Who Were America’s Enslaved? A New Database Humanizes the Names Behind the Numbers

The public website draws connections between existing datasets to piece together fragmentary narratives

:focal(400x285:401x286)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/81/bd81c143-a438-4dd8-8299-72e490a9de19/enslaved3.jpg)

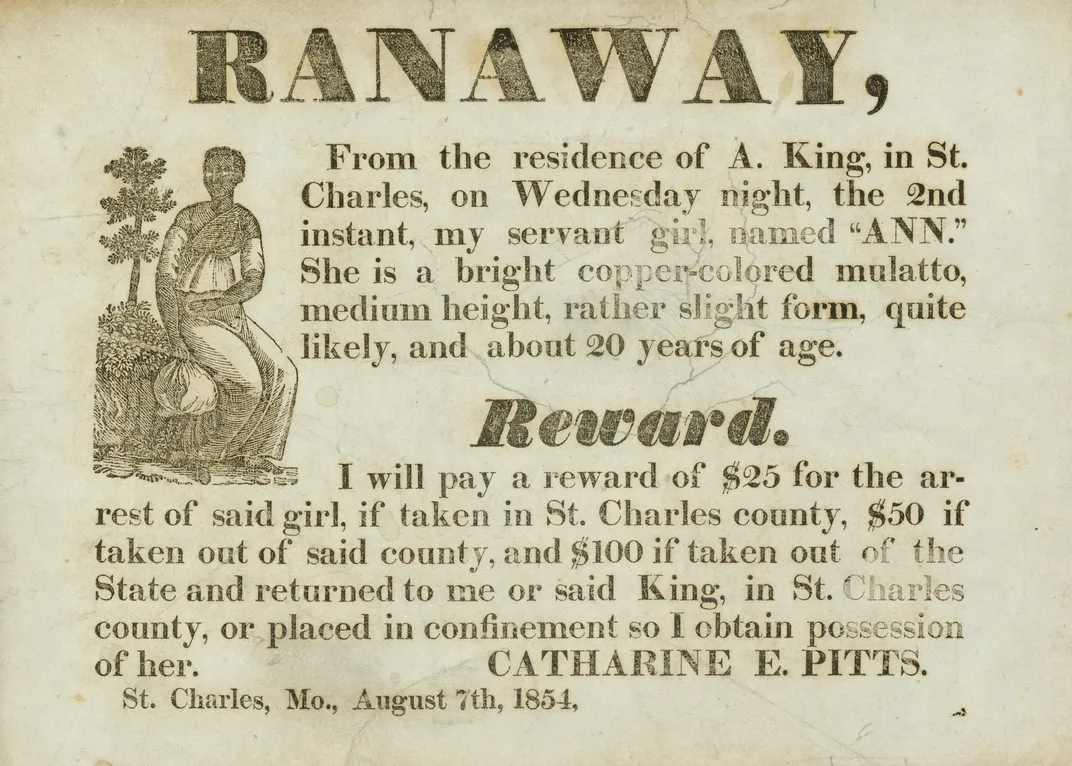

The night before Christmas in 1836, an enslaved man named Jim made final preparations for his escape. As his enslavers, the Roberts family of Charlotte County, Virginia, celebrated the holiday, Jim fled west to Kanawha County, where his wife’s enslaver, Joseph Friend, had recently moved. Two years had passed without Jim’s capture when Thomas Roberts published a runaway ad pledging $200 (around $5,600 today) for the 38- to 40-year-old’s return.

“Jim is … six feet or upwards high, tolerably spare made, dark complexion, has rather an unpleasant countenance,” wrote Roberts in the January 5, 1839, issue of the Richmond Enquirer. “[O]ne of his legs is smaller than the other, he limps a little as he walks—he is a good blacksmith, works with his left hand to the hammer.”

In his advertisement, Roberts admits that Jim may have obtained free papers, but beyond that, Jim’s fate, and that of his wife, is lost to history.

Fragments of stories like Jim’s—of lives lived under duress, in the framework of an inhumane system whose aftershocks continue to shape the United States—are scattered across archives, libraries, museums, historical societies, databases and countless other repositories, many of which remain uncatalogued and undigitized. All too often, scholars pick up loose threads like Jim’s, incomplete narratives that struggle to be sewn together despite the wealth of information available.

