After Victory in World War II, Black Veterans Continued the Fight for Freedom at Home

These men, who had sacrificed so much for the country, faced racist attacks in 1946 as they laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement to come

:focal(403x266:404x267)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/a7/d7a79883-ba0a-49b8-8027-73099d56764a/1946_v3.jpg)

In December 1946, in Palo Alto, California, flames consumed the newly constructed home of John T. Walker, a Black veteran just back from serving in the Navy during World War II. Arsonists left a note that read:

We burned your house to let you know that your presence is not wanted among white people. You should know by now we mean business. Niggers who are veterans are making a mistake thinking they can live in white residential districts.

The arsonists struggle to reconcile their racism with the respect they know veterans have earned, adding:

Since you are a veteran, we are warning you for the last time to clear out. If you were not a veteran, you would be dead now. Usually the Klan strikes without warning, but since you are a veteran, we have been unusually kind in giving you a chance to save of your black hide."

Walker’s experience was by no means exceptional. He was among the 900,000 Black servicemembers who returned home from the war only to receive a welcome message that was essentially, “Thank you, but no thank you, for your service.” Even worse, in the Jim Crow South, home to three-quarters of the Black servicemembers, many attacked these veterans when they sought to exercise the very freedoms for which they had fought.

“Every effort was made to make this absolutely clear… The war has changed nothing in regards to race relations,” says Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Leon Litwack. “What [hostile white communities] failed to note: Black Americans are no longer willing to take it.”

The year 1946 proved a turning point in Black resistance to legal segregation in America, in large part because of the efforts of Black veterans. In the face of assaults, lynchings and police brutality, these Americans stood at the vanguard 75 years ago when they mounted challenges to long-denied access to housing, employment, political participation and social integration. They made 1946, in Litwack’s words, “the true birth of the Civil Rights Movement.”

