When Althea Gibson stepped onto the patio of the iconic clubhouse at the West Side Tennis Club in 1950, a pair of tennis rackets clasped tightly to her chest, she had arrived at the venerated mecca of tennis in America. Here, at this exclusive, whites-only, members-only retreat in Forest Hills, Queens, the a 23-year-old from Harlem was to become the first African American to compete in the U.S. National Championships, known today as the U.S. Open. Before her lay acres of green velvet grass courts, the playground of many tennis champions. On the flagstone patio, shaded by trim blue-and-yellow awnings, members sipped frosted Rumba cocktails as the nation’s most prestigious tournament got underway.

It was a place that, like many other public and private venues, denied Black people access. That changed when Gibson boldly strode onto the court.

Her barrier-breaking appearance at the West Side Tennis club foretold her legendary career, which over the next decade would grow to include 11 Grand Slam victories.

But in 1950, lest there be any doubt that the organizers of the competition considered Gibson inferior, United States Lawn Tennis Association officials had dispatched her to Court No. 14, a remote court used largely for practice matches, never mind that her presence at the event and her physical appearance—with short hair and white tennis attire against her brown skin—generated much interest. Headlines often described as the “Harlem Negro Girl.”

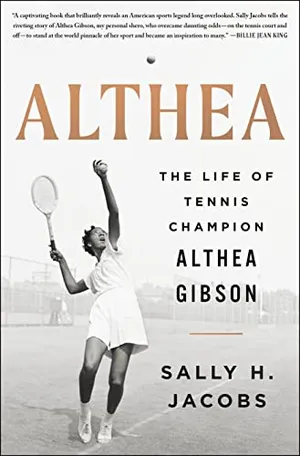

Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson

Prize-winning former Boston Globe reporter Sally H. Jacobs tells the heart-rending story of this pioneer, a remarkable woman who was a trailblazer, a champion, and one of the most remarkable Americans of the twentieth century.

Steeling herself before the explosion of flashbulbs that greeted her, a nervous Gibson headed to the distant court where she was to play what was the most significant match of her career to date. As reporter Lester Rodney of The Daily Worker put it, “No Negro player, man or woman, has ever set foot on one of these courts. In many ways, it is even a tougher personal Jim Crow-busting assignment than was Jackie Robinson’s when he first stepped out of the Brooklyn Dodgers dugout. It’s always tougher for a woman.”

Some members of the press believed that the club managers, whom Milton Gross of the New York Post dubbed “the staid and starchy puffballs running the tennis championships,” had deliberately slighted Gibson. Not only had she been assigned a court with limited seating, but news photographers were also permitted to shoot their flashes off throughout the match, a violation of club tradition, potentially distracting Gibson and her opponent in the critical opening points.

“The excuse for all this is that Althea’s historic appearance was virtually secreted on Court 14, as inaccessible a court as possible on which to stage her debut,” Gross wrote. “While this seems a legitimate enough reason for allowing photogs to do what they are never allowed to do, say, in the stadium court, it is also a reflection of the persistent myopia with which the people who run tennis seem to be afflicted.”

Gibson paid little mind to either the journalists or the burgeoning crowd. Matched against British player Barbara Knapp, Gibson took an offensive tack from the start and never backed off. Her face expressionless, as it often was in competition, she deployed her trademark overhead smash and relentlessly rushed to the net in an easy 6-2, 6-2 victory. Exhilarated, Gibson took the subway back to the city, where she tried to rest in anticipation of her next match the following day. She rose the next morning to find a photograph of herself dominating the New York Times coverage of the event.

If the draw had gone in Gibson’s favor in the first round, it decidedly did not in the second. Her next opponent was America’s No. 2 woman player, veteran Louise Brough, three-time Wimbledon champion and winner of the 1947 U.S. National Championships. Four years older than Gibson, Brough was by far one of the most dominant female players of the day and was enjoying a particularly good year, which she had launched with a win in the women’s singles at the Australian Championships (now the Australian Open). An earnest competitor, Brough was known for her aggressive style and an acclaimed twist serve with topspin that often overwhelmed her opponents, especially on their backhand returns. Also known for her crisp, no-nonsense demeanor and humorless expression, Brough was seen by many of the younger women on the circuit as a formidable figure best to be avoided off court.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/20/7020b698-77d0-43da-a4aa-5bd1113f9fad/althea_social.jpg)

Coincidentally, Gibson and Brough shared the first name “Althea”— though Brough preferred to be called Louise—but the solemn Beverly Hills blonde had little else in common with the 23-year-old college student who trounced the Florida Agricultural Mechanical College boys at pool. If some among Gibson’s supporters suspected that the unbalanced draw was likely no accident but was, in fact, a deliberate attempt to ensure that the young interloper would be swiftly vanquished and sent on her way, only a handful said so outright.