Enslaved: Peoples of the Historic Slave Trade, a newly launched digital database featuring 613,458 entries (and counting), seeks to streamline the research process by placing dozens of complex datasets in conversation with each other. If, for instance, a user searches for a woman whose transport to the Americas is documented in one database but whose later life is recorded in another, the portal can connect these details and synthesize them.

“We have these data sets, which have a lot of specific information taken in a particular way, [in] fragments,” says Daryle Williams, a historian at the University of Maryland and one of the project’s principal investigators. “... [If] you put enough fragments together and you put them together by name, by place, by chronology, you begin to have pieces of lives, which were lived in a whole way, even with the violence and the disruptions and the distortions of enslavement itself. We [can] begin then to construct or at least understand a narrative life.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/10/8a10d8ec-b6ee-4e7b-93d7-b09166dab41b/screen_shot_2020-12-10_at_100923_am.png)

Funded through a $1.5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Enslaved.org—described by its creators as a “linked open data platform” featuring information on people, events and places involved in the transatlantic slave trade—marks the culmination of almost ten years of work by Williams and fellow principal investigators Walter Hawthorne, a historian at Michigan State University, and Dean Rehberger, director of Michigan State’s Matrix Center for Digital Humanities & Social Sciences.

Originally, the team conceived Enslaved.org as a space to simply house these different datasets, from baptismal records to runaway ads, ship manifests, bills of sale and emancipation documents. But, as Rehberger explains, “It became a project about how we can get datasets to interact with one another so that you can draw broader conclusions about slavery. … We’re going in there and grabbing all that data and trying to make sense of it, not just give [users] a whole long list of things.”

The project’s first phase launched earlier this month with searchable data from seven partner portals, including Slave Voyages, the Louisiana Slave Database and Legacies of British Slave-Ownership. Another 30 databases will be added over the next year, and the team expects the site to continue to grow for years to come. Museums, libraries, archives, historical societies, genealogy groups and individuals alike are encouraged to submit relevant materials for review and potential inclusion.

***

To fulfill the “important obligation” of involving researchers of all types and education levels, the scholars made their platform “as familiar and unintimidating as possible,” according to Williams. Users who arrive without specific research goals in mind can explore records grouped by categories as ethnicity or age, browse 75 biographies of both prominent enslaved and free people and lesser-known ones, and visualize trends using a customizable dashboard. Researchers, amateur genealogists and curious members of the public, meanwhile, can use Enslaved.org to trace family histories, download peer-reviewed datasets, and craft narratives about some of the 12.5 million enslaved Africans transported to the New World between the 16th and 19th centuries.

At its core, says Rehberger, Enslaved.org is a “discovery tool. We want you to be able to find all these different records that have traditionally been out in these silos, and bring them together in the hope that people can then reconstruct what’s there.”

Mary N. Elliott, curator of American slavery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, emphasizes the project’s potential to help the public “understand [history] in more nuanced and personalized, humanized ways.” Reflecting on the creation of the museum’s “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition, she recalls, “One of the things that people said was ‘Oh, there’s only so much you can say about the lives of enslaved people during the early period. There’s nothing that they wrote.’” But as both Elliott and the team behind the web portal point out, archival records—when read correctly—can convey a strong sense of lived experiences.

Some of the sources featured in the database “have the enslaved person speaking, or at least someone writing down what they said, or something close to their physical presence,” Williams says. By weaving these threads of information together, he adds, contemporary observers can gain a sense of everything from enslaved people’s personal sentiments to how the official record may obscure the reality of their lived experiences.

Individuals looking for stories of their own family history may end up empty-handed (for now) but still come across records that inform their understanding of the brutal reality of enslavement. If, for instance, someone searching for their great-great uncle Harry comes across a runaway ad for Ned, an enslaved man who lived in the same area around the same time, they might dismiss it as unrelated. “But if you look at Ned’s story, you start to read the record, and you [see] that he has a scar over his eye. He ran away twice before,” Elliott says. “He’s probably running toward his loved ones. … It tells you about how he had the ability to run away twice. And is this plantation near the one my family was enslaved at? And I wonder where he got that scar.”

