The Surprising Ingenuity Behind “Goodnight Moon”

Author Margaret Wise Brown used new theories in childhood education to write the classic children’s book

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ee/d8/eed8c19e-193f-452a-bab7-886a55d0d86b/22_fox-eyes_hires-wr.jpg)

The plot could not be simpler: A young bunny says goodnight to the objects and creatures in a green-walled bedroom, drifting gradually to sleep as the lights dim and the moon glows in a big picture window. Goodnight Moon has sold more than 48 million copies since it was published in 1947. It has been translated into at least a dozen languages, from Spanish to Hmong, and countless parents around the world have read it to their sleepy children.

Author Margaret Wise Brown, subject of a new biography, based Goodnight Moon on her own childhood ritual of saying goodnight to the toys and other objects in the nursery she shared with her sister Roberta, a memory that came back to her in a vivid dream as an adult. The text she jotted down upon waking is at once both cozy and unsettling, mimicking and inducing the unmoored feeling that comes with drifting away to sleep. Unlike so many children’s books, with their pat plots and clumsy didactics, it’s also one that parents can stand rereading—and not only for its soporific effect on their sons and daughters.

Reviewers have described the book as less a story than “an incantation,” and writers on the craft of writing have labored to tease out the strands of its genius. This exercise feels dangerous, since a close reading may raise more questions than answers (when was the bunny planning to eat that mush, anyway?). But while the book’s relationship to reality may be slightly askew, it also feels true to childhood, a period when, as Brown was quick to note, the world adults take for granted seems every bit as strange as a fairy story, and the pleasure of language lies less in what it communicates than in its sound and rhythm.

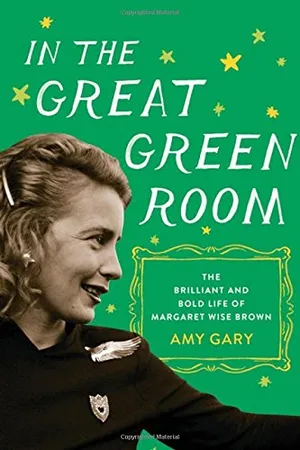

She may not be a household name like Beatrix Potter or Dr. Seuss, but with her innovative insights into what the very young really want to read about, Margaret Wise Brown (1910-1952) revolutionized children’s literature. The new book, In the Great Green Room, is by author Amy Gary, who bases her account of Brown’s “brilliant and bold life” partly on a trove of unpublished manuscripts, journals and notes that she discovered in Roberta’s hayloft in 1990. Over more than 25 years, as Gary pored over reams and reams of fragile onionskin that had been left untouched since Brown’s sudden death at age 42, the biography gradually took shape—and the woman who emerged was no less charming and strange than her most famous work.

Born into a wealthy family and raised on Long Island, Brown came to children’s literature in a roundabout way. In college, she admired Modernist writers like Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein, although she devoted more energy to the equestrian team than to academics. After breaking off an engagement with a well-bred beau (she overheard him laughing with her father over how to control her), she moved to Manhattan to pursue a vague literary ambition, living primarily on an allowance from her parents.

Brown loved the hustle and bustle of city life, but the short stories she wrote for adults failed to interest publishers. Feeling pressure from her father to either marry or start supporting herself, she eventually decided to enroll at the Bureau of Educational Experiments’ Cooperative School for Student Teachers—more usually known as Bank Street, for its Greenwich Village location. There, the school’s founder Lucy Sprague Mitchell recruited her to collaborate on a series of textbooks in a style Mitchell called “Here-and-Now.”

At the time, children’s literature still consisted largely of fairy tales and fables. Sprague, basing her ideas on the relatively new science of psychology and on observations of how children themselves told stories, believed that preschoolers were primarily interested in their own small worlds, and that fantasy actually confused and alienated them. “It is only the blind eye of the adult that finds the familiar uninteresting,” Mitchell wrote. “The attempt to amuse children by presenting them with the strange, the bizarre, the unreal, is the unhappy result of this adult blindness.”

