The Ten Best History Books of 2020

Our favorite titles of the year resurrect forgotten histories and help explain how the country got to where it is today

:focal(792x502:793x503)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/b7/b4b7f646-0474-471c-93e6-4b82e6707561/history_2.jpg)

In a year marked by a devastating pandemic, a vitriolic presidential race and an ongoing reckoning with systemic racism in the United States, these ten titles served a dual purpose. Some offered a respite from reality, transporting readers to such varied locales as Tudor England, colonial America and ancient Jerusalem; others reflected on the fraught nature of the current moment, detailing how the nation’s past informs its present and future. From an irreverent biography of George Washington to a sweeping overview of 20th-century American immigration, these were some of our favorite history books of 2020.

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents

In this “Oprah’s Book Club” pick, Isabel Wilkerson presents a compelling argument for shifting the language used to describe how black Americans are treated by their country. As the Pulitzer Prize–winning author tells NPR, “racism” is an insufficient term for the country’s ingrained inequality. A more accurate characterization is “caste system”—a phrase that better encapsulates the hierarchical nature of American society.

Drawing parallels between the United States, India and Nazi Germany, Wilkerson identifies the “eight pillars” that uphold caste systems: Among others, the list includes divine will, heredity, dehumanization, terror-derived enforcement and occupational hierarchies. Dividing people into categories ensures that those in the middle rung have an “inferior” group to compare themselves to, the author writes, and maintains a status quo with tangible ramifications for public health, culture and politics. “The hierarchy of caste is not about feelings or morality,” Wilkerson explains. “It is about power—which groups have it and which do not.”

The Great Secret: The Classified World War II Disaster that Launched the War on Cancer

When the Nazis bombed Bari, a Mediterranean port city central to the Allied war effort, on December 2, 1943, hundreds of sailors sustained horrific injuries. Within days of the attack, writes Jennet Conant in The Great Secret, the wounded started exhibiting unexpected symptoms, including blisters “as big as balloons and heavy with fluid,” in the words of British nurse Gwladys Rees, and intense eye pain. “We began to realize that most of our patients had been contaminated by something beyond all imagination,” Rees later recalled.

American medical officer Stewart Francis Alexander, who’d been called in to investigate the mysterious maladies, soon realized that the sailors had been exposed to mustard gas. Allied leaders were quick to place the blame on the Germans, but Alexander found concrete evidence sourcing the contamination to an Allied shipment of mustard gas struck during the bombing. Though the military covered up its role in the disaster for decades, the attack had at least one positive outcome: While treating patients, Alexander learned that mustard gas rapidly destroyed victims’ blood cells and lymph nodes—a phenomenon with wide-ranging ramifications for cancer treatment. The first chemotherapy based on nitrogen mustard was approved in 1949, and several drugs based on Alexander’s research remain in use today.

Read an excerpt from The Great Secret that ran in the September 2020 issue of Smithsonian magazine.

Uncrowned Queen: The Life of Margaret Beaufort, Mother of the Tudors

Though she never officially held the title of queen, Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, fulfilled the role in all but name, orchestrating the Tudor family’s rise to power and overseeing the machinations of government upon her son Henry VII’s ascension. In Uncrowned Queen, Nicola Tallis charts the complex web of operations behind Margaret’s unlikely victory, detailing her role in the Wars of the Roses—a dynastic clash between the Yorkist and Lancastrian branches of the royal Plantagenet family—and efforts to win Henry, then in exile as one of the last Lancastrian heirs, the throne. Ultimately, Margaret emerges as a more well-rounded figure, highly ambitious and determined but not, as she’s commonly characterized, to the point of being a power-hungry religious zealot.

You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington

Accounts of George Washington’s life tend to lionize the Founding Father, depicting him as a “marble Adonis … rather than as a flawed, but still impressive, human being,” according to Karin Wulf of Smithsonian magazine. You Never Forget Your First adopts a different approach: As historian Alexis Coe told Wulf earlier this year, “I don’t feel a need to protect Washington; he doesn’t need me to come to his defense, and I don’t think he needed his past biographers to, either, but they’re so worried about him. I’m not worried about him. He’s everywhere. He’s just fine.” Treating the first president’s masculinity as a “foregone conclusion,” Coe explores lesser-known aspects of Washington’s life, from his interest in animal husbandry to his role as a father figure. Her pithy, 304-page biography also interrogates Washington’s status as a slaveholder, pointing out that his much-publicized efforts to pave the way for emancipation were “mostly legacy building,” not the result of strongly held convictions.

Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man and the Gospel of Jesus's Wife

Nine years after Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code popularized the theory that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene, Harvard historian Karen L. King announced the discovery of a 1,600-year-old papyrus that seemingly supported the novel’s much-maligned premise. The 2012 find was an instant sensation, dividing scholars, the press and the public into camps of non-believers who dismissed it as a forgery and defenders who interpreted it as a refutation of longstanding ideals of Christian celibacy. For a time, the debate appeared to be at an impasse. Then, journalist Ariel Sabar—who’d previously reported on the fragment for Smithsonian—published a piece in the Atlantic that called the authenticity of King’s “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” into question. Shortly after, King publicly stated that the papyrus was probably a forgery.