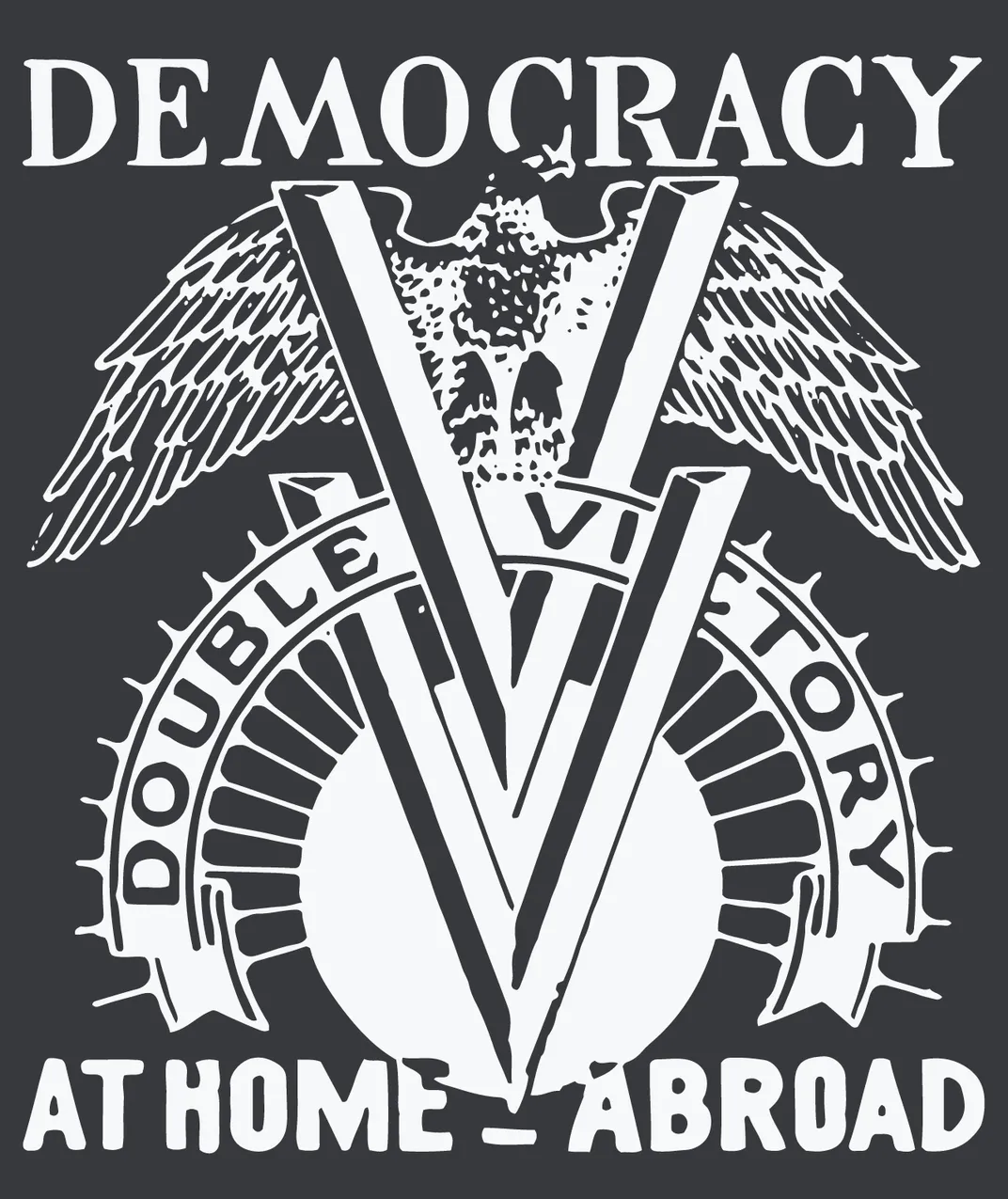

At the start of the war, Black Americans made a pact with their country: They’d fight this war, but the nation would have to recognize them as full citizens when they return. In December 1941, the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper, published a letter from James G. Thompson, a Wichita, Kansas, defense-industry worker, who wrote:

“[I]nsofar as the ‘V for Victory’ sign for the allied combatants meant “victory over aggression, slavery and tyranny…, then let colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory: The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies within.”

Thompson plainly asked, “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?” Inspired by Thompson’s letter, the Courier launched “The Double V Campaign,” rallying African-Americans to demand full citizenship rights at home in exchange for their collective sacrifices abroad.

The perversity of the United States fighting Hitler’s master-race ideology with an army segregated by race was not lost on African Americans. Military service was also a fresh humiliation for Black enlistees who had never experienced segregation. “Whether one was a graduate of Harvard Law School or was a sharecropper in Georgia with a second-grade education, he was swept into the same brutally segregated American military,” says Rawn James, Jr., author of The Double V—How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America’s Military. “That united African Americans under one common cause that would have a tangible benefit for all of them.”

Nazi leaders understood this American hypocrisy and sought to humiliate and demotivate Black soldiers further by confronting them on the topic. “The Germans would drop leaflets on [the black troops] and mock them for serving in a military that would treat them as less than human beings,” says James. “They’d say things like, ‘You’ve done this before, look what it got you. What’s the matter with you?’”

The pride and humiliations of the Black war experience grew the membership rolls of the NAACP, whose ranks grew tenfold from 50,000 in 1940 to 450,000 in 1946. The civil-rights organization would need this war chest, as white Southerners redoubled efforts post-war to preserve their economic, political, and social subordination of their Black neighbors. These efforts arose partly out of a fear that returning African Americans would refuse to work the farms as sharecroppers, and a great many did indeed leave the South altogether.

“White farmers are losing their minds,” says historian Kari Frederickson. “The inability to control that captive labor force, which then brings with it all sorts of other types of control, in many ways is at the heart of this racial explosion that happens in 1946.” Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland, speaking from the Senate floor, declared that white soldiers from the South expected to come home and find “the integrity of the institutions of the South unimpaired” and that “those boys are fighting to maintain white supremacy.”

Senators also fired missives off to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was leading the U.S. effort in Europe, to also discourage black soldiers from mixing with whites while stationed in England and Germany lest they would return home demanding such freedom. In December 1945, U.S. senator Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi told Eisenhower, in a two-page letter, that “negrophile” forces were advancing social equality in America, which he warned “inevitably leads to familiarity, miscegenation, mongrelization, and in many cases intermarriage between the races.” In closing, he told the general that continued segregation in America “was almost as important as the control of the atomic bomb.”

