It ranks as one of the greatest feats of exploration in modern times. For five months, beginning in mid-December 1913, a team composed at its peak of more than 100 men, Brazilian and American, made its way across South America’s great heartland, by land and on rivers, on foot and by horse, mule, truck, steamboat, barge, launch and canoe, moving supplies, pack animals and boats across more than 2,500 miles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/27/99278785-e32e-411e-bf04-316d60d277c0/aprmay2023_d05_amazon.jpg)

Two men of markedly different backgrounds led this extraordinary undertaking. Theodore Roosevelt, only a few years removed from the American presidency, was among the world’s most celebrated figures. But throughout the time he was in the wilderness, he mostly deferred to his more experienced Brazilian counterpart, a 48-year-old Brazilian Army colonel named Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon.

By any measure—number of expeditions, distances traversed, degree of difficulty, information gathered—Rondon is the greatest explorer of the tropics in recorded history, with a list of accomplishments that eclipses those of better-known figures such as Henry Stanley or Richard Francis Burton. All told, he participated in more than a dozen expeditions through Brazil’s northern wilderness, surveying his country’s hitherto-unknown territory, mapping its borders, building roads and bridges, founding settlements, and making the initial, peaceful contact with dozens of Indigenous groups.

That Rondon himself was Indigenous, an orphan from the state of Mato Grosso (“dense jungle” in Portuguese) who rose to become a marshal of the Brazilian Army and spoke four European and six Indigenous languages fluently, made him as comfortable in the cafés of Rio de Janeiro as in the remotest corners of the Amazon, able to move easily between the worlds of science and shamanism.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8e/c0/8ec02d77-c181-49e0-b927-55caf787fc93/aprmay2023_d04_amazon.jpg)

Trained as an astronomer and engineer, Rondon was devoted to promoting scientific awareness of the Amazon and its peoples. A national commission bearing his name published more than 100 scientific papers, in disciplines as varied as anthropology, astronomy, biology, botany, ecology, ethnology, geology, herpetology, ichthyology, linguistics, meteorology, mineralogy, ornithology and zoology. Scientists under Rondon’s direction discovered and cataloged scores of new animal, plant and mineral species. Many of his own scientific papers documented the languages of Indigenous peoples or sought to explain their cultures, cosmology, rites, social structure and religion.

As the founder, in 1910, of the Brazilian government’s Indian Protection Service, or SPI, which he led for decades afterward, he fought to defend Brazil’s Native peoples from the ranchers, miners, loggers and rubber tappers who coveted their land, and he battled the intellectual and political leaders openly calling for their extermination on “scientific” grounds.

On his own expeditions, Rondon adhered to a policy of absolute nonviolence in his dealings with tribal groups, many of them previously uncontacted: The SPI’s motto was “Die if you must, but kill never.” As early as 1925, Albert Einstein, astonished during a visit to Brazil by the man the press called the “pacifist general,” nominated Rondon for the Nobel Peace Prize, and when Rondon died, the International Red Cross saluted him as an apostle of nonviolence whose life and work, “like that of Gandhi,” constituted a victory for “the forces of peace.”

Rondon’s construction of a telegraph line across Brazil’s vast, rugged interior, often with the assistance of local Indigenous groups, played a central role in the country’s transition from a haphazardly organized empire to a modern republic, and it resonates to this day in the country’s psyche as a feat of national integration in the way the transcontinental railroad was celebrated in the United States.

Thus when Roosevelt, restless for an adventure after an unsuccessful 1912 bid for a third presidential term, made contact with Brazilian authorities about planning an expedition into the uncharted forest, there was no question within Brazil’s government who would guide him. In his memoirs, Rondon wrote that he agreed to take Roosevelt through the Amazon only “under the condition that the expedition not limit its activities to a series of excursions to hunt for big game,” and that serious scientific work be undertaken.

Of the five itineraries Rondon proposed, the most ambitious was to descend the Rio da Dúvida—the River of Doubt—which he had first encountered during an expedition in 1909 and had yearned to explore ever since. No one knew how long the river was, nor the kind of terrain through which it flowed, much less where its waters discharged—hence its provisional name.

Roosevelt promptly chose the itinerary that, in Rondon’s understated assessment, “offered the greatest number of unforeseen difficulties.” A descent of the river, Roosevelt wrote, “could be made of much scientific value,” and with it “a substantial addition could be made to … geographical knowledge.”