Veritas presents the full story of Sabar’s seven-year investigation for the first time, drawing on more than 450 interviews, thousands of documents, and trips around the world to reveal the fascinating figures behind the forgery: an amateur Egyptologist–turned–pornographer and a scholar whose “ideological commitments” guided her practice of history. Ultimately, Sabar concludes, King viewed the papyrus “as a fiction that advanced a truth”: namely, that women and sexuality played a larger role in early Christianity than previously acknowledged.

The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President's Black Family

Bettye Kearse’s mother had long viewed her family’s ties to President James Madison as a point of pride. “Always remember—you’re a Madison,” she told her daughter. “You come from African slaves and a president.” (According to family tradition, as passed down by generations of griot oral historians, Madison raped his enslaved half-sister, Coreen, who gave birth to a son—Kearse’s great-great-great-grandfather—around 1792.) Kearse, however, was unable to separate her DNA from the “humiliation, uncertainty, and physical and emotional harm” experienced by her enslaved ancestor.

To come to terms with this violent past, the retired pediatrician spent 30 years investigating both her own family history and that of other enslaved and free African Americans whose voices have been silenced over the centuries. Though Kearse lacks conclusive DNA or documentary evidence proving her links to Madison, she hasn’t let this upend her sense of identity. “The problem is not DNA,” the author writes on her website. “... [T]he problem is the Constitution,” which “set the precedent for the exclusion of [enslaved individuals] from historical records.”

The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West

While Union forces fought to end slavery in the American South, a smaller cadre of soldiers waged war in the West, battling pro-secessionist troops for control of the resource-rich Arizona and New Mexico Territories. The campaign essentially ended in late 1862, when the U.S. Army pushed Confederate forces back into Texas, but as Megan Kate Nelson writes in The Three-Cornered War, another battle—this time, between the United States and the region’s Apache and Navajo communities—was just beginning. Told through the lens of nine key players, including Apache leader Mangas Coloradas, Texas legislator John R. Baylor and Navajo weaver Juanita, Nelson’s account underscores the brutal nature of westward expansion, from the U.S. Army’s scorched-earth strategy to its unsavory treatment of defeated soldiers. Per Publishers Weekly, Nelson deftly argues that the United States’ priorities were twofold, including “both the emancipation of [slavery] and the elimination of indigenous tribes.”

One Mighty and Irresistible Tide: The Epic Struggle Over American Immigration, 1924-1965

In 1924, Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, a eugenics-inspired measure that drastically limited immigration into the U.S. Controversial from its inception, the law favored immigrants from northern and Western Europe while essentially cutting off all immigration from Asia. Decisive legislation reversing the act only arrived in 1965, when President Lyndon B. Johnson (no relation), capitalizing on a brief moment of national unity sparked by predecessor John F. Kennedy’s assassination, signed the Hart-Celler Act—a measure that eliminated quotas and prioritized family unification—into law.

Jia Lynn Yang’s One Mighty and Irresistible Tide artfully examines the impact of decades of xenophobic policy, spotlighting the politicians who celebrated America’s status as a nation of immigrants and fought for a more open and inclusive immigration policy. As Yang, a deputy national editor at the New York Times, told Smithsonian’s Anna Diamond earlier this year, “The really interesting political turn in the '50s is to bring immigrants into this idea of American nationalism. It’s not that immigrants make America less special. It’s that immigrants are what make America special.”

The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X

When Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Les Payne died of a heart attack in 2018, his daughter, Tamara, stepped in to complete his unfinished biography of civil rights leader Malcolm X. Upon its release two years later, the 500-page tome garnered an array of accolades, including a spot on the 2020 National Book Awards shortlist. Based on 28 years of research, including hundreds of interviews with Malcolm’s friends, family acquaintances, allies and enemies, The Dead Are Arising reflects the elder Payne’s dedication to tirelessly teasing out the truth behind what he described as the much-mythologized figure’s journey “from street criminal to devoted moralist and revolutionary.” The result, writes Publishers Weekly in its review, is a “richly detailed account” that paints “an extraordinary and essential portrait of the man behind the icon.”

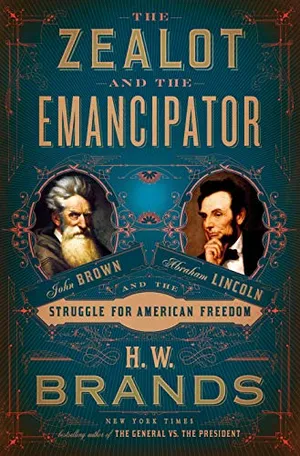

The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom

In this dual biography, H.W. Brands seeks to address an age-old question: “What does a good man do when his country commits a great evil?” Drawing on two prominent figures in Civil War history as case studies, the historian outlines differing approaches to the abolition of slavery, juxtaposing John Brown’s “violent extremism” with Abraham Lincoln’s “coolheaded incrementalism,” as Alexis Coe writes in the Washington Post’s review of The Zealot and the Emancipator. Ultimately, Brands tells NPR, lasting change requires both “the conscience of people like John Brown” (ideally with an understanding that one can take these convictions too far) and “the pragmatism and the steady hand of the politician—the pragmatists like Lincoln.”

Having trouble seeing our list of books? Turn off your ad blocker and you'll be all set. For more recommendations, check out The Best Books of 2020.

By buying a product through these links, Smithsonian magazine may earn a commission. 100 percent of our proceeds go to supporting the Smithsonian Institution.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)