In July 1945, Eastland expressed similar anxiety in a floor speech, stating that, “In Europe the Negro has crossed the color line” and “has gone with white girls.” He warned, “there will be no social equality…when the soldier returns.” Similarly, Alvin Owsley, a Roosevelt administration diplomat, veteran and former head of the American Legion, fired off a September 1946 letter to Eisenhower the day that Newsweek published “four photographs showing the white women of Germany in the arms of, dancing with the blackmen [sic] in the uniform of the United States Army.” For this “disgraceful,” “repulsive” and “obscene” display, Oswley told Eisenhower, “[The black men] very likely are on the way to be hanged from the limb of some big oak tree or to be burned alive at public lynchings by the white men of the South.”

But the greatest threat to Jim Crow and the greatest promise for black self-determination was voting rights. The Supreme Court, in its 1944 Smith v. Allwright, decision, ruled that the Democratic Party must allow Black party members to participate in its “all-white primary,” offering Black southerners the first meaningful chance to participate in elections in nearly 75 years. This primary effectively decided the general election winners in the solidly Democratic South. Black votes meant Black people could pass laws, serve on juries, shape their own lives, and the course of the nation. Historian Patricia Sullivan noted, an estimated 600,000 Black southerners registered to vote in 1946, a threefold increase over the 200,000 recorded in 1940. “One additional [Black] voter on the roll is too many [for the White political class],” Fredrickson says, describing the anxiety this caused. “It’s a minority of those who are eligible to vote but it’s more than white people thought it should have been.”

Medgar Evers, whose murder would later galvanize the civil rights movement, began his activism in 1946, when he and his brother Charles returned from military service and organized a voter-registration drive in Mississippi. The group looked forward to voting in the midterm election against Bilbo, who had warned in public speeches that blacks attempting to vote would be prevented by “red blooded whites” at the polls. Armed groups threatened Evers at his home and then again when he and other Black veterans ventured out to register and vote, but the veterans would not back down.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/62/f062ab2c-fcb8-4a95-86df-f73f1331f38d/screen_shot_2021-08-27_at_43212_pm.png)

Black Mississippians petitioned Congress to investigate Bilbo’s interference with Black voter participation in the primary. The chair of the U.S. Senate Committee to Investigate Campaign Expenditures, Louisiana Democrat Allen Ellender, a self-confessed white supremacist, initially declined to conduct a serious investigation. Ultimately, he yielded to the demands from civil-rights-minded senators and held field hearings in Jackson, Mississippi in December of 1946. NAACP attorney Charles Hamilton Houston, the godfather of civil rights law, providing an eyewitness account of the hearings for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper, wrote, “[T]wo hundred veterans packed the corridors of the courthouse volunteering to testify…,” risking “possible reprisals against their property, businesses and families…[F]or the first time in over fifty years, the stinking record of terror and intimidation was exposed in a public statewide hearing.”

Meanwhile, that July in Georgia, veteran Maceo Snipes defied threats from the Klan to become the first African-American in Taylor County, Georgia, to cast a ballot, voting in that state’s gubernatorial primary. The next day, four white men called Snipes out of his home; one of them shot Snipes in the back. He died a few days later after a white hospital denied him a transfusion because it had no “black blood” on hand. An all-white jury acquitted Snipes’ killer, accepting his defense that Snipes had attacked him over a disputed debt.

Just a few days after Snipes’ death, a Walton County, Georgia, mob of 15-to-30 white men lynched George Dorsey, a black veteran, his pregnant wife, Mae, and another black couple, Roger and Dorothy Malcom. The couples were on their ride home from the county jail, where Roger had been released on bail after stabbing a white farmer during a dispute. The mob hung the four from trees near the Moore’s Ford Bridge.

In its investigation of the murders, the FBI even scrutinized the actions of Eugene Talmadge, the segregationist former governor and candidate in the 1946 gubernatorial primary. In a memo to bureau director J. Edgar Hoover, investigators reported that Talmadge had allegedly promised to the brother of the stabbed farmer that, if elected, he’d grant immunity to anyone “taking care of [the] Negro” responsible for the stabbing.

The town’s assistant police chief believed the message of this visit tipped the county’s vote in Talmadge’s favor. The Moore’s Ford lynchings prompted a 17-year old Dr. Martin Luther King to write an August 1946 letter to the Atlanta Constitution condemning the act and stating, on behalf of everyday African-Americans, “We want and are entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens.” No one has ever been charged for the murder of the two couples.