What Rondon proposed was exploration in its purest, most challenging form. The principal focus would be cartography, with the work to be carried out in terrain utterly unknown to either science or geography.

When friends at the American Museum of Natural History urgently wrote Roosevelt in Brazil to warn him off the plan before he set out for the jungle, he responded coolly, “I have already lived and enjoyed as much of life as any nine other men I know. I have had my full share, and if it is necessary for me to leave my bones in South America, I am quite ready to do so.”

The river descent itself began on Friday, February 27, 1914, following a grueling two-and-a-half-month trek through the Pantanal, Brazil’s vast inland swamp, and across the Mato Grosso plateau. Breakfast was jerky, hardtack and coffee. Then the last supplies were loaded onto the canoes. “One was small, one was cranky, and two were old, waterlogged and leaky,” Roosevelt wrote. “The other three were good.”

The smallest, most maneuverable dugout was first in line, carrying Roosevelt’s 24-year-old son, Kermit, who had volunteered as lookout, and two skilled paddlers named João and Simplício. Kermit had been in Brazil since graduating from Harvard in 1912, working as an engineer, supervising the construction of railroads, trestles and bridges. Rondon and Lieutenant João Salustiano Lyra, his second in command, followed in the next boat. Roosevelt—who for security reasons had the expedition’s doctor, José Antônio Cajazeira, constantly at his side—was assigned with George Cherrie, an American naturalist, to the last and largest of the canoes, a 25-footer weighing more than a ton, and given three paddlers. Sandwiched between Rondon’s and Roosevelt’s canoes were two jury-rigged rafts loaded with cargo, each assigned four boatmen.

To the Brazilians, there was nothing unusual about the 16 camaradas, the “comrades” who paddled and performed the most demanding tasks while descending the river. Like Rondon, they were individuals of mixed European, Indigenous and African ancestry and also tough backwoodsmen. But the Americans were amazed by the uncomplaining durability of the men, most of whom went about without shoes or shirts, slept in randomly strung hammocks, and worked long hours with little food. “They were expert river-men and men of the forest, skilled veterans in wilderness work,” Roosevelt wrote. “They were equally at home with pole and paddle, with ax and machete.” They were also “hard-working, willing and cheerful,” he continued. “Good men around camp.”

The first day passed uneventfully as Rondon and Lyra began to map the upper reaches of the River of Doubt. Such work would be quick and easy today. But a century ago, without GPS or even meaningful aerial mapping, Rondon and his men did everything manually, by compass and solar observation, using an onerous method known as “fixed position” sighting. When an appropriate location was found, the spotter jumped ashore, cleared away brush with his machete and raised a red-and-white sighting pole until surveyors in a separate boat measured the angle and distance between their position and the sighting rod. Then the spotter would hop back into his canoe, and the process would be repeated at the next stop.

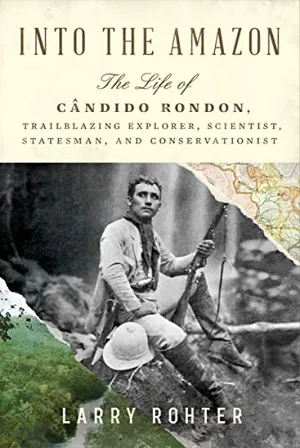

Into the Amazon: The Life of Cândido Rondon, Trailblazing Explorer, Scientist, Statesman, and Conservationist

A thrilling biography of the Indigenous Brazilian explorer, scientist, statesman, and conservationist who guided Theodore Roosevelt on his journey down the River of Doubt.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6a/93/6a9344fe-b071-4a98-a2fb-fbb8d5ce956a/aprmay2023_d07_amazon.jpg)

Rondon, in the second canoe, meticulously recorded measurements into notebooks custom-made in Rio de Janeiro. Lyra used a state-of-the-art theodolite, a precision instrument that computes angles in both the horizontal and vertical planes, and Rondon had a compass and a barometer to gauge the river’s altitude above sea level.

