The Swashbuckling History of Women Pirates

When women roamed the high seas in search of fortune, freedom, and sometimes revenge

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/bb/b9bb5163-d248-49af-ba3b-a912ed8daea9/erg0kx.jpg)

It started with a simple question: where were all the women pirates? Laura Sook Duncombe loved Peter Pan as a child and gobbled up every book on piracy she could find. But as she read, she was forced to face the harrrrrrd truth: All of the women seemed relegated to mere footnotes and short paragraphs sprinkled throughout books about male pirates. This curiosity spurred a quest for answers—and led to her new book Pirate Women: The Princesses, Prostitutes, and Privateers Who Ruled the Seven Seas.

Few historical figures ensnare the imagination in the same way as pirates do. The rum, the talking parrots, the hats and cloaks and treasure—all make for dramatic, theatrical tales. But Duncombe’s book does more than revel in the mystery and infamy of lady pirates: It contextualizes them, providing history and background on the societies they came from. Whether it’s the Moroccan pirate queen Sayyida al-Hurra (who terrorized the Mediterranean during the mid-16th-century) or Queen Elizabeth I’s woman sea dog, Lady Mary Killigrew, Duncombe separates the myths from the facts and considers the charm of a little-understood group of women.

“I wanted something to point at as incontrovertible truth that women are as much a part of pirate history as men,” Duncombe says. Smithsonian.com talked to the author about the challenges, opportunities and surprises that came with writing about the often-overlooked women of the sea.

Early in the book you say that no one has discovered a first-person account of pirating written by a female pirate, and that the stories are a combination of myth and fact. What challenges and opportunities did that present in your research and writing?

I really wanted to be as transparent as possible. I come from a legal background, so telling the truth is important to me. Pretty early on in the research, I realized there was no way I could in good conscience say “All of this happened exactly as I reported.” When the best research you have is something that everybody knows is as much fiction as fact, I thought it was important to say so.

Whether or not these women lived as these stories were told, these stories have endured over the centuries. Why these stories are being told the way they are and why people care about these stories says a lot about our culture and the culture these stories come from. But anybody who tells you they have a completely factual account of pirates is trying to sell you something.

Did anything surprise you in the research process?

How many layers some of these stories went through was surprising to me. Viking women stories were passed down orally and not recorded until later by Christian missionaries. The bias [the missionaries] had for maintaining order in the church and the family meant they were presenting ideal gender roles that were beneficial to the time period. It’s just the experience of wondering what these stories may have been like before they went through so many revisions. You wonder about the original intent in all of these pirate stories.

Once I started looking, it was apparent how many people had their hands on these stories and how much of history is recorded in a similar fashion. Even [when you’re present for an event], everybody’s got an agenda, even the people who try to present history as unbiased as possible. I don’t think there’s a 100 percent objective nature unless you point a video camera at something and just walk away. But even then, where do you put the camera?

You include St. Augustine’s story about Alexander the Great capturing a pirate and berating him for molesting the seas, to which the pirate replies, “How dare you molest the whole world? Because I do it with a small boat, I am called a pirate and a thief. You, with a great navy, molest the world and are called an emperor.” Can you talk about this idea of the sea as being a place owned by everyone and no one and why that might have been appealing to women?

Maritime law is still a separate branch of the law. Crimes committed on cruise ships are treated differently than crimes committed on terra firma. The idea of the sea being a place of opportunity unbounded by country is appealing. Countries who may have been allies up in Europe are now [on ships] in the Caribbean, and it’s a free for all. The shifting alliances led to an explosion of piracy because everybody was out for themselves. You don’t know where someone is from, you can fly a flag from a different country and pretend you’re someone you’re not. It’s a multinational masquerade ball.

For women this was appealing because they were able to more completely divest themselves of the repressive roles that they had been cast in in their own societies. They were able to make themselves anew.

Did women succeed in getting rid of those roles society had set for them?

Some women clearly did. You’ve got Cheng I Sao, who commanded a fleet larger than many of the legitimate fleets of her day. We have women who commanded male pirates and were astoundingly successful. This is where I bemoan the lack of primary sources: we don’t know how women felt when they were on the sea, with the wind in their hair. We don’t really know what their day-to-day life was like, if they found the peace and the freedom they were seeking.

But there’s something to the fact that we know women continued to do this over millennia. That siren song of the sea does continue to draw them to it and away from their home and their lives on the shore. Somehow women keep going to sea. It’s not a piece of cake to be a pirate, to be a sailor, but time after time after time, women weighed the pros and cons and did so.

Did women have to give up their femininity to be pirates?

Many of them dressed like women. They were not in disguise, so clearly they were able to maintain some semblance of outward femininity while aboard these ships. Grace O’Malley [an Irish pirate of the 16th century] gave birth to her youngest son on a pirate ship. I love this idea of, you’ve got a sword in one hand and you have a baby on your hip. Some of the pirates we’re told were very pretty, but we can only guess at how much they would’ve used their feminine wiles. A pretty face would not get you particularly far on a ship. I’m sure they had to keep up with the men because there’s not enough room on a ship for ornaments—but we only know about the ones who were caught. So there may have been scores of women who lived and died as men that we just don’t even know about.

