mistakes in his campaigns, including the one that would cost him his life outside Amphipolis, where he successfully fought off the Athenians’ attempt to recapture the greatest triumph of his career. Brasidas daringly took advantage of the enemy’s bungled retreat, attacking them and turning their withdrawal into a rout, but at the cost of his life. His funeral was held inside Amphipolis, where today you can visit his funeral box in the archaeological museum.

That he died after renouncing the caution that had marked most of his career seems fitting, a human end for a man who is the best example of the sympathetic fallibility of his city-state’s true military tradition. He is valuable to historians not just for his individual story, but moreover because he illustrates the humanity of real Spartan warriors, in direct contrast to their overblown legend.

Fallible human beings who learn from their errors can achieve great things, and that is the most inspiring lesson the true history of Sparta can teach us.

When we choose a myth over reality, we commit two crimes. The first is against the past, for truth matters. But the second, more egregious, is against ourselves: Denied the chance to see how Spartans struggled and failed and recovered and overcame, we forget that, if they did it, then maybe we can too.