But making frequent stops to calculate position soon grew exhausting: Rondon’s field journal indicates that the expedition halted 114 times that first day, barely advancing seven miles. The River of Doubt was a puzzling and unpredictable stream, twisting and turning in every direction. Rondon’s logs from that first afternoon show that at one time or another the river’s course flowed in the direction of each of the four cardinal points of the compass.

Rondon was pleased, though, at how the trip had begun. “We obtained an abundant supply of game,” he wrote. “In addition to game birds, we retrieved honey; it was jubilation when we came across a milk tree, a giant of the forest called that because of the thick white liquid that oozed from any cut made in its bark and which the camaradas drank avidly.”

The next day they made nearly 100 stops to measure location. A routine was shaping up—one that would underscore the often conflicting goals of the American and Brazilian expedition members, generating tensions that would persist throughout the descent.

Roosevelt wanted to get down the river as rapidly as possible, reach Manaus and travel home. He was still a public man, with political aspirations, and during the time he had been in South America he had watched anxiously as the global situation deteriorated (which would soon lead to the outbreak of the First World War). Unable to voice his opinions from afar, he was impatient to leap back into the fray.

Kermit was equally restless. He had recently become engaged to Belle Willard, the Virginia-bred daughter of the U.S. ambassador to Spain, and was obsessed with reuniting with her. His diary was filled with musings about her and dreams of their future together, and he carried her letters to him in a pouch around his neck so that they would not be lost.

Rondon, by contrast, had waited nearly five years to return to the river he had discovered, and he intended to exploit this opportunity to explore it. He had forewarned Roosevelt himself that this would not be a safari but a bona fide scientific expedition, and he expected every member to do his part.

The men faced their first big challenge on the afternoon of March 2. The river suddenly accelerated, and they found themselves bouncing through rapids, with water foaming angrily ahead. The paddlers quickly pulled off to the right bank, secured the canoes and set up camp, while a scouting party hacked their way through the brush to reconnoiter.

What they discovered gave everyone pause. For half a mile, the river bounded downward through a series of boiling rapids, which were broken by a pair of waterfalls six feet high. Then it narrowed dramatically and surged through a jagged sandstone gorge. “It seemed extraordinary, almost impossible,” Roosevelt wrote, “that so broad a river could in so short a space of time contract its dimensions to the width of the strangled channel through which it now poured its entire volume.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d3/e2/d3e2447a-843d-43ef-8cda-ab04f22392fd/aprmay2023_d99_amazon.jpg)

It took an entire day to tote food crates, tents, duffel bags and scientific equipment to a new campsite below the rapids. Rondon exempted from that task one ailing paddler and Kermit, who had developed a painful case of boils on his thighs, but both of the expedition’s commanders joined the others in transporting the gear. Early the next morning, Lyra and a party of camaradas headed into the forest with axes and machetes to fell dozens of trees and cut their trunks into rounded logs. They placed these along a portage trail evidently used by local Indians, thereby creating a skidway along which they could drag the canoes. Meanwhile, another team heaved the empty dugouts from the riverbank, to be pulled along the skidway one by one.

This was backbreaking work, magnified in difficulty by the insects that swarmed, bit and stung. A pair of camaradas was stationed in front of each of the canoes, each connected to the boat by a drag rope fastened around his torso. A third stood behind with a pole, which he used to guide the canoe as it clumsily slid down the uneven log path. Several dugouts slammed into sandstone ledges to the left; at least one was split badly. Still another made it all the way down the trail only to slip free of the ropes and, as it was lowered back into the water, sink to the bottom; it was retrieved with strenuous effort by the exhausted camaradas.

The expedition resumed its journey at midday on March 5. The next day, though, the explorers encountered more rapids and were forced to steer to the riverbank. A scouting party discovered that some 400 yards downstream the river smashed into a line of giant boulders, impeding all passage, followed by at least a mile of rapids and a pair of waterfalls about 100 yards apart. Another portage awaited, even longer and more difficult than the first.

“We had no idea how much time the trip would take,” Roosevelt would write. “We had entered a land of unknown possibilities.”