Whether the pairing was the hand of fate or an ill-intentioned human strategy, it was clear that this was to be the match of the tournament: the formidable senior champion pitted against the inexperienced newcomer, the seasoned white insider squaring off with the young Black woman with an astonishingly athletic playing style. This was the match that Gibson, not to mention the many who had guided her along the way, had inched toward step by step over the past several years. More than 2,000 eager fans jammed the seats of the club’s grandstand court to see it; guards sealed the gates. While some worried that Gibson couldn’t pull it off, and others were dearly hoping she wouldn’t, few spectators could resist being moved by the sight of the young player nervously pacing the court.

It was a match that would likely never be forgotten by those who witnessed it, not the least because Gibson began so poorly. Unable to get her first service in play, she was repeatedly caught at mid-court by Brough’s aggressive returns. Gibson struggled determinedly to force Brough to the back of the court with her ferocious smash, but she repeatedly overhit. When Brough took the first set 6-1, some in the crowd made their opposition to Gibson’s presence abundantly clear, as Robert Minton wrote in his book Forest Hills: An Illustrated History.

“There were those who did not conceal their hope that she would be beaten and that would be the end of such people at Forest Hills,” Minton wrote.

With the outcome of the match seeming all too clear after the first set, some viewers began to drift out of the stands to matches underway on other courts.

A small army of Gibson’s most avid supporters, who were watching anxiously, remained. Drs. Robert W. Johnson and Hubert A. Eaton, her advocates and mentors, sat together, exchanging observations about their student’s performance, just as they had four years before, when they took her on after an American Tennis Association tournament in Ohio. There was also a large cluster of the Harlemites who had been instrumental in her launch. While the club did not allow Black members to join, Black spectators were permitted to attend the 1950 Championships in what was apparently an exception made on Gibson’s behalf.

As the second set got underway, Gibson had clearly recovered her equilibrium. The first game, seemingly critical if Gibson were to turn the tide, went to deuce time and again, but Brough managed to hold her serve. Emboldened by her opponent’s slowing pace, Gibson grew steadily more forceful with her strokes, and her serve sliced sharply through a gathering wind. With games tied at 3-3, a now visibly tired Brough began to falter. Gibson surged forward, breaking through the older woman’s serve and then claiming the next two games to take the second set 6-3. As some members of the audience leapt to their feet, a ripple of excitement surged through the crowd with the realization that the New York City girl might actually manage to topple one of the world’s greatest female players. So electrifying was the prospect of a potential upset that word went out over the club’s loudspeakers, prompting many spectators of other matches to abandon their seats and rush toward the grandstand.

“At first, a lot of people didn’t bother to watch the match because we all knew that Brough was going to win easily,” recalled Barret Schleicher, a club member now in his 90s who was 18 years old at the time. “But then we heard what was going on, and we went over, and it was true, [Brough] had lost the second set. It was incredibly exciting. It had nothing to do with Black or white, it was that Brough was losing to an unknown. That’s the kind of thing you go to these matches to see.”

As the skies overhead darkened ominously and the winds began to pick up, the third set began. Brough, who appeared to have recovered during the short break, promptly broke Gibson’s serve and took the first three games. But then Gibson seized the momentum and began to play the kind of tennis that left some in the audience gaping. Artfully placing her lobs and following through with crushing overhead smashes, she claimed one game and then lost another. Hundreds of viewers, clearly rooting for Gibson, began shouting and stamping their feet as the battling players inched forward, each claiming one critical game after another.

“It was apparent now that anything could happen, so strongly was Miss Gibson playing and so unreliable was Miss Brough’s service,” wrote the Times’ Allison Danzig.

But not everyone was pleased with the direction the match was taking. High up in the grandstand, a man abruptly stood up beneath the churning dark skies overhead and shouted at the players. What exactly he said is unclear, but some reported he spewed racial epithets.

Whatever words were actually said, they seemed to spur Gibson to even more aggressive play, and she managed to claim two more games, bringing the set to 5-5. Pushing ahead with her brilliant service and a pair of forehand volleys, she claimed the next game. With the outcome now listing in Gibson’s favor, Brough pulled herself together. Running hard in the 12th game to capture each successive lob, she evened the set at 6-6. The clouds, leaden with impending rain, hung ominously low as the winds churned through the grandstand, and the rumble of thunder caused many to tear their gaze from the game and glance briefly upward. Unfazed by the turbulence overhead, Gibson pressed on to take three straight points and pulled into the lead, winning the 13th game and putting the score at 7-6.

