The Spy in the Doll Shop

The FBI was confounded by mysterious letters sent to South America, until they came across New York City proprieter Velvalee Dickinson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/bd/b1bd7582-08bf-4f73-bac6-6ba82b02b3fc/1072x804-velvaleecollage.jpg)

Velvalee Dickinson’s secret began to unravel with a letter sent from Springfield, Ohio, to Buenos Aires. U.S. postal censors had intercepted a January 27, 1942 missive from Mrs. Mary Wallace to Señora Inez Lopez de Molinali. The letter proved undeliverable, and its typewritten contents were suspicious and perplexing. It was turned over to the FBI.

One odd passage read: “The only three dolls I have are three love Irish dolls. One of these dolls is an old fisherman with a net over his back, another is an old woman with wood on her back and a third is a little boy.” Could such innocuous “doll talk” mask something more suspicious?

From then until August 1942, a total of five such letters surfaced, all from different correspondents and all, except Mrs. Wallace, living west of the Rockies. Agents interviewed the five women: each recognized her signature but denied either writing the letter or knowing any Señora Lopez de Molinali. If so, who was actually writing them? Argentina-bound mail was being closely monitored because of that nation’s fascist leanings. ‘Señora Molinali” either never existed or was an Axis front. The chatty letters, meanwhile, might violate wartime postal censorship regulations, supplying information that purposely or inadvertently helped the enemy.

Soon the focus narrowed. Each woman was a doll collector and each had corresponded with a diminutive 50-year-old New York City dealer named Velvalee Dickinson who, it turned out, had unusually cozy pre-war ties with the Empire of Japan.

The FBI investigation (summarized in government case files) determined the Sacramento-born, Stanford-educated, twice-divorced Velvalee had moved from San Francisco to New York in the fall of 1937. She took rooms in the Hotel Peter Stuyvesant on Manhattan’s West 86th Street with her ailing third husband Lee Taylor Dickinson. The two had met when Velvalee kept books for Lee’s California produce brokerage. The firm had many Japanese clients, so it was not surprising the couple became active in the Japanese-American Society. Yet oddly, when “shady dealings”, as described by the FBI, brought the business down and caused them to be kicked out of the Society, a Japanese diplomat stepped in to reinstate the Dickinsons and underwrite their Society dues.

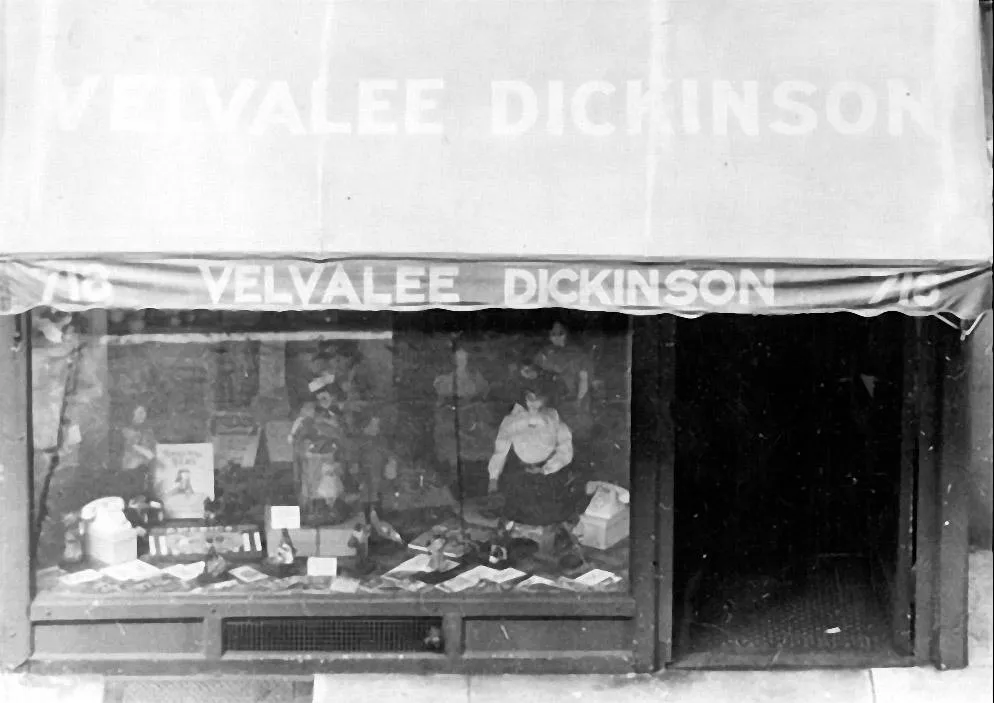

Now relocated to Manhattan, Velvalee worked the 1937 holiday season as a sales clerk in Bloomingdale’s doll department. According to doll historian Loretta Nardone, costume doll collecting was then a burgeoning pastime bolstered by local clubs, specialty dealers and avid hobbyists, including Velvalee. Velvalee established her own doll business early the following year, first out of an apartment at 680 Madison Avenue, and eventually in the storefront at 718 Madison. The Dickinsons and their live-in maid resided just across the street.