For people to “read the record, in a way that they understand the humanity of African Americans under the most inhumane circumstances,” is key, the curator continues. “You’re not reading it for the sake of reading. You’re really connecting with this … man who [had] something traumatic happen to him within the framework of slavery.”

***

Enslaved.org traces its origins to the 2000s, when Hawthorne was researching a book on the flow of enslaved people from two ports in West Africa. Drawing on an archive of Brazilian state inventories, which listed enslaved Africans as property whose value was based on factors such as age and skills, he created a database with demographic information on some 9,000 individuals. This broad swath of data allowed the historian to run statistical analyses about patterns of enslavement, including “Where were people coming from? … Can I zero it down to a particular place? What … were they bringing with them across the ocean? What foods did they eat? How did they worship?”

Hawthorne adds, “You begin to see people coming [to the Americas] not as generalized Africans, … but as Balanta, as Mandinka, as Fulani, as Hausa, people who come with specific cultural assumptions, with specific religious beliefs. What did they preserve from the place [where] they came? What did they have to abandon based on the conditions in the Americas?”

In 2010, Hawthorne partnered with Rehberger and historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, who had created a similar portal featuring 107,000 records of enslaved individuals in Louisiana, to build a digital repository for both datasets. Funded through a $99,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the resulting project, Slave Biographies: The Atlantic Database Network, laid the groundwork for Enslaved.org, a site capable of not only housing dozens of datasets but also placing them in interaction with each other.

A decade ago, computing technology hadn’t advanced enough to interpret data on the scale used by Enslaved.org. Today, however, researchers can use semantic triples—three-part sentences that “define a particular moment,” like “Maria was baptized in 1833” or “Maria got married in 1855,” according to Rehberger—to create vast “triplestores” filled with linked information. Here, the site can parse out Maria, the religious rite (baptism or marriage), and the year as three distinct bits of data.

“I often think of … ripping apart the dataset into little bits and pieces of paper, and then taking a thread and trying to thread and bring them back together again,” Rehberger says. “That, in a sense, is what we’re trying to do.”

***

As Hawthorne notes, the team is still “in the early days of our project,” If an individual enters their family name in the search bar in the near future, they likely won’t find anything. “It’s possible that you will,” he adds, “but certainly as this project grows and expands, as more and more scholars and members of the public contribute, those possibilities [open] up.”

Enslaved.org welcomes data compiled by the public, but Williams emphasizes that the researchers aren’t “exactly crowdsourcing.” All submissions will undergo two levels of review; scholars can also submit their datasets to the portal’s peer-reviewed Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation. Another option for individuals with an interest in unearthing these kinds of hidden histories is to volunteer at local historical associations and museums, which can then collaborate directly with the Enslaved.org team.

The project’s launch earlier this month arrives at a pivotal point in the nation’s history. “We’re in a moment right now, of interest in slavery and slave histories and slave names, slave biographies,” Williams says. “It’s also a social and racial justice moment, … a family history, genealogy curiosity moment.”

One of Enslaved.org’s strengths, says Elliott, is its ability to map current events onto the past. Though the database’s focus is enslaved people, it also contains information on enslavers and individuals who participated in the historical slave trade. Slavery involved “all these different actors,” the curator explains. “And that’s vastly important, because it’s so easy for people to segregate this history. But … you cannot look at a bill of sale and [say] it’s only a black person on that document. Guess who signed it? The seller and the purchaser. [And] there’s a witness.”

By focusing on individuals rather than the overwhelming—and often unfathomable—numbers that tend to dominate discussions of slavery, the team hopes to restore once-anonymous figures’ identities and deepen the public’s understanding of the transatlantic slave trade.

“There’s a lot of power to reading about individuals as opposed to populations of people,” Hawthorne says. “If you look through the datasets, every single entry is a named individual. And there’s a lot of power to that, to thinking about Atlantic slavery, slavery in the American South, as being about individuals, about individual struggles under this incredibly violent institution.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/03/25/03258971-cb46-4ce4-9775-75c743057590/nmaahc-2018_43_2_001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/90/8e9062ca-4c30-4844-a898-c40ef1693668/runaway_slave_reward_broadside_maryland_1802.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)