Teen Idol Frankie Lymon’s Tragic Rise and Fall Tells the Truth About 1950s America

The mirage of the singer’s soaring success echoes the mirage of post-war tranquility at home

:focal(1314x1228:1315x1229)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/cc/83cc21e7-e6d3-49ef-949f-734c53f405b4/janfeb2018_h01_frankielymon.jpg)

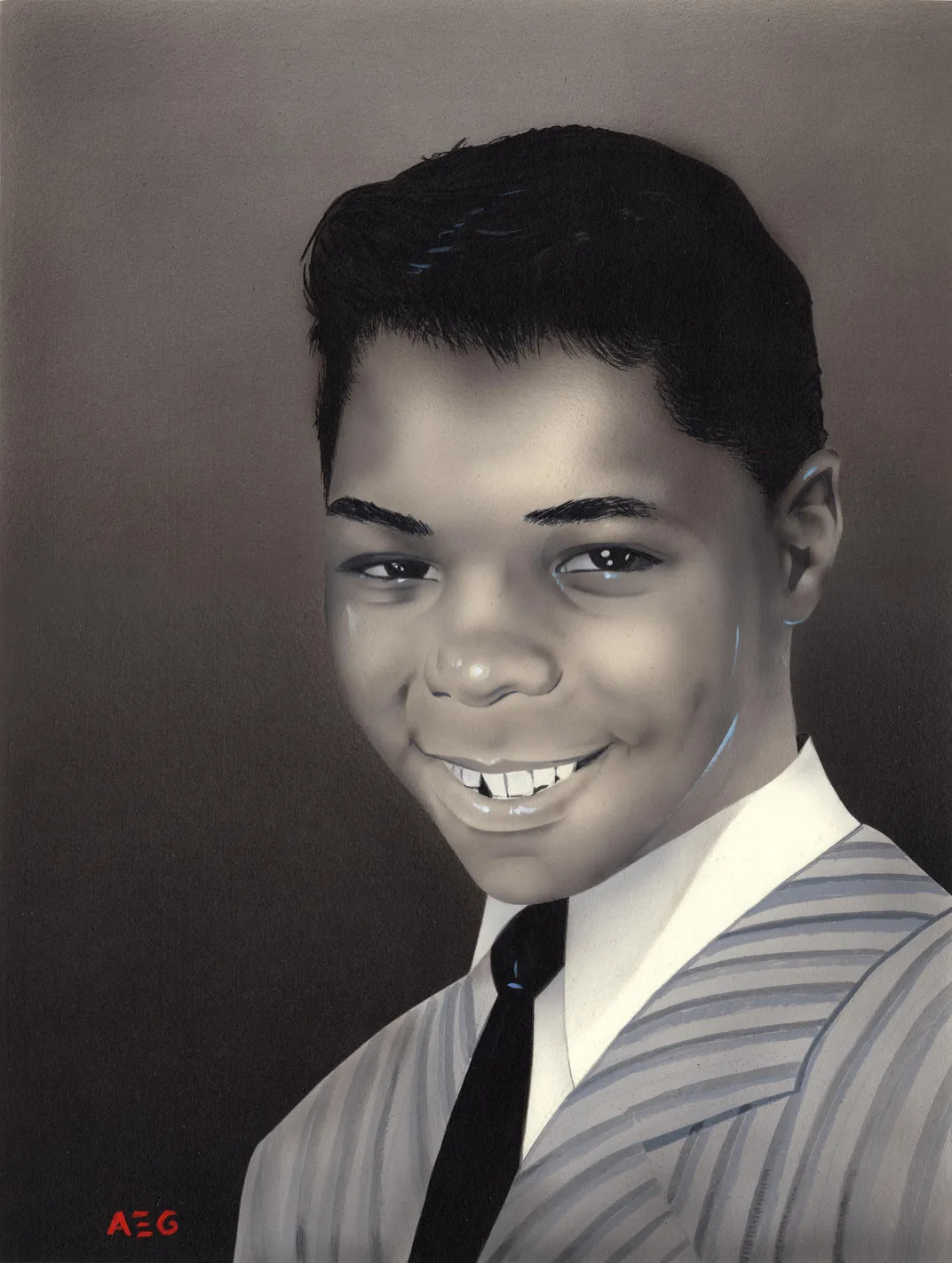

That voice! Those apple cheeks! Arms wide, head back, he radiates joy, even in antique black and white. That beautiful soprano flying high, talent and presence and just enough ham to sell it all. And it was a great story, too: Up from nothing! A shooting star! So when they found Frankie Lymon dead at the age of 25 one February morning in 1968, in the same apartment building where he’d grown up, it was the end of something and the beginning of something, but no one was quite sure what.

Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers were five kids from Washington Heights, just north of Harlem. They sang doo-wop under the streetlight on the corner of 165th and Amsterdam. They were discovered by the Valentines’ lead singer Richie Barrett while the kids were rehearsing in an apartment house. A few months later their first record, “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” made it to the top of the national charts. It was 1956. Overnight, Frankie Lymon was the hottest singer in America, off on a world tour. He was 13 years old.