To intensify the call for a federal response to these lynchings and assaults on black veterans, Walter White, the executive secretary of the NAACP, formed the National Emergency Committee Against Mob Violence (NECAMV) in August. The violence had reached a fever pitch “that terrible summer of 1946,” as White dubbed it. The actor and future President Ronald Reagan took to airwaves, declaring, “I have to stand up and speak,” where he hosted the radio program, “Operation Terror,” in which he decried the Georgia lynchings and dozens of attacks in California.

The NAACP’s call to action was a response to much more than the Moore’s Ford lynchings. Rather it was the culmination of a stream of reports it had fielded, starting with a February attack on the black population of Columbia, Tennessee. “That’s where you have a Black community defending itself from a pogrom, the next Tulsa,” says Emory University historian Carol Anderson. The conflict began when James Stephenson, a 19-year-old Navy veteran of the Pacific theater, got into a scuffle with a white store clerk after his mother had complained about the shoddy repair of a radio. The clerk punched Stephenson in the back of the head when he was exiting the store. Stephenson, a boxer, returned the blow, and the clerk fell through a glass store window. The fight spilled onto the sidewalk, where bystanders broke it up. When police arrived, they arrested and jailed the Stephensons only, and charged them with attempted murder.

As rumors of a planned lynching circulated, the sheriff released the Stephensons into the custody of a Black businessman who put the young veteran on a train to Chicago and hid the mother. Meanwhile, police officers, accompanied by a white mob, waded into “Black Bottom,” Columbia’s segregated Black community, announcing it wanted to talk to its residents. Black veterans had taken up rifle positions on buildings, anticipating the mob’s attack. “Columbia was a very important turning point,” adds Litwack. “Whites got a dose of what that meant when Blacks said they would not take it anymore. They would resist and fight for their civil rights.”

African-American sharpshooters shot four advancing policemen with buckshot, causing minor injuries. The next morning, the Tennessee Highway Patrol stormed the community, randomly beating people and ransacking homes and businesses (caskets in one funeral home were defaced with “KKK” graffiti). They stole cash, jewelry and other property, seized private weapons and arrested 100 Black residents.