On March 15, as the first two canoes rounded a bend in the river, the stream widened, dividing into two sets of roiling rapids separated by an island. Rondon, sensing trouble, ordered his dugout to pull to the side and called to Kermit’s canoe to do the same. But Kermit either did not hear Rondon or chose to ignore his command. The lead canoe plunged forward, heading directly for the island.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6e/5d/6e5dd27c-8e74-4d8c-aaeb-270c59b94d73/aprmay2023_d02_amazon.jpg)

Now all three men, tossed into the foaming water, were battling for their lives. João grabbed for the towline and swam for shore but could not maintain his hold on the rope. Kermit managed to climb onto the keel of the overturned canoe and ride it, like a bull at a rodeo, through a second set of rapids before being thrown off. Desperate and exhausted, his waterlogged clothing weighing him down, he swam for shore, where he could only cling to a branch until he had recovered his breath.

Kermit was back on land, walking to find the others, when Rondon and Lyra encountered him on the trail. “Well, you have had quite a splendid bath, eh?” Rondon said to the younger Roosevelt. There is no way to know if his tone was sarcastic, in reproach to what he perceived as Kermit’s youthful heedlessness, or whether he was making a sympathetic joke, relieved that the son of his eminent guest had not perished. But where were João and Simplício?

João showed up not long after, having swum back across the river. But there was no sign of Simplício. In addition, the canoe was lost, along with the supplies in it. Devastated, Kermit set out on his own to search for Simplício. He walked for several miles but recovered only one paddle and a single food tin. Simplício’s body was never found.

In his diary, Kermit was guarded about his boatman’s death, writing only, “Simplício was drowned.” For his part, Roosevelt portrayed the disaster as simply an accident of fate. In a private conversation with Rondon, though, João said that Kermit had heard Rondon’s command to stop but decided to see if they could run the rapids to the island’s right and ordered the boatmen ahead.

With no body to bury, Rondon had the men erect a memorial cross reading “Here perished the unfortunate Simplício” at the edge of the rapids. He also named the falls in Simplício’s honor, and they appear as such on Brazilian maps even today.

In every account of the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition over the past century, Brazilian or American, Simplício has always been identified merely by his first name or as “poor Simplício.” But in Rondon’s records is Simplício’s complete name: Antônio Simplício da Silva.

Another exhausting portage began amid sheets of rain. While the camaradas felled trees for a skidway, cleared brush and hauled the canoes from the river, Rondon and his favorite dog, Lobo, headed down a jungle path to do reconnaissance and, with any luck, shoot a game bird or a monkey for meat. But half a mile from camp, a peculiar howling echoed through the forest—almost, but not exactly, like that of a spider monkey, the largest simian in the jungle and an excellent source of meat.

Lobo instinctively bounded ahead as Rondon peered into the canopy, his rifle at the ready. Within seconds, though, he heard his dog yelping, first in surprise, then in pain.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/47/15472d9a-a7ad-4e70-80ac-0923ff1c19c9/aprmay2023_d06_amazon.jpg)

He advanced cautiously, registering unwelcome human sounds: “short exclamations, energetic and repeated in a kind of chorus with a certain cadence” that he had heard before only when Indigenous war parties were “ready to commence the attack.” He fired a single warning shot in the air, “overcoming my initial impulse to run and defend Lobo,” then hurried back to camp.

Rondon’s immediate concern was an ambush. He dispatched Cherrie to warn the camaradas upstream, asked Roosevelt to mount guard at the end of the portage, and with Kermit, Lyra and the Indigenous scout Antônio Paresi accompanying him returned to the trail in search of Lobo. When they reached the dog, it was already dead—pierced by a pair of poison-tinged arrows whose design was unfamiliar to Rondon and Paresi. Before returning to the site of the ambush, Rondon had grabbed several ax heads and stuffed his pockets with colored beads—presents for what he assumed was a hunting party frightened by his approach.

He buried Lobo next to a basket full of animal entrails the Indians had brought as bait, probably for fishing, but abandoned as they fled. Around Lobo’s grave Rondon arrayed his gifts, to signal to the Indigenous group—likely members of the people known as the Cinta Larga, whose relations with the outside world continue to be tense and even violent into the 21st century—that his intentions remained peaceful.

Rondon had been lucky, and he knew it. “I thought, mournfully contemplating my dead companion, that perhaps he had given his life for mine.”

The explorers were now down to four canoes, simply not enough to carry 21 men and their equipment. To continue, the canoes would have to be lashed together to form a pair of rafts, each with three paddlers and one principal aboard, and loaded with as much equipment as they could support. The remaining equipment would have to be discarded, and the rest of the men would hack their way along the overgrown riverbank until they reached a new campsite, alert to any sign of an Indian attack.