That made him the first black teenage pop star, a gap-toothed, baby-faced, angel-voiced paragon of show business ambition, and a camera-ready avatar of America’s new postwar youth movement. He was a founding father of rock ’n’ roll even before his voice had changed. That voice and that style influenced two generations of rock, soul and R&B giants. You heard his echoes everywhere. The high, clear countertenor, like something out of Renaissance church music, found its way from the Temptations to the Beach Boys to Earth, Wind & Fire. Even Diana Ross charted a cover of “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” 25 years after its release. Berry Gordy may not have modeled the Jackson 5 on Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, as is often said, but it sure sounded as if he had.

That’s the legend, anyway. Truth is, Frankie Lymon grew up too fast in every way imaginable. “I never was a child, although I was billed in every theater and auditorium where I appeared as a child star,” Lymon told Art Peters, a reporter for Ebony magazine, in 1967. “I was a man when I was 11 years old, doing everything that most men do. In the neighborhood where I lived, there was no time to be a child. There were five children in my family and my folks had to scuffle to make ends meet. My father was a truck driver and my mother worked as a domestic in white folks’ homes. While kids my age were playing stickball and marbles, I was working in the corner grocery store carrying orders to help pay the rent.”

A few days before Frankie and his friends from the corner recorded the song that made them famous, Rosa Parks was pulled off a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Less than two years later, Frankie danced with a white girl on a national television show, and the show was swiftly canceled. Another part of the legend.

Race integration in pop music was never going to be simple.

**********

America in the 1950s: postwar economy roaring, a chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage of the split-level house in Levittown, every cliché of union-made American middle-class prosperity held to be self-evident.

And music was a big part of that. Raucous and brawny, electrified, it felt like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis all fell from the sky at once. Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, with their tight, upbeat harmony, were an important part of it, too. You can trace doo-wop back to the Psalms, hear it bubble up in the a cappella harmonies of Gregorian chant, or, by way of Africa and the Caribbean, from gospel quartets.

In America, beginning in the 1930s, the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots were the popularizers of those intricate harmonies we recognize today as proto-rock ’n’ roll. Doo-wop was among the inheritors, a thousand street-corner groups and a thousand one-hit wonders. The Spaniels and the Five Satins and the Vocaleers, the Drifters and the Fleetwoods and the Moonglows, the Coasters and the Platters and on to Frankie Valli and modernity. In the 1950s, every high school stairwell in this country was loud with four-part singing. Even today the “Pitch Perfect” movie franchise owes its popularity to an a cappella tradition stretching back into pre-electric history.

“We harmonized every night on the street corner until the neighbors would call the cops to run us away,” Lymon told Ebony. But Frankie wasn’t doo-wop, not really. Doo-wop was group music. “Frankie Lymon was always different than that,” Robert Christgau, great-granddaddy of American rock critics and historians, will tell you. “He was the star.”

Frankie and his record producers and managers soon agreed he’d be a more profitable solo act, so off he went, leaving behind the Teenagers, and with them friendship and loyalty. He had another, lesser, hit—a recording of “Goody Goody,” sung by Bob Crosby and Ella Fitzgerald before him—before things cooled.

Then came the long, slow slide.

Ask any junkie and they’ll tell what they’re chasing is the feeling they got the first time they got high. But that first-time rush can never be recaptured, whether you’re talking about heroin or cigarettes or hit records.

Frankie was a heroin addict at 15 years old. He tried to kick, tried again and again and got straight for a while. Then his mother died, and he fell hard.

He wasn’t alone. Heroin was everywhere in New York by then, and methadone clinics run by the city were springing up in neighborhoods all over town. The failure rate was heartbreaking.

“I looked twice my age,” Lymon told Ebony. “I was thin as a shadow and I didn’t give a damn. My only concern was in getting relief. You know, an addict is the most pathetic creature on earth. He knows that every time he sticks a needle in his arm, he’s gambling with death and, yet, he’s got to have it. It’s like playing Russian Roulette with a spike. There’s always the danger that some peddler will sell him a poisoned batch—some garbage.” Here young Frankie knocks on wood. “I was lucky. God must have been watching over me.”

Even now you want to believe him.

**********

Frankie’s neighborhood, just up the bluffs from the long-gone Polo Grounds, feels mostly unchanged even 50 years later. It was poorer then, sure, like the rest of New York City, and in the age before earbuds and headphones it was surely louder. You heard music in the streets.

Outside Frankie’s old address, on West 165th, there’s a “Wet Paint” sign on the door this bright autumn morning, and one building over a crew is painting the ancient fire escapes. The whole block smells of solvent, sharp and clean. It’s a well-kept street of five- and six-story apartment houses in a tidy neighborhood of working-class folks who greet each other on the sidewalk, black and white and brown, Latin American and Caribbean immigrants and Great Migration African-Americans and, like the rest of New York, folks from all over.