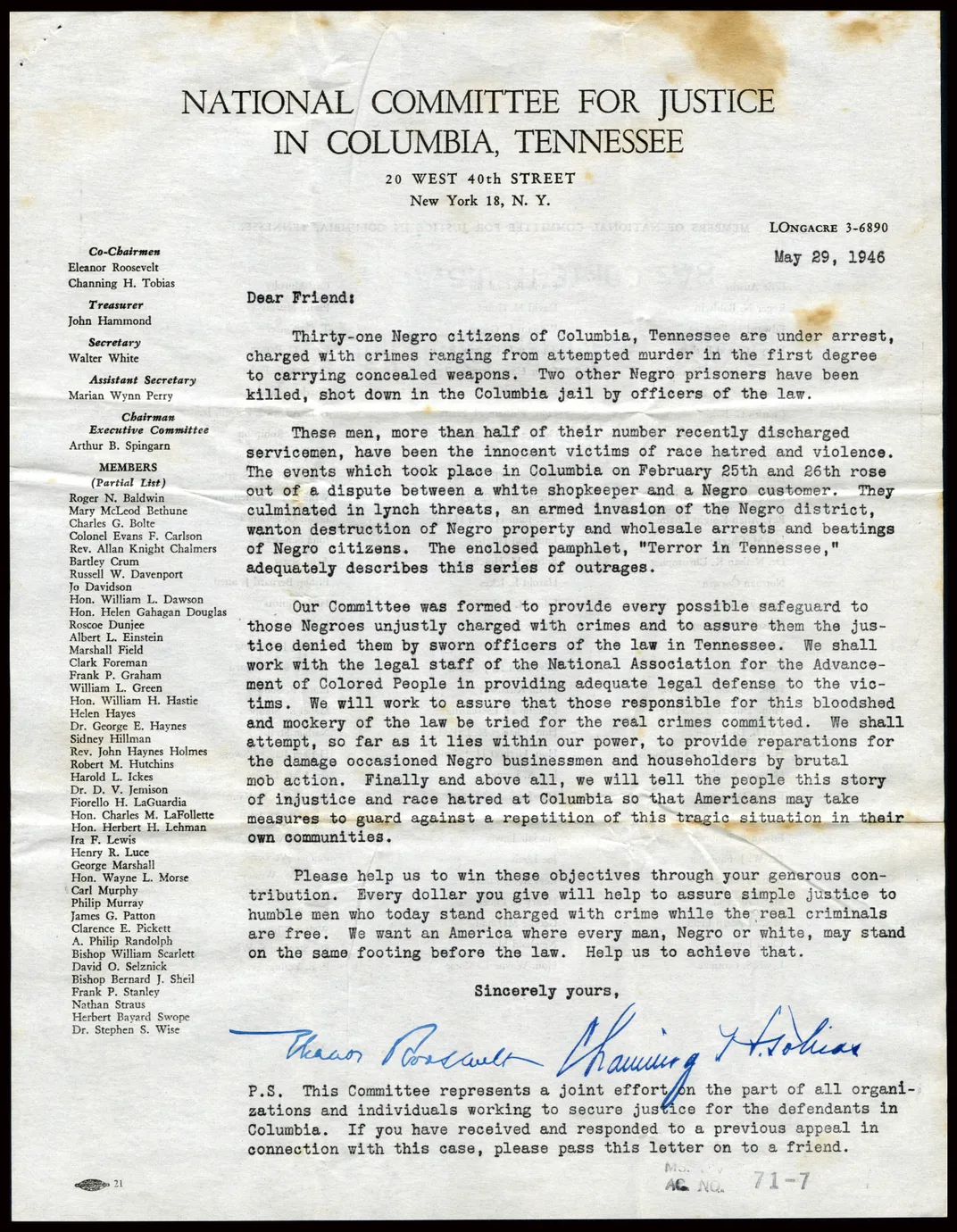

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the first national figures to draw attention to the violence visited upon returning servicemen. In response to Columbia, she co-chaired the National Committee for Justice in Tennessee, whose 50 members included Albert Einstein, labor and civil-rights activist A. Philip Randolph, Hollywood producer David O. Selznick, and famed theater actress Helen Hayes. In a May 1946 fundraising letter, Roosevelt called for the release of the 31 Black Columbia residents (two had been killed in custody), some of whom had been charged with attempted first-degree murder. Roosevelt wrote, “These men, more than half of their number recently discharged servicemen, have been the innocent victims of race hatred and violence.”

That fall, NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall traveled to Columbia, where he helped local attorneys gain the release of the accused men. When Marshall and the lawyers prepared to leave town following the trial, police pursued them and arrested Marshall on false charges of drunken driving. The future Supreme Court Justice narrowly escaped lynching by a mob in the Tennessee woods.

The Columbia, Tennessee, attack was too big for the rest of the country to miss, but the police attack on Army veteran Isaac Woodard that same February—an event which arguably had the greatest singular impact on the course of the American civil rights movement—might never have come to light but for a tip to the NAACP from John McCray, the editor of Charleston, South Carolina’s Black newspaper, The Lighthouse and Informer. Through his own sources, he heard of, and shared with the NAACP, an account of an African-American serviceman pulled off a Greyhound bus in South Carolina and beaten and blinded by a local police chief. Woodard, still in uniform from his decorated service in the Pacific, had just been discharged from Camp Gordon in Georgia and was on his way home to North Carolina.

“He doesn’t even get off the bus without being blinded,” says Richard Gergel, U.S. District Court Judge for South Carolina, and author of The Blinding of Isaac Woodard. “He doesn’t even get home.” Following an exchange with Woodard over a request for a bathroom break, the bus driver summoned the police chief in Batesburg, South Carolina, who then called Woodard off the bus and beats him with his blackjack as the bus pulls off. Later, the officer gouges the uniformed soldier’s eyes out.

But White and the NAACP, who wanted to publicize the case, could gather only some of these facts from McCray’s initial report. Woodard, for example, who had been beaten unconscious, mistakenly told McCray the attack took place in Aiken, South Carolina, so the NAACP could not even confirm the police department responsible. White enlisted his friend, the actor and director Orson Welles, to “publicize and get action on the case” on his ABC radio program, which Welles did, in dramatic fashion, for several straight weeks throughout the summer of 1946.

Gergel, in his account of the Woodard case, wrote, “The response to the national radio broadcast was electric. The NAACP and various government agencies were flooded with messages of concern and protest from black citizens, many of them veterans.” The Welles broadcasts led to the identification of Lynwood Shull as the police chief who assaulted Woodard, with Welles declaring on-air: “I’ve unmasked him. I’m going to haunt Police Chief Shull for all the rest of his natural life. Mr. Shull is not going to forget me. And what’s important, I’m not going to let you forget Mr. Shull.”