The men navigated two sets of rapids that way. At the other end, Rondon and Kermit encountered a deep river some 70 feet wide gushing into the River of Doubt from the west. This was a significant discovery: It meant the River of Doubt itself did not flow west from here, but rather likely flowed northward for hundreds of miles—eventually disgorging into the Madeira River, the Amazon’s largest tributary, as Rondon had guessed.

The Cinta Larga no longer bothered to keep their surveillance secret and waged an unrelenting campaign of intimidation. Though concealed in the jungle, they were very close, for the dogs were constantly barking at some unseen presence. As the explorers hewed to a narrow path along the riverbank, they saw fresh footprints in the mud that were not their own, and they heard rustling in the bush just beyond. “The footprints, the abandoned camps, and the voices of unseen people became uncanny,” Cherrie wrote.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/96/79969e17-dfa7-4c05-a3fd-08be149b8e84/aprmay2023_d08_amazon.jpg)

Yet Rondon halted the expedition at a bend in the river when he noticed an abundance of araputanga trees—easy to carve, resistant to rot, light in weight and buoyant in water, and thus advantageous for making desperately needed canoes. Roosevelt objected, but Rondon reassured him by mounting a nightlong guard for the first time; he himself awoke at 2 a.m. to make sure the lookouts hadn’t fallen asleep.

Two days later, the replacement canoes were finished. But now various health problems were beginning to emerge among the overtaxed boatmen. “We were crossing enemy territory, tormented by mosquitoes and ants,” Rondon wrote. “The camaradas who didn’t want to wear shoes had feet that were now so swollen that they could barely carry on. Cajazeira tried to relieve everyone’s suffering and maintain in good condition the health of everyone in the expedition, but there were already two cases of fever.”

The Americans were increasingly worried. “Our position is really a very serious one,” Cherrie wrote in his diary. “Provisions are every day decreasing. It is impossible to go back. The journey ahead is undoubtedly a very long one.” He concluded the entry on a fatalistic note: “It is very doubtful if all our party ever reaches Manaus.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1d/88/1d88e334-72a1-4cfa-8f6d-fdddb6222219/aprmay2023_d09_amazon.jpg)

On March 22, Roosevelt challenged Rondon about how the exploration work was being carried out. “Kermit was extremely lucky to escape alive from the accident in which Simplício perished,” he told Rondon, according to the only surviving account of the conversation, from Rondon’s diary. “I simply cannot tolerate seeing my son’s life threatened at every turn by the presence of the Indians, threatened more so than any other member of the expedition, since he is in the lead canoe.” Roosevelt also questioned Rondon’s insistence on cartographic precision, which he felt slowed them down. “Great men don’t concern themselves with minor details,” he said.

“I am neither a great man, nor is this a minor detail,” Rondon responded. “Mapping the river is indispensable, and without it the expedition, as far as I am concerned, will have been entirely pointless.”

But Rondon agreed to abandon the fixed-position method of mapping, which would mean fewer stops, in favor of a less precise method calculated from a pair of canoes in motion. He also acquiesced to one of Roosevelt’s demands: “Kermit will no longer go in front.”

They’d been on the river exactly a month when, maneuvering a pair of dugout canoes through a set of narrow rapids, several camaradas lost their hold on the boats, which rammed into rocks and began to sink.

Responding to shouts for help, Roosevelt jumped into the water and, chest-deep in the turbulent stream, joined the men in “straining and lifting to their uttermost.” He gashed a shin badly on a jagged rock. Blood began to spurt from the wound.

At camp, Roosevelt tried to play down the severity of the injury, which he attributed to “my own clumsiness.” Cajazeira dressed the wound with antiseptic and wrapped it in gauze. Roosevelt stayed off his feet for two days, but then, walking downriver to the next campsite, he was forced to pause repeatedly because of the pain. Upon arriving, Roosevelt “lay flat down on the damp earth for some time before recovering,” Cherrie wrote. Not only did Roosevelt’s wound become infected, but soon it was clear he was also suffering attacks of malaria. His temperature soared to 105 degrees, and he slipped into delirium.

