Team Hollywood’s Secret Weapons System

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120523113035Hedy-Lamarr-web.jpg)

By the start of World War II, they were two of the most accomplished talents in Hollywood. Leading lady Hedy Lamarr was known as “the most beautiful woman in the world,” and composer George Antheil had earned a reputation as “the bad boy of music.” What brought them together in 1940 was that timeless urge to preserve one’s youth and enhance one’s natural beauty, but what emerged from their work was a secret communications system that Lamarr and Antheil hoped would defeat the Nazis.

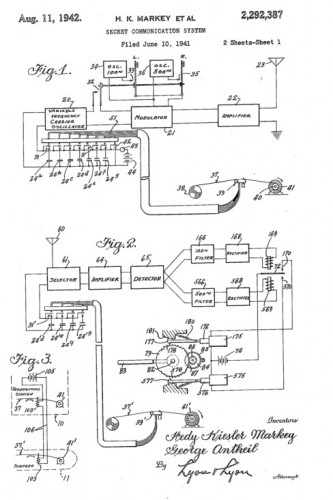

It didn’t work out that way: The patent they received—No. 2292387—simply gathered dust in the U.S. Patent Office until it expired in 1959. But three years later, the U.S. military put their concept to use during the Cuban Missile Crisis. And ultimately, the two unlikely pioneers’ work on “frequency hopping” would be recognized as a precursor to the “spread-spectrum” wireless communications used in cellular phones, global positioning systems and Wi-Fi technology today.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1913, in Vienna; her father was a well-to-do Jewish banker and her mother was a concert pianist. Sent to finishing school in Switzerland, she grew into a strikingly beautiful teen and began making small German and Austrian films. In 1932, she starred in the Czechoslovakian film Ecstasy—which was quickly banned in Austria for the starlet’s nudity and for a scene in which her facial expressions, in closeup, suggested that she was experiencing something akin to the film’s title.

In 1933, she married Friedrich Mandl, a wealthy Jewish arms manufacturer 13 years her senior who converted to Catholicism so he could do business with Nazi industrialists and other fascist regimes. Mandl hosted grand parties at the couple’s home, where, she would later note, both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini were guests. Lamarr would later claim that Mandl kept her virtually locked away in their castle home, only bringing her to business meetings because of her skill at mathematics. In these meetings, she said, she learned about military and radio technologies. After four years of marriage, Lamarr escaped Austria and fled to Paris, where she obtained a divorce and eventually met Louis B. Mayer, the American film producer with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Mayer signed the young Austrian beauty and helped her find the screen name Hedy Lamarr. She immediately began starring in films such as Algiers, Boom Town and White Cargo, cast opposite the biggest actors of the day, including Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and John Garfield. MGM was in what became known as its Golden Age, and Mayer promoted Lamarr as “the most beautiful woman in the world.”

Yet despite her unquestionable beauty, Lamarr thought there was room for improvement. At a dinner party in Hollywood, she met George Antheil, a dashing and diminutive composer renowned in both classical and avant-garde music. Born in 1900 and raised in Trenton, New Jersey, Antheil had been a child prodigy. After studying piano both in the United States and Europe, he spent the early 1920s in Paris, where he counted Ezra Pound, James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway as friends.

By the mid-1930s, Antheil had landed in Hollywood, composing dozens of scores for some of the great filmmakers of the time, including Cecil B. DeMille. He’d also written a mystery novel, Death in the Dark, as well as a series of articles for Esquire magazine. In one of those articles, “The Glandbook for the Questing Male,” he wrote that a woman’s healthy pituitary gland might enhance the size and shape of her breasts. Lamarr was taken with the idea, and after meeting Antheil, she went to him for advice on enlarging her bust without surgery, Richard Rhodes writes in his recent book, Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World.

At some point, their conversation veered from breast enlargement to torpedoes, and the use of radio control to guide them toward their targets. (At the time, torpedoes were generally free-running devices.) Clearly, Lamarr had gained some understanding of weaponry during her first marriage. She was aware that radio transmission on one frequency could be easily jammed or intercepted—but she reasoned that if homing signals could be sent over multiple radio frequencies between the transmitter and the receiver, the enemy would perceive them only as a random series of blips on any one frequency. The actress had envisioned a system of “frequency hopping.” The challenge was how to synchronize the pattern of frequencies between transmitter and receiver.

Anthiel was no stranger to weaponry himself; he had worked as a United States munitions inspector. Moreover, he had written Ballet Mecanique, which called for the synchronization of 16 player pianos. With radio signals hopping about different frequencies like notes on a piano, Lamarr and Anthiel believed they could create a jam-proof homing system for torpedoes. Their system involved two motor-driven rolls, like those on a player piano, installed in the transmitter and aboard the torpedo and synchronized through 88 frequencies—matching the number of keys on a piano.