Young as he was, Lymon had three wives. He married them in quick succession, and there was plenty of confusion about the paperwork. He may have been married to more than one at a time, or not entirely married to one of the three at all. One of them may have still been married to someone else. Depends whom you ask. (In the 1980s, they all met in court, to settle Lymon’s estate, such as it was, to find out who was entitled to songwriting royalties from best sellers like “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” None got much, but the third wife, Emira Eagle, received an undisclosed settlement from record producers.)

In 1966, there was a brief glimmer of hope. Fresh out of rehab at Manhattan General Hospital, Lymon appeared at a block party organized by a group of nuns at a Catholic settlement house in the Bronx. He told an audience of 2,000 teenagers, “I have been born again. I’m not ashamed to let the public know I took the cure. Maybe my story will keep some other kid from going wrong.”

On February 27, 1968, he was booked for a recording session to mark the start of a comeback. Instead, he was found dead that morning on his grandmother’s bathroom floor.

**********

Frankie Lymon was buried in the Bronx, at St. Raymond’s Cemetery: Row 13, Grave 70. It’s 15 minutes by car from the old neighborhood. His headstone is over by the highway. The grass is green and the ground is hard and uneven and on the left his stone is packed tight with the others. On the right there’s a gap like a missing tooth. You can see the towers of two bridges from here, the Bronx-Whitestone and Throgs Neck, and hear the traffic rush past on the Cross Bronx Expressway. Billie Holiday is buried here, and Typhoid Mary. This is where the Lindbergh ransom exchange happened. The wind comes hard off Eastchester Bay and shakes the pagoda trees.

For years Frankie’s grave was unmarked. In the mid-1980s, a New Jersey music store held a benefit to raise money for a memorial, but it never made it to the cemetery. The headstone gathered dust in the record shop, then moved at last to the backyard of a friend of the owner.

Emira Eagle had the current headstone installed sometime in the late 1990s.In Loving Memory

Of My HusbandFrank J. LymonSept. 30, 1942 – Feb. 27, 1968

Not much room to tell his story. And what could anyone say? That the 1950s were long over? That innocence was dead? That by 1968 one America had vanished entirely, and another had taken its place?

Or maybe that Frankie Lymon’s America, doo-wop America, was never simple, never sweet, but was rather an America as complex and wracked by animus and desire as any in history. It was the same America that killed Emmett Till, after all, another angel-faced kid with apple cheeks and a wide, bright smile.

Seen across the gulf of years, what we now think of as the anodyne, antiseptic 1950s America is revealed as an illusion. June Cleaver vacuuming in an organdy cocktail dress and pearls is a television mirage, a national hallucination. We had the postwar world economy to ourselves because so many other industrial nations had been bombed flat. And for every Pat Boone there was a “Howl,” an Allen Ginsberg, a Kerouac, a Coltrane, a Krassner, a Ferlinghetti. There were underground explosions in painting and poetry and music and prose. It was a kind of invisible revolution.

A telling detail of that chaste 1950s mythology: to preserve his image as a clean-cut teenager, Frankie Lymon would pass off the women he dated in different cities as his mother. It gets told and told and told—in fact, he told it himself—that he once got caught by a reporter who went to shows in New York and Chicago and saw that his “mom” was two different women, each twice Frankie’s age. A story too good to fact-check.

It was in these 1950s that Ralph Ellison wrote Invisible Man, and James Baldwin published Notes of a Native Son. After Rosa Parks was pulled off that bus, Dr. King led the Montgomery bus boycott and changed the trajectory of civil rights in America. The Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education, and then came Little Rock and the lunch counter sit-ins at Wichita and Oklahoma City. What you saw of the ’50s in America was all about where you stood. And with whom.

Was the short, blinding arc of Frankie Lymon’s career a morality play? A rock ’n’ roll cautionary tale? Or just another story of a young man gone too soon?

Maybe it was a reminder that America changes in every instant and never changes at all. Our streets have always been filled with music and temptation; addiction has always been with us, long before “us” was even America, from the Lotus Eaters of The Odyssey to the opium dens of the Wild West to the crack epidemic and on to our own new opioid crisis.

Looking at that headstone, you get to thinking maybe Frankie Lymon was the 1950s, man and myth, the junkie with an angel’s voice, and that the stone stands as a monument to the lies we tell ourselves about America in the time before Frankie flew away.

The very night Lymon died Walter Cronkite went on the air and said of Vietnam, “We are mired in a stalemate.” It was clear the center couldn’t hold, and if you felt like the 1950s were five polite young men in matching letter sweaters, the rest of 1968 came at you like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The world lurched and suddenly spun too fast. Tet. My Lai. Chicago. Washington. Baltimore. Riots everywhere. Vietnam the pulse and drumbeat behind and beneath everything.

So when Frankie Lymon died that February morning you’d have been forgiven for missing it. He was nearly forgotten by then, a five-paragraph item on page 50 of the New York Times, a casualty of the moment the future and the past came apart.

It was sad, but for a while, arms wide and head back, Frankie Lymon had bridged and bound all those opposing energies. That face! That voice!

Man, he could sing like an angel.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)