One night, just before dawn, Cherrie heard Roosevelt call his name, and he rushed to his side. Kermit was already there. “Boys, I realize that some of us are not going to finish this journey,” Roosevelt said. Looking squarely at Cherrie, he went on, “I want you and Kermit to go on. You can get out. I will stop here.”

Roosevelt’s deteriorating health was only one of many menacing problems. Their supply of food depleted, the men’s physical performance was diminishing—increasing the likelihood of accidents—as was their morale.

Even Rondon, ever stoic, appeared disheartened. Early on March 28, he and Kermit, accompanied by Lyra and Luiz Correia, a paddler, set out on foot from their camp to reconnoiter a daunting canyon that lay ahead. When they returned, filthy, drenched in rain and sweat, bruised and drained of energy, the dazed and somber look on Rondon’s face told the others that he had bad news.

The canyon continued for almost two miles, and its flow of water was broken by a half-dozen cataracts, one of which was more than 30 feet high. Rondon saw no way to navigate through that gantlet in the canoes, but he also deemed it impossible to detour around the gorge with another portage. Worse, the canyon marked the start of rocky, hilly terrain that extended for miles.

So Rondon proposed a desperate solution: abandon the canoes, reduce equipment yet again, hike to the end of the mountains and build new canoes there. “To all of us his report was practically a sentence of death,” Cherrie wrote.

Kermit openly disagreed with Rondon. He had acquired formidable rope-handling skills while working as an engineer, and he and Lyra thought they could get some of the canoes through the canyon. Roosevelt supported his son, as did Cajazeira and the camaradas, who worked closely with Kermit and liked him. Rondon, overruled, gave in, but for the first time the others could read doubt on his face.

It took nearly four days to get the canoes through the canyon. “Hard work; wet all day; half ration” was Kermit’s laconic summary in his diary on the second day. But they succeeded with only the smallest canoe sacrificed, and with no loss of life.

Almost immediately, though, the group was thrust into a new crisis. After they made camp, at dusk, on April 2, Manoel Vicente da Paixão, a towering Black army corporal Rondon had placed in charge of the camaradas, caught a paddler named Julio de Lima stealing food from the ration tins. The brawny Paixão punched the thief in the face and warned him against raiding the provisions again. The next morning, while the men hauled crates down to the canoes, another paddler caught de Lima secretly gobbling the last of a tin of beef jerky. Then Paixão noticed him straggling behind the others, carrying a much lighter load, and dressed him down again. Arriving at the staging point, Paixão laid down the carbine he carried before heading back to fetch another load. De Lima was not far behind him.

Suddenly the crack of a firearm echoed above the rapids. Roosevelt, rifle in hand, and Cajazeira, armed with a revolver, rushed up the trail. They found Paixão lying facedown in his own blood. The doctor, kneeling to examine him, noted the gunpowder residue indicating that de Lima had fired point-blank, shooting Paixão through the heart.

Now everyone was in danger. De Lima was still armed and hiding nearby. Rondon was “in a blind rage to kill” him, Kermit wrote. But the commander soon recovered his equilibrium and ordered his most capable scouts to try to pick up de Lima’s trail and apprehend him. Roosevelt had already sent Kermit and Cherrie to guard the canoes, so Rondon ordered a pair of camaradas, duly armed, to watch over the provisions. Others got to work digging a grave for the esteemed Paixão.

The scouts returned, holding de Lima’s carbine aloft, which they had recovered from a tangle of vines, where he appeared to have abandoned it. This greatly reduced the risk that de Lima might attempt to kill someone else, and it left the murderer defenseless. Turning to Roosevelt, Rondon remarked: “Now he will be punished by the force of the circumstances in which he has placed himself.”

The explorers, down to 19 weary and dejected men, hastily buried Paixão, then resignedly returned to their portage.

Roosevelt was feverish again and so short of breath that he could take only a few steps before pausing. “Mr. Roosevelt arrived after great effort, worn out by the pathway, which rose sharply along the rocky mountainside,” Rondon wrote. “Such brutal exercise was excessive for his state of health, and made him suffer horribly.”

Roosevelt was aware he could no longer keep up. “The expedition cannot delay,” he told Rondon. “On the other hand, I can’t go on. Move on and leave me!”

