The Nazis’ Plan to Infiltrate Los Angeles And the Man Who Kept Them at Bay

A new book explores the deadly and nefarious plots designed by Hitler and his supporters

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/fc/85fc25b9-d067-4623-aae1-82d838bffd2a/28-anti-nazi-protestaug-1938.jpg)

Men in armbands stand below an American flag, flanked by Nazi symbols and a portrait of Hitler. In another photograph, swastika flags line Broadway Street in Los Angeles. The cover of historian Steven J. Ross’s new book looks like something straight out of the beloved novel The Man in the High Castle and television series of the same name.

But these aren’t doctored images and no, you’re not about to crack open Philip K. Dick’s alternative, dystopian tale. In Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America, Ross, a professor at the University of Southern California, uncovers the fascinating, complex story of how Nazis infiltrated the region and recruited sympathetic Americans to their cause. While American Nazis were working on plans and ideas to subvert the government and carry out acts of anti-Semitic violence, Leon Lewis created a network of spies to stop them.

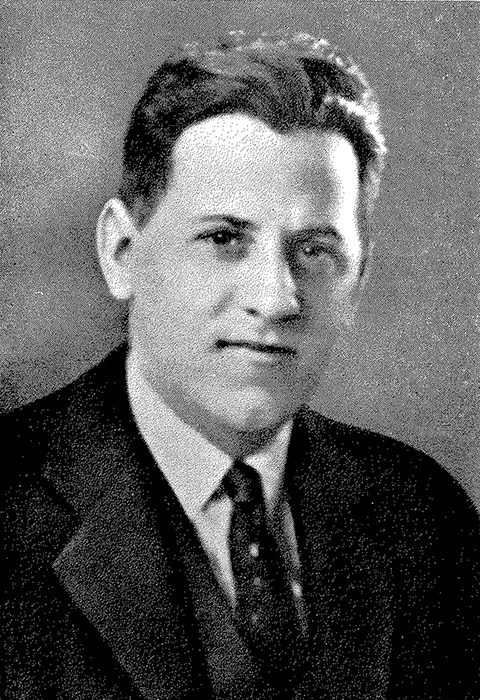

A Jewish lawyer and WWI veteran, Lewis was the founding executive secretary of the Anti-Defamation League. Throughout the 1920s and early '30s, he tracked the rise of fascism in Europe both for the organization and on his own. As Ross related in an interview, “I think it's safe to say nobody was watching Hitler more closely during those years than Lewis.”

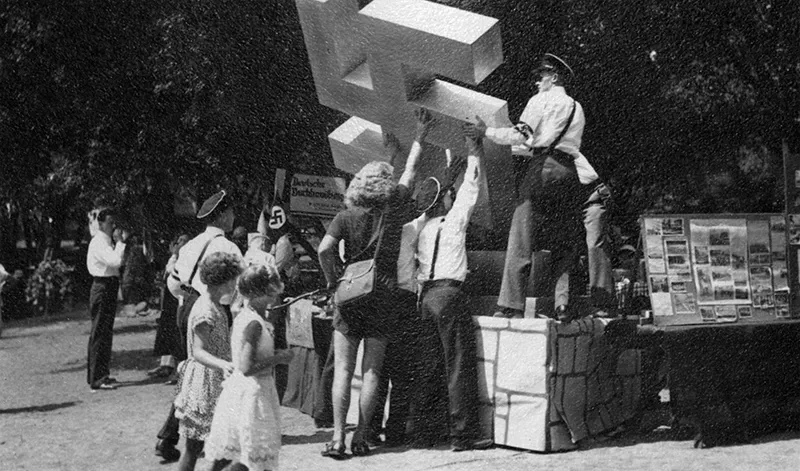

After Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933, Nazi officials sent agents to the United States to start the Friends of New Germany (FNG) organization—later renamed the German American Bund—intended to bolster support overseas. That July, Nazis held a rally in Los Angeles and started meeting and recruiting at their Deutsche Haus headquarters downtown—beginning a cycle Lewis was all too familiar with.

As Ross writes, “Lewis knew from years of monitoring the foreign press that the Nazi government encouraged Germans living in the United States to form ‘active cells wherever sufficient numbers of Nationalist Socialists can be gathered into proselytizing units.’” Central to the Nazis’ mission was cultivating fifth columnists—“disloyal forces within a nation’s border”—who could be called upon to side with Germany if war began. It was clear to Lewis that it was time to act, but he found the Jewish community divided as to how best to combat rising anti-Semitism, and the U.S. government was more concerned with tracking Communism than fascism.

So Lewis organized a spy ring on his own, focusing on the same people the Nazis were hoping to recruit: German-Americans veterans. Just as Hitler had channeled the frustration of World War I veterans and struggling citizenry in Germany to help elect him, his supporters in Los Angeles hoped to stir up feelings of resentment among those who were disgruntled by cuts to their veteran benefits during the Depression.

Southern California was a particularly appealing locus: about one-third of disabled veterans lived there, and the region had 50 German-American organizations with 150,000 members, which the Nazis hoped to unite. Compared to New York City, the port of Los Angeles was largely unguarded, perfect for trafficking in propaganda from Germany. Additionally, the area was ripe for Nazi messaging: it was one of the strongest centers outside of the South for the Klu Klux Klan, with large gatherings held throughout the 1920s.