You call Cheng I the most successful woman pirate of all time. Can you talk about her code of conduct and the way she surrendered, and how these things only amplified her success?

Lots of different pirates had codes of conduct that were observed on their ships. Cheng I is unique in her harshness of the penalties for the offenses and also the strict proscription of sexual activity, both consensual and nonconsensual, on- and off-board of the ship. [Raping female captives was punishable by death and even if captives had consensual sex they would still be killed.] There are some conflicting accounts of who actually wrote this code, whether or not it was her husband Chang Pao, but [the code] has been associated with her. It’s interesting when you think about women lawmakers, how men and women sometimes prioritize different things when they’re making the rules.

Her surrender is, to my knowledge, one of the only of its kind. She was the only one I can think of who was able to secure pensions for her crew. She was so terrifying that she basically forced the Chinese government to pay her to stop pirating.

She had to have been brilliant to do what she did. She married into a decent pirate operation but then expanded it beyond her late husband’s wildest dreams. I think her calculation [with the surrender] was, the government is expecting somebody coming to them with a phalanx of burly bodyguards armed to teeth. And she comes in with a bunch of ladies. That would’ve at the very least been very surprising and shifted the balance to power, and forced everyone to reconsider. She was incredibly successful in her negotiations, so it was a smart gambit.

You talk about pirates from the ancient Mediterranean all the way to modern times. Is there anything that unites all these women from different cultures and time periods?

They all had ships that were very different and methods that were very different. But I think they share the desire to control their own fates. And the desire for freedom from convention would unite all these women. Their hopes to escape the normal and be a part of something adventurous would tie all these women together. That’s part of what calls so many people to a love of piracy today. We share that desire for adventure. Not the desire for slitting throats and plundering the high seas, but one can empathize with the desire to have a say in how their lives go.

What do you want readers to come away from these stories with?

If someone comes away from this inspired to follow a path that they hadn’t felt bold enough to pursue before, I hope these women can be role models. Not in stealing, but going after your heart’s desire with everything you’ve got.

Do you have a favorite from all the women you wrote about?

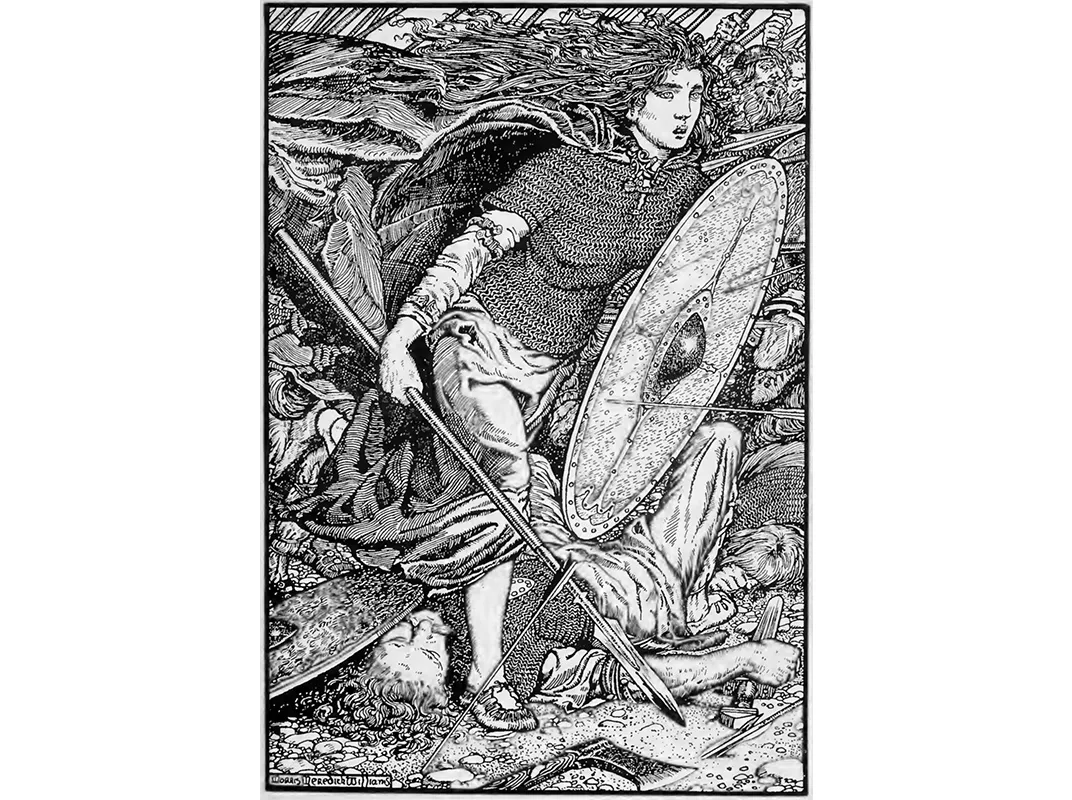

I say different pirates all the time because I love them all so much. I love Ladgerda, the Viking pirate who said it was better to rule without her husband and murdered him after rescuing him. His fleet was in distress after he left her for another woman. She sailed in to save the day but had a knife in her skirt and stabs him and says, ok I’m in charge now. I just think she’s cheeky.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)