Consulting with an electrical engineering professor at the California Institute of Technology, the two inventors worked out the details of their invention in their spare time. Antheil continued to compose film scores, and Lamarr, at 26, was acting in Ziegfeld Girl alongside Jimmy Stewart and Judy Garland. They submitted their patent proposal for a “Secret Communication System” in 1941, and that October the New York Times reported that Lamarr (using her married name at the time, Hedy Kiesler Markey) had invented a device that was so “red hot” and vital to national defense “that government officials will not allow publication of its details,” only that it was related to “remote control of apparatus employed in warfare.”

After they were awarded their patent on August 11, 1942, they donated it to the U.S. Navy—a patriotic gesture to help win the war. But Navy researchers, believing that a piano-like mechanism would be too cumbersome to install in a torpedo, didn’t take their frequency-hopping concept very seriously. Instead, Lamarr was encouraged to support the war effort by helping to sell war bonds, and she did: Under an arrangement in which she would kiss anyone who purchased $25,000 worth of bonds, she sold $7 million worth in one night.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that engineers from Sylvania Electronics Systems Division began experimenting with ideas documented in Lamarr and Antheil’s system. Instead of a mechanical device for frequency-hopping, engineers developed electronic means for use in the spread-spectrum technology deployed during the U.S. naval blockade of Cuba in 1962. By then, Lamarr and Antheil’s patent had expired and he had died of a heart attack.

It is impossible to know exactly how much Lamarr and Antheil’s invention influenced the development of the spread-spectrum technology that forms the backbone of wireless communications today. What can be said is that the actress and the composer never received a dime from their patent, they had developed an idea that was ahead of its time.

Later years would not be so kind to Hedy Lamarr. “Any girl can be glamorous,” she once said. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.” She was married and divorced six times, and as movie offers began to dwindle, her finances did, too. She was arrested in 1966 for shoplifting at a Los Angeles department store. She had plastic surgery that her son, Anthony Loder, said left her looking like “a Frankenstein.” She became angry, reclusive and litigious. She once sued Mel Brooks and the producers of Blazing Saddles for naming a character in that film “Hedley Lamarr,” and she sued the Corel Corporation for using an image of her on its software packaging. Both suits were settled out of court. She ended up living in a modest house in Orlando, Florida, where she died in 2000, at the age of 86.

Hedy Lamarr has a star on the Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, but in 1998, she received an award uncommon for stars of the silver screen. The Electronic Frontier Foundation named her and George Antheil the winners of that year’s Pioneer Award, recognizing their “significant and influential contributions to the development of computer-based communications.”

“It’s about time,” she was reported to have said.

Sources

Books: Richard Rhodes, Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World, Doubleday, 2011. Hedy Lamarr, Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman, Fawcett, 1967. Asoke K. Talukder, Hasan Ahmed, Roopa R. Yavagal, Mobile Computing: Technology, Applications and Service Creation, Tata McGraw Hill, 2010. Steve Silverman, Einstein’s Refrigerator and Other Stories From the Flip Side of History, Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2001. Rob Walters, Spread Spectrum: Hedy Lamarr and the Mobile Phone,” ebook published by Satin via Rob’s Book Shop, 2010. Stephen Michael Shearer, Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr, Macmillan ebook, 2010.

Articles: “Hedy Lamarr Inventor,” New York Times, October 1, 1941. “Hop, Skip and a Jump: Remembering Hedy Lamar” (sic) by Jennifer Ouelette, Scientific American, January 9, 2012. “From Film Star to Frequency-Hopping Inventor,” by Donald Christiansen, Today’s Engineer, April, 2012, http://www.todaysengineer.org/2012/Apr/backscatter.asp “Secret Communications System: The Fascinating Story of the Lamarr/Antheil Spread-Spectrum Patent,” by Chris Beaumont, http://people.seas.harvard.edu/~jones/cscie129/nu_lectures/lecture7/hedy/pat2/index.html “The Birth of Spread Spectrum,” by Anna Couey, http://people.seas.harvard.edu/~jones/cscie129/nu_lectures/lecture7/hedy/lemarr.htm “Hedy Lamarr Biography: Hedy’s Folly by Richard Rhodes (Review), by Liesl Schillinger, The Daily Beast, November 21, 2011. “Glamour and Munitions: A Screen Siren’s Wartime Ingenuity,” by Dwight Garner, New York Times, December 13, 2011. “Unlikely Characters,” by Terry K., http://terry-kidd.blogspot.com/2009_10_01_archive.html “Mechanical Dreams Come True,” by Anthony Tommasini, New York Times, June 9, 2008. “Secret Communication System, Patent 2,292,387, United States Patent Office, http://www.google.com/patents?id=R4BYAAAAEBAJ&printsec=abstract&zoom=4#v=onepage&q&f=false

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)