But Lewis, who knew a number of German-American vets from his work with the Disabled American Veterans, appealed to his spies’ sense of patriotism. The spies, Ross said, “risked their lives because they believed that when a hate group attacks one group of Americans, it's up to every American to rally to defend them.” And their loyalty to Germany didn’t translate to Hitler; many despised him for what he had done to their ancestral nation. Save for one Jewish spy, Lewis’s network was comprised entirely of Gentiles.

Initially, Lewis planned to spy just long enough to find evidence to convince local and federal officials of the real danger Nazis posed to Los Angeles. But when he presented his first round of findings, he was met with ambivalence, at best; he discovered a number of L.A. law enforcement personnel were sympathetic to Nazism and fascism—or were members of the groups themselves. Without serious government attention, Lewis realized he would need to keep his operation going. He decided to solicit financial support from Hollywood executives—who were also the targets of some of the unearthed plans and whose industry was at the core of Hitler’s machinations.

Before the various theaters of war opened in the late '30s and early '40s, the Nazis trained their eyes on the theaters in Hollywood. Hitler and his chief propagandist, Joseph Goebbels, realized the power of the film industry’s messaging, and they resented the unsavory portrayals of WWI-era Germany. Determined to curb negative portrayals of the nation and Nazis, they used their diplomats to pressure American studios to “create understanding and recognition for the Third Reich,” and refused to play films in Germany that were unfavorable to Hitler and his regime.

Lewis’s network of spies, many of whom were trusted by top Bund officials in L.A., reported on and worked to interrupt a wide range of haunting plots, including the lynching of film producers Louis B. Mayer and Samuel Goldwyn and star Charlie Chaplin. One called for using machine guns to kill residents of the Boyle Heights neighborhood (a predominantly Jewish area), and another conspired to create a fake fumigation company to surreptitiously kill Jewish families (a chilling precursor to the gas chambers of Nazi concentration camps). Lewis’s spies even uncovered plans to blow up a munitions plant in San Diego and to destroy several docks and warehouses along the coast.

There was talk of seizing National Guard armories and setting up a West Coast fortress for Hitler after Germany’s planned invasion and ultimate takeover the U.S. government. The many plans were drafted by local fascists and Nazis but the leaders, Ross explained, “would have undoubtedly told officials in Berlin, most likely by handing over sealed letters to the Gestapo officer who accompanied every German vessel that docked in L.A. from 1933 until 1941.”

Lewis and his spies were able to break up these plots through a variety of means: by sowing discord between leaders of the Bund, getting certain plotters deported or into legal trouble and fostering a general sense of distrust among members that spies had infiltrated the group.

While Ross doesn’t think the Germans would have prevailed in overthrowing the government, he contends that many of the schemes were serious threats. “I uncovered so many plots to kill Jews that I absolutely believe, had Leon Lewis' spies not penetrated and foiled every single one of those plots, some of them would have succeeded,” he said.

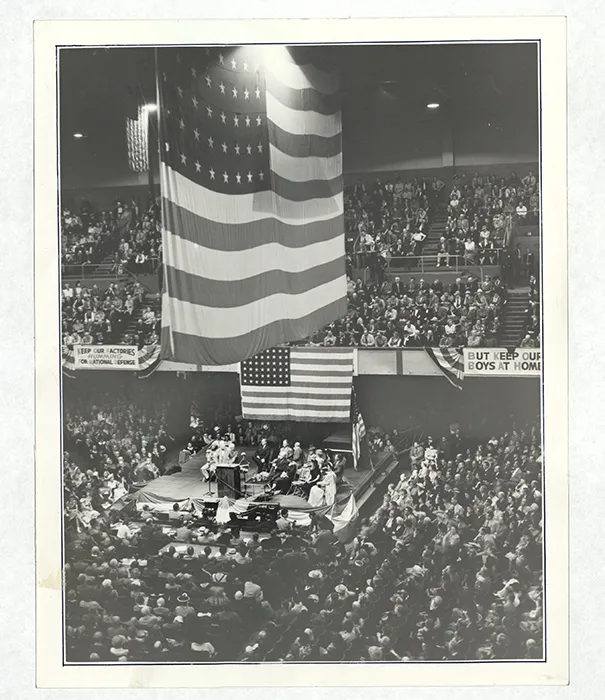

On December 8, 1941—the day after Pearl Harbor and the U.S.’ entrance into the war—when the FBI needed to round up Nazi and fascist sympathizers, Lewis was able to provide crucial information on operations in California. Yet Lewis continued his spy ring even after the U.S. declared war on Germany, because he found a “dramatic rise in anti-Semitism as greater numbers of citizens blamed Jews for leading the nation into war.” His spy operations ceased in 1945, once the war came to a close.

At its core, Hitler in Los Angeles subverts the idea that there wasn’t active and significant resistance to Nazism in America before WWII. Even decades later, it’s easy to wonder why more wasn’t done to prevent Hitler’s rise and Nazi atrocities, and to point out the warning signs that now seem obvious. But Ross’s research makes clear there was a contemporary understanding and opposition, well before the rest of the US realized the scale of Hitler’s plans, even if the story went untold for so long.

The son of Holocaust survivors, Ross said that researching this book has changed how he thinks about resistance: “They stopped this without ever firing a gun, without ever using a weapon. They used the most powerful weapon of all…their brains.”

But the book also challenges an idea many Americans take comfort in—that “it can’t happen here.” In a sense, it did happen here: Nazism and fascism found a foothold in 1930s Los Angeles and attracted locals to its cause. And while Lewis’s dedication helped thwart it, it’s alarming to consider the alternate history wasn’t far off.