Rondon wouldn’t hear it. “Allow me to observe,” he said, “that this expedition bears the names of Roosevelt and Rondon. It is therefore not possible for us to separate.”

That night, as Kermit and Cajazeira took turns caring for him, Roosevelt slipped into a delirium and repeatedly recited the opening lines of Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan”: “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / a stately pleasure-dome decree.” Then he descended into gibberish, with occasional bursts of lucidity reflecting concern for his companions: “I can’t work now, so I don’t need much food,” Kermit would recall his father saying, oblivious to his son’s presence. “But he and Cherrie have worked all day with the canoes, they must have part of mine.”

Roosevelt’s fever broke just before dawn. On the morning of April 5, Palm Sunday, it appeared the expedition was finally nearing the end of the long, narrow canyon. Kermit, now feverish himself, accompanied Rondon and Lyra on a hike downstream and concluded, as he wrote in his diary, “that after these rapids we’re out of the hills.” They returned to camp just in time to hear Paresi excitedly announce that he’d spotted spider monkeys in the canopy nearby. Kermit and Cherrie grabbed their guns and shot three of the animals; Kermit captured a turtle, which went into the pot. “The fresh meat we all craved gave us renewed strength and energy,” Cherrie wrote, “and the fact that the mountains that had for so long hemmed us in seemed at last to be falling away from the river brought us new courage.”

On Easter Sunday, the explorers spent eight hours hauling their equipment while the canoes ran the rapids. “Father not well,” Kermit wrote that night. “Much worried.”

The next day, Roosevelt was so debilitated that he had to travel flat on his back, shielded only by a piece of canvas and what remained of a broad-brimmed straw hat that insects had mostly consumed. He “won’t be with us tonight,” Cherrie would later recall thinking.

On April 15, Rondon, now in the lead canoe, spotted a crude sign nailed to a tree along the riverbank and carved with the initials “J.A.” Before long, the explorers found a thatched hut in the middle of a planted clearing, guarded by three yelping dogs. Inside were sacks of cassava flour and rice as well as an ample supply of yams. But the owner, a rubber tapper, was not there, and Rondon refused to allow his famished men to help themselves to the provisions. Instead, he left a note listing the names of all the surviving members of the expedition and where they had come from.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/c0/0dc03006-c0b9-479c-bb90-695962160cb5/aprmay2023_d03_amazon.jpg)

Several miles downstream, the explorers encountered another person, an old man who, assuming they were an Indian war party, frantically began to paddle away. It was only when Rondon stood up, waved his helmet, and called out to him in Portuguese that the rubber tapper allowed the four dugouts, filled with emaciated, feverish, bearded men in rags, to come alongside. The man had no food to share, but he told Rondon that they could obtain provisions from other rubber tappers nearby. A few miles downstream, the explorers saw puffs of smoke coming from a hut, and a woman with a baby in her arms rushed outside, took one look at them, screamed and ran off into the jungle.

Rondon ordered the paddlers to stop and make camp while waiting for the woman to return, presumably with her husband. Kermit and Cherrie carried Roosevelt to the hut and laid him on a cot. The cook already had a fire going when the couple appeared with two neighbors armed with rifles. But once they realized that their guests, though haggard, were part of a government party, they were generous and helpful with food and information.

That night, a camarada named Antônio Correia remarked to Kermit, “It seems like a dream to be in a house again, and hear the voices of men and women, instead of being among those mountains and rapids.”

The next morning, Cajazeira operated on Roosevelt’s leg—and without anesthetic, for Roosevelt had not mentioned that he kept a vial of morphine hidden in his belongings, in case he needed to take his own life. While the canoes were being packed, Cajazeira sliced into the swollen tissue and watched it empty of pus. He then inserted a drainage tube into the incision. Roosevelt lay silent. When Cajazeira finished, Kermit and Cherrie helped the weakened patient into the dugout.

The following day, while Rondon and Lyra took advantage of a cloudless sky to plot the expedition’s coordinates, Kermit visited local rubber tappers and came back with five pounds of rice. Six hours downstream, they encountered a man Kermit called “a certain Barbosa” in a riverside manor house. The man not only “gave us a duck and a chicken and some cassava and six pounds of rice, and would take no payment,” Roosevelt recorded, but he furnished them with new clothes. He also accepted a small canoe in exchange for use of a large, flat-bottomed boat, big enough to erect a tent to protect Roosevelt from the elements.