Velvalee promoted her business via correspondence with collectors (such as Mary Wallace) and advertising in House Beautiful and Town and Country, but when agents began investigating the business, the FBI doubted that the income could surpass the expenses, which included extravagant purchases of audio records. One confidential informant (most likely Velvalee’s store clerk or her maid) complained of getting “sick and tired" of returning phonograph records” purchased by Velvalee. The feds were also suspicious of her travel expenses: “the subject [Velvalee] made at least one trip to California every year on business and pleasure.” Despite the demands of business and Lee’s precarious health--he died in March 1943-- she joined New York’s Japanese Institute and frequented the Nippon Club.

A November 26, 1941, visit to 718 Madison by a “well-dressed Japanese” may have held the key to Velvalee’s suspect prosperity. As recounted in a 1944 edition of St. Louis Sunday Morning, the Japanese visitor “darted through the door and…handed a small, compact bundle to the proprietor.”

“‘I may not be able to come again,’ he said. The proprietor replied that they might meet again, perhaps in Honolulu, ‘No, No!’ the Japanese exclaimed, ‘Not Honolulu.’”

***

The net finally dropped on January 21, 1944. Velvalee “fought bitterly” as FBI agents arrested and handcuffed her at a Midtown Manhattan bank. Agents found $15,940 in her safe deposit box, two-thirds of it in Federal Reserve notes traceable to the Japanese Consulate. During Velvalee’s arraignment on dual charges of espionage and violation of wartime censorship codes, bail was set at $25,000. “No photographs!” Velvalee yelled as she was led away. The judge temporarily honored that request, but refused another: Velvalee could not bring her records or her record player to jail.

A federal grand jury indicted Velvalee two weeks later, after which she faced prosecution by U.S. Attorney James B.M. McNally, who boasted a 98 percent conviction rate. (One of his minor coups was stripping citizenship from Erika Segnitz Field, a New York woman who’d trained her parrot to scream “Heil Hitler!”)

The government’s evidence included the Federal Reserve notes and the testimony of confidential informants. It also proffered forensic proof concerning the Argentina-bound letters: Their signatures were forged and each letter had been prepared using hotel typewriters rented by the Dickinsons. Furthermore, the dates and locations of their postings coincided with the couple’s travels to areas where the letters supposedly originated. According to the government, the conspiracy fell apart when the Japanese, unknown to Velvalee, deactivated the address in Buenos Aires used to retrieve espionage reports.

FBI cryptographers were even ready to testify as to the sinister (albeit circumstantial) meanings contained in the letters themselves. They alleged that Velvalee used a rudimentary “open code,” substituting entire words instead of individual letters to pass secrets on American warship conditions and locales.

For example, the three “dolls” mentioned in Mrs. Wallace’s letter were U.S. Navy ships under repair in West Coast shipyards: The “old fisherman with a net over his back” was an aircraft carrier shielded by an anti-submarine net; the “old woman with wood on her back” was a wooden-decked battleship; and the “little boy” was a destroyer.

Velvalee’s trial, originally slated for June 6, 1944, was postponed due to the excitement surrounding the D-Day invasion of Europe. By July 28, however, the defendant--already described as “The War’s Number 1 Woman Spy”--was willing to accept a deal. With the espionage count dropped, Velvalee pled guilty to the censorship violations.

Velvalee was sentenced on August 14. Dressed in black, except for white knit gloves, and now weighing just 90 pounds, a weeping Velvalee asked for mercy, claiming Lee had been the actual spy. “It’s hard to believe,” scolded the judge, “that some people don’t realize that our nation is engaged in a life-and-death struggle.” He gave Velvalee the maximum sentence: ten years imprisonment and a $10,000 fine. She would serve her time at the Reformatory for Women, Alderson, West Virginia. (Six decades later, under the nickname “Camp Cupcake,” Alderson would incarcerate style doyenne Martha Stewart, convicted of insider trading.)

When Velvalee was finally paroled on April 23, 1951, she returned to New York and (according to a 1952 magazine account) began employment at a city hospital. Her parole ended in 1954 and she is believed to have died, unnoticed, in 1961.

718 Madison Avenue now houses Beretta Galleries, the flagship store of the Italian arms manufacturer. There remain no traces of Velvalee’s conspiracy, but the current proprietor still evokes espionage lore. After all, Beretta’s tiny M418 "pocket pistol" was an early favorite of James Bond.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David31_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David31_copy.jpg)