And then the rain began, at first just a trickle, but soon a drenching downpour. Debate began over whether to continue. Brough repeatedly asked to postpone until the next day, citing the dimming light. Gibson, a single game away from a momentous conquest, knew she was within reach of victory and earnestly asked to keep on playing.

“Brough was a little cranky. She wasn’t used to losing,” recalls Schleicher. “There was a lot of discussion about whether it was dark enough to call, which is what Brough wanted, to have it called. She didn’t like losing to an unknown player.”

Scriptwriters might have prayed for what came next. Before a decision could be made, the heavens released a torrential rain while bolts of lightning ripped through the black sky. As spectators scurried for cover, a rogue bolt struck one of the stone eagles perched proudly atop the stadium and hurled it to the ground, where it shattered into dozens of pieces. The dramatic moment was surely, some would insist later, a profound message, a sign that the American way was finally changing and that the old order that had kept Black people on the outside was forever done with. Whatever it symbolized, the game was suspended and set to continue the following day.

That decision was, as Gibson later wrote, the worst thing that could have happened for her. “It gave me the whole evening—and the next morning, too, for that matter—to think about the match,” she wrote in her autobiography. “By the time I got through reading the morning newspapers I was a nervous wreck.”

When play resumed in the middle of the following day, the stage was set for a momentous finale. Five motion-picture cameras were trained on the court, with 15 cameramen at the ready. Members of the press clustered at the fence, pads in hand, as the grandstand churned with an overflow crowd yet again. Gibson, who rarely did well under pressure, was late to the game, possibly exercising a deliberate delaying strategy in an effort to unnerve her opponent, just as the great tennis champion Bill Tilden had done decades earlier. But in Gibson’s case, the technique appeared to backfire. By the time she showed up, the cameramen were bursting with expectation, and their flashbulbs exploded mercilessly, compounding Gibson’s obvious state of anxiety. Play began immediately, as the crowd grew quiet in anticipation.

It was over in just 11 minutes. Keenly aware that if she lost the opening game, her name would go down in history in a very different way from that to which she was accustomed, Brough hit with deliberate and forceful precision, swiftly bringing the score to 7-7. In the next two games, Gibson double-faulted repeatedly, netted several shots and generally failed to bring her play up to the previous day’s level. As her final backhand soared off court, the match was called for Brough with a final set of 9-7.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/65/bb6574fd-1205-46dc-9926-cd80362ee369/gettyimages-515181664.jpg)

“I have sat in on many dramatic moments in sports, but few were more thrilling than Miss Gibson’s performance against Miss Brough,” sports reporter David Eisenberg of the New York Journal-American recalled a few years later. “Not because great tennis was played. It wasn’t. But because of the great try by this lonely, and nervous, colored girl, and because of the manner in which the elements robbed her of her great triumph.”

While Gibson did not win the match, she scored a seismic victory for the history books in the eyes of many, particularly those of the Black media. “Althea Gibson’s Amazing Tennis Thrills America” proclaimed the New Journal and Guide. “Althea Did a Splendid Job,” trumpeted the New York Amsterdam News on its front page. The paper ran an accompanying story that gave a blow-by-blow account of the match and concluded, “It was generally conceded that Miss Brough was saved from defeat on Tuesday by the rain.” Brough was quoted as saying, “The rain was probably the only thing that saved me. Althea was playing magnificently, and my game had all but virtually collapsed. … She plays a beautiful game—all she needs is a little more experience.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/c5/84c5ddec-fb69-4aac-bcc6-cc61c578b065/althea_gibson_tennis_outfit-resize.jpg)

The New York Herald Tribune, in an editorial titled “Fine Achievement,” declared that Gibson “did not come through the tournament with a crown of victory, but she won something she can cherish throughout her life and which never can be taken from her—the respect and admiration of all who saw her play this week at Forest Hills. She is a credit not only to the Negro race but to all good sportsmen and women who play and love the game of tennis.”

Eaton and Johnson, her mentors, were just as pleased. While they were disappointed that the match had been plucked from Gibson’s grasp, Eaton wrote in his autobiography, “Our overwhelming feeling was one of triumph. The fact that Althea Gibson, an American Negro, had played at Forest Hills was the important thing. Whether she won or lost was secondary to this accomplishment.”

From Althea: The Life of Tennis Champion Althea Gibson by Sally H. Jacobs, copyright © 2023 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press. On sale August 15, 2023.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(2100x1650:2101x1651)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a3/e7/a3e7897f-2419-4cee-b443-6009309d8c33/gettyimages-97226092.jpg)