But the infection spread throughout Roosevelt’s body, and he developed an abscess on his right buttock so severe that he could not sit down. “He eats very little,” Cherrie wrote. “He is so thin that his clothes hang like bags on him.”

The expedition was moving quickly now, and after a set of rapids the explorers found a general store, the first they had seen in more than three months. The next day, April 23, the explorers began to encounter heavily laden batelões making their way upstream, carrying food and other supplies to remote settlements. The boat pilots all recognized Rondon. One after another, they passed on the good news: A welcome party was waiting for them at the junction of the Castanho and the Aripuanã Rivers, only four days away.

The weary and bedraggled men reached the confluence of these two majestic rivers on Sunday, April 26. Behind them lay almost unimaginable trials and privations that resulted in the deaths of three of their group, prostrated many with illness and forced each to endure long periods of hunger. Ahead loomed worldwide acclaim for the feat they had accomplished: mapping the previously unknown tropical River of Doubt over the course of its nearly 1,000 miles.

The next morning, Rondon formally renamed the River of Doubt. It would be the Roosevelt River. The men drove a wooden obelisk into the spongy ground and gathered around it for a series of photographs. Hat in hand, eyeglasses fogged in the intense humidity, Roosevelt was visibly haggard and gaunt: His clothes hung loosely from his body, and he held on to the obelisk to steady himself. Rondon, several inches shorter than Roosevelt and dozens of pounds lighter, posed almost nonchalantly in his simple olive military garb, his hands thrust into his jacket pockets and an impassive expression on his lean, copper-colored face.

Less than a week later, Roosevelt lay recuperating in a bed at the governor’s palace in Manaus. Cajazeira had spirited the former president from his quarters aboard the government steamship that had picked them up at the camp of a rubber baron and operated immediately, lancing Roosevelt’s abscess and draining it. He also gave the former president heart medication and prescribed a strict regimen of quinine.

Roosevelt sent a telegram to his wife announcing that he and Kermit had survived, and another message to the Brazilian foreign minister in Rio de Janeiro. “We have had a hard and somewhat dangerous but very successful trip,” he wrote, before enumerating the expedition’s perils and major achievements. “My dear Sir, I thank you from my heart for the chance to take part in this great work of exploration.”

On May 7, Rondon and Roosevelt said goodbye in Belém, at the mouth of the Amazon. Meeting with reporters, his ill health evident, Roosevelt emphasized the expedition’s accomplishments: “We have put on the map a river nearly one thousand miles long,” he said. “It is the biggest tributary of the biggest tributary of the most magnificent river in the world.”

Then Rondon and the other Brazilians came on board the steamship Aidan to say goodbye. Roosevelt shook hands with every camarada, gave each two gold sovereigns and made a speech, which Kermit translated into Portuguese. “You are all heroes,” he told them, adding that they were “a fine set—brave, patient, obedient and enduring.” Nor was Simplício forgotten: Roosevelt directed that his gold coins be sent to his mother.

Roosevelt was even more effusive about the officers, and whatever disagreements had divided him and Rondon during their trip now gave way to what Rondon described as a mutual affection “spontaneously born of the dangerous but beautiful deed that together we had just accomplished.”

Roosevelt concluded by inviting Rondon to visit him at his home in Sagamore Hill, New York. Smiling, Rondon replied, “I’ll be there when you are again elected president of the United States, to attend your swearing-in.” But though they would occasionally write, Rondon and Roosevelt never saw each other again. In fact, Roosevelt never made another try at the presidency, and though there was talk of his possibly running in 1920, he didn’t live that long, dying at Sagamore Hill on January 6, 1919, at the age of 60.

Of the principal expedition members, Rondon would live the longest, and he participated in a dozen more missions. He died in 1958, at the age of 92. Although he remains little known outside Brazil, in his homeland he is a hero whose face has appeared on currency and whose name graces streets, squares, museums, airports, government buildings, cities, counties and even a state: Rondônia.

Adapted from Into the Amazon, by Larry Rohter. Copyright © 2023. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1863x1384:1864x1385)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/86/31863e39-9831-44aa-88cb-a69196c73fa9/aprmay2023_d01_amazon.jpg)