Under Sprague’s mentorship, Brown wrote about the familiar—animals, vehicles, bedtime rituals, the sounds of city and country—testing her stories on classrooms of young children. It was important not to talk down to them, she realized, and yet still to speak to them in their own language. That would mean summoning her own keen, childlike senses to observe the world as a child does—which is how one chilly November she found herself spending the night in a friend’s barn, listening to the rumbling of cows’ bellies and the purring of farm cats.

Maintaining a childlike perspective was the key to her work, but throughout her life, Brown worried that she had failed to grow up—even as she approached 40, she was painting glow-in-the-dark stars over the bed in her New York apartment. But like the wandering protagonist of one of her other classics, Home for a Bunny, she often felt out of place. “I am stuck in my childhood,” she told a friend, “and that raises the devil when one wants to move on.” The whimsical quality she interpreted as immaturity appealed to most of her friends, but it was a constant source of stress in her longest intimate relationship.

Brown met Michael Strange (born Blanche Oelrichs) at the home of a married man with whom they were each having an affair. Brown’s love life had always been complicated, and as she watched friends settle down with husbands and families, it was a fate she both yearned for and feared. But Strange, a poet who had been married to the actor John Barrymore, seemed to offer both the coziness of family life and the adventure Brown craved. Despite the era’s strong taboo around same-sex relationships, the women moved into apartments next door to one another and lived as a couple, on and off, through most of the 1940s.

Strange—alluring but also mercurial and narcissistic—was not an easy person to love. But even as she dismissed her partner’s “baby stories,” Brown was becoming a major force in the world of children’s publishing. Publishing dozens of titles a year under multiple names at seven publishers, she cultivated many of the best illustrators in the business and ensured that their work, an integral part of her books, was given its due at the printers. One of these was Goodnight Moon, for which she recruited her close friend Clement Hurd to provide the color-saturated paintings that have since become iconic. When it went on sale for $1.75 in the fall of 1947, the New York Times praised the combination of art and language, urging parents that the book “should prove very effective in the case of a too wide-awake youngster.”

Although she gave some of her earliest stories away for a pittance, Brown became a tough negotiator, once going so far as to mail her editor a set of dueling pistols. And as she matured, her stories grew past the simple “Here-and-Now” she had learned under Sprague, becoming more dreamlike and evocative. “The first great wonder at the world is big in me,” she wrote to Strange. “That is the real reason that I write”

Though she was grief-stricken after Strange died of leukemia in 1950, it was then that Brown fully came into her own, reconciling her disappointment at never being able to write “serious” work for adults with her success in the growing children’s publishing field (the Baby Boom had made baby books big business). Her new self-confidence led to a (thoroughly veiled) autobiography in picture book form, Mister Dog, about a pipe-smoking terrier who “belonged to himself” and “went wherever he wanted to go.”

“She was comfortable in her solitude,” Gary writes. “She belonged to herself and only herself.”

Soon after reconciling herself to life as a successful, independent woman, Brown met and fell in love with the man with whom she believed she would spend the rest of her life. James Stillman Rockefeller Jr., a handsome great-nephew of J.D. Rockefeller who was known to his friends as “Pebble,” asked her to marry him. For their honeymoon, the couple planned to sail around the world.

Before they could begin their grand adventure, Brown had to take a business trip to France, where she developed appendicitis. Her emergency surgery was successful, but the French doctor prescribed strict bed rest as she recovered. On the day scheduled for her release, a nurse asked how she felt. “Grand!” Brown declared, kicking up her feet—and dislodging a blood clot in her leg, which traveled to her brain and killed her within hours. She was 42.

Although he went on to find love and raise a family with another woman, Rockefeller never quite got over Brown. Gary, who relied on the now-elderly Pebble’s recollections for the last chapters of her biography, also persuaded him to write a moving prologue about their brief time together. “It has been sixty years since those days,” he writes, “but over half a century later, her light is burning ever brighter.”

It’s a sentiment with which any Goodnight Moon family is likely to agree.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)