Building on the Welles broadcasts, Black newspapers pressed for justice for Woodard and raised funds for his recovery. Woodard embarked on a national speaking tour. New York’s Amsterdam News arranged a benefit concert featuring Count Basie and Billie Holliday, among others. Woody Guthrie performed “The Blinding of Isaac Woodard,” an 11-verse song he composed for the occasion.

In a September 1946 visit to the White House, the NAACP’s committee highlighted the Woodard case in its appeal to Truman to address violence against veterans. “That incident,” said Gergel, “just riveted Harry Truman,” a World War I veteran. “The decorated uniformed soldier who can’t even get home.”

Truman then pursued what Gergel said was America’s first prosecution of a police officer, or of any white person, for excessive force against a black person, despite the long history of police involvement in the murder, lynching, and assault of Black civilians. “It was white immunity,” says Gergel, who was the presiding judge in the trial of Dylann Roof for the 2015 murder of nine worshippers in an African-American church in Charleston.

Days after the White House meeting, the Department of Justice announced its prosecution of Shull. Then, in December, Truman announced the formation of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, which would issue a 1947 report, “To Secure These Rights,” recommending federal action to address mob violence and police brutality against African-Americans and other systemic deprivations of rights. The report also condemned discrimination in the armed forces. It advocated that desegregation of the military could illustrate to the country, the “practicability of American ideals as a way of life.” On July 26, 1948, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, to do just that. “It really is my fervent belief that the desegregation of the military was the first victory of what we now call the civil rights movement,” says Rawn James, Jr. “It had a fantastic effect on the country.”

While the Woodard case would be instrumental in toppling many decades of legal segregation in America, Woodard himself did not obtain justice in court. An all-white jury acquitted Shull in 28 minutes. The injustice of the case, however, did awaken in the presiding judge, U.S. District Court Judge J. Waties Waring, a determination to squarely challenge the Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” doctrine, which had provided the legal justification for segregation since 1896.

Gergel says that for anything to change, someone like Waring—a patrician judge, son of a Confederate war veteran—would have had to strike at the heart of the racist judicial system. “All these people are saying, ‘We gotta fix this.’ Well, that’s fine, but how do you do it?” Gergel asks. “How do you do it when the people adversely affected are disenfranchised, have no voice? The people who are in power have no interest in changing it, and the federal government is a bystander. There seemed to be no fix.”

Waring used his background to his advantage. When Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP filed the school desegregation case Briggs v. Elliott in Waring’s court in 1950, the judge nudged the plaintiffs to directly challenge the constitutionality of state’s segregation statute. The case then would require a three-judge panel, where Waring would be the first federal judge in 55 years to question the constitutionality of the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Court rules would rocket the case directly to the Supreme Court who would then have to wrestle with Waring’s dissent, challenging Plessy. Which is what happened. Briggs would be bundled with four other cases before the Court, known jointly as Brown v. Board of Education. In Brown, the Supreme Court struck down de jure segregation in the United States.

In truth, 1946 is not that long ago. “I remember being outraged by it,” said Litwack, 91, recalling the beating and blinding of Isaac Woodard. “It shook me up.” Litwack, a teenager at the time, was editor of his California high school newspaper. He remembers putting out a special issue on the atrocities visited upon black Americans that year. “Whites felt very threatened by any signs of Black success,” he recalls.

Litwack questioned the history his textbook taught about America’s Reconstruction era—roughly, the 75 years leading up to 1946. This led to a life as an historian, advancing the scholarship on slavery, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era. And when one reviews the 75 years since the violence and the government-sanctioned discrimination of 1946, it is remarkable how much African-Americans have achieved in a short span. Anderson, the historian from Emory, laments that many Americans don’t want to teach this history. “Because then the U.S. doesn’t make sense. Segregated neighborhoods don’t make sense. All-Black and all-white schools just don’t make sense.” She cites also the G.I. Bill, which black servicemembers could not use to join the emerging middle-class in the suburbs. “The wealth gap [today]…Imagine if that that black veteran was able to hold onto that house in Palo Alto. That family would have some money, right?”

Seventy-five years later, some battles remain.