Ten Curious Cases of Getting Lost in the Wilderness

Historical accounts of disorientation tell us a lot about how people have navigated relationships and space over time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/3d/f13dfc6b-d62c-4f0e-b178-4edc81996a3b/lost_in_the_wilderness-main.jpg)

People get lost all the time. Usually, these bouts of disorientation end happily enough. A hiker backtracks to find a missed trail marker, or a driver rolls down a window to ask a pedestrian for directions to a certain street or landmark. However, every so often, people get utterly lost, so lost that they scramble their brains along with their bearings. I call this extreme version of getting lost “nature shock,” the title of my new book, and eight years ago, I set out to find the terribly lost in American history.

Over five centuries, North Americans traveled from relational space, where people navigated by their relationships to one another, to individual space, where people understood their position on Earth by the coordinates provided by mass media, transportation grids and commercial networks. By meeting distressed individuals teetering on the edges of the worlds they knew, I learned how people constructed their worlds and how these constructions changed over time. And in so doing, I stumbled upon the twisted route Americans followed to reach a moment when blue dots pulsating on miniature screens tell them where to go.

The trader

In 1540, Perico, a Native American guide in the involuntary service of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s invading army, met his limit. The boy was a nimble navigator, a skilled linguist and monger of gossip. Prior to being taken captive, enslaved and baptized by the Spaniards, Perico had traversed the Mississippian chiefdoms of the southeast, suppling wealthy clients with goods like oyster-shell jewelry and copper disks. He connected people and commodities across territories by extracting news of high-demand ceremonial items from strangers. On the outskirts of a thick forest 20 miles from Cotifachequi, a city rumored to possess gold in the uplands of today’s South Carolina, Perico’s network failed him. He ran out of people to ask for directions and “began to foam at the mouth and throw himself to the ground as if possessed by the Devil.” While his captors watched on, he came undone, an excruciating ordeal brought on by social dislocation as much as geographic confusion. Perico recovered enough to lead de Soto into a weeks-long ramble in the woods, but he remained shaky until the army accidentally stumbled upon some local residents with whom he could converse.

The governor

Samuel de Champlain commanded the French empire in North America in the early 17th century, yet he could not be trusted to go for a walk in the woods by himself. One morning in 1615, Champlain chased a bird into a forest north of Lake Ontario. He was not supposed to be doing this. His Huron hosts had asked him to stay in camp while they went out deer hunting. But camp was boring, and the bird, according to Champlain, was “peculiar.” The size of a plump hen, it had the beak of a parrot and “was entirely yellow, except the head which was red, and the wings which were blue.” After following the creature as it flew from perch to perch, Champlain looked around and realized that he had no clue where he was. He wandered lost for the next three days, praying to God for a rescue until he happened upon a waterfall he recognized and followed the stream down to his hosts’ camp. The Hurons “begged” Champlain “not to stray off from them any more.” They did not want to be held responsible for his disappearance, or worse, death. In relational space, Native caretakers kept their eyes on colonial transplants to prevent catastrophic blunders.

The pilgrim

In the summer of 1621, a young man got completely turned around in the countryside beyond Plymouth Colony. “John Billington,” wrote Governor William Bradford, “lost himself in the woods and wandered up and down some five days, living on berries and whatever he could find.” Bradford’s vertical description of Billington’s horizontal predicament captured the panic of bewilderment. Up or down meant little in the jumble of paths, brooks, woods, cranberry bogs and meadows. Being robbed of a sense of direction, an awareness akin to the pull of gravity, felt like floating or falling.

After five days, a group of Native Americans ran into Billington and passed him east, along the length of Cape Cod, to the Nausets, who held him for ransom. Bradford called in a favor from his main indigenous ally, Massasoit, the Wampanoag sachem, to act as an emissary and deployed the colony’s limited supply of trade goods to retrieve the wayward youth. Colonists ranging alone in environments unfamiliar to them became targets of both hospitality and hostility. The severity of their lostness depended on the kindness or the cruelty of strangers who were at home in spaces the colonists’ viewed as wilderness.

Nature Shock: Getting Lost in America

An award‑winning environmental historian explores American history through wrenching, tragic, and sometimes humorous stories of getting lost.

The widow

In 1796, a New Hampshire woman left her four daughters at home while she went to bring in the cows just before dark. In the woods, she “became bewildered, and had no idea which way pointed home.” After wandering the forest paths for hours, she spied the “dim light” of Benjamin Badger’s house, a neighbor whose farm lay two miles from her own. By the time Badger grabbed a lantern to light the widow’s way home, it was near midnight. Though a brief skirmish with nature shock, the widow’s disorientation revealed how getting lost abetted identity theft. The widow operated an independent household. She ran a farm and raised four children by herself, yet in the story told of her misadventure only Benjamin Badger deserved individual mention. The woman remained “the widow” throughout, a nameless wanderer defined by a relationship. Being human, she became bewildered at dark in the woods; being a woman in the 18th century, her tracks as an independent householder were covered up by a male historian who perceived her not as the equal to Badger, which she was, but rather as a dead man’s helpmate.

The wunderkind

Paul Gasford got lost hunting for sarsaparilla on the shore of Lake Ontario in 1805. Eager to collect the sixpence reward his mother was offering the child who picked the most, he scurried through the brush, eyes peeled and legs pumping, giddy to be free of the small boat his family was using to move their belongings from the Bay of Quinté in Ontario to their new home in Niagara, New York. None of the bigger kids noticed that Paul was missing, a staggering oversight given that, according to The True and Wonderful Story of Paul Gasford, published in 1826, he was “a little over 4 years old.”

After a three-day search, Gasford’s parents gave him up for dead. Chances were slim that a child that young could survive multiple nights exposed in a strange place. But Paul Gasford was no ordinary kid. Instead of falling apart when he realized that he was lost, he remembered the adults saying that Niagara lay 40 miles away and decided to complete the final leg of the journey on his own. He found the lake and followed the coastline. He dug holes in the beach at night and snuggled deep into the sand to keep warm. He jammed a stick in the ground before he slept to stay oriented in the right direction in case he woke confused. He nibbled grapes when he grew hungry, but not too many, for he remembered his mother’s admonition not to gorge himself and sour his stomach. When he sauntered into town, the place exploded in celebration.

Gasford’s miraculous journey was turned into a children’s book. In an era that valorized independence, Gasford confirmed the revolutionary fantasy that little Americans, mature beyond their years, could navigate individual space on their own.

The freedom-seeker

An Oglala mule brought Jack into a summer camp bustling with Lakotas, fur traders and overland travelers in 1846. He swayed in the saddle, gripping the pommel as if it were the rail of a storm-tossed ship. Oglala Lakota women and children “came pouring out of the lodges” and encircled the animal and its rider. Their “screams and cries” drew more onlookers. Even at rest, Jack rocked and rolled, and his “vacant stare” sent shivers through the crowd. Three Oglala hunters had rescued him after discovering him lying face-down, alone on the plains. He had gone missing 33 days earlier, in early June, while out chasing wayward oxen and horses for his employer, John Baptiste Richard, the “bourgeois,” or proprietor, of Fort Bernard, a trading post on the North Platte River in what is now Wyoming.

Before Jack ran into trouble on the grasslands surrounding the North Platte, he ran away from slavery on a border-state Missouri farm. An escapee, Jack’s employment options were limited, and the multi-cultural workforce of the western fur trade offered a haven. A man hunting livestock for his employer, Jack got lost while pursuing the freedom to build a life outside slavery. His predicament revealed the grim reality of relational space—where human bonds included slavery—as well as the difficulties of navigating in individual space. Disconnection could bring thrilling liberation and disastrous isolation.

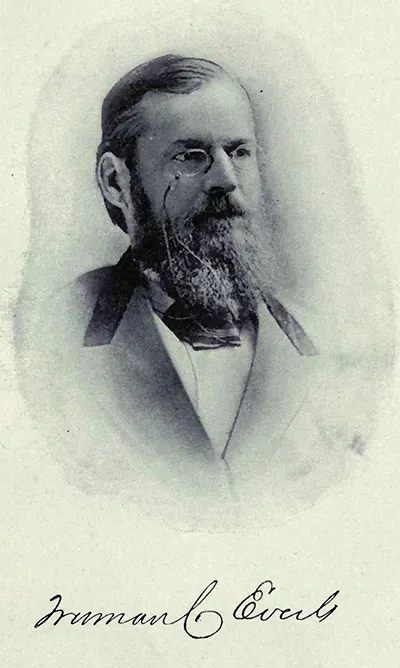

The explorer

Truman Everts went missing on the Yellowstone Plateau on September 9, 1870. A member of an exploration party sent by the federal government to catalog the region’s natural wonders, Everts, at first, took getting lost in stride. A romantic, he was enthralled by Yellowstone’s magnificent scenery. As hours turned to days and days to weeks, however, his outlook darkened. Two hunters found him on October 16. From a distance, they thought he was a bear, but the closer they got, the more confused they became. “When I got near it,” recalled one in the Helena Daily Herald on October 26, 1870, “I found it was not a bear, and for my life I could not tell what it was.” Everts was a sight to behold: “His flesh was all gone; the bones protruded through the skin on the balls of his feet and thighs. His fingers looked like bird claws.” He seemed “temporarily insane.” Later, Everts described holding conversations with imaginary friends in his worst moments of his bewilderment. He eventually recovered in body and mind. Everts abandoned his political career in the West, where he served as the Montana Territory’s tax assessor, and settled in Hyattsville, Maryland. He wiled away his final years working for the U.S. Postal Service.

The snob

In 1928, Jimmy Hale got lost searching for prehistoric relics in the caverns of the Ozark mountains in Arkansas. Hale fancied himself an expert archeologist because he had “read some books,” according to a 1928 article in Forest and Stream magazine. He lectured his host and guide, an experienced artifact hunter named Vance Randolph, on woodcraft, critiquing his fire-building skills and correcting his identification of woodpecker species. Two weeks into their trip, Hale left camp to hike “about three miles” through the woods to reach a nearby village and call his girlfriend. Relishing a morning free of Hale’s “putrid hokum,” Randolph urged him on his way, calling out as he entered the trees: “‘Well, don’t get lost!’” Hale failed to come back that night. Thinking the lad had decided to bed down in the village, Randolph held off searching for him until noon the next day, when he enlisted the help of a lumberjack named Lem. The searchers found where Hale had slept, a small cavern under a bluff, and in the next hollow, they spotted their man. He was marching along “shaking his head and tossing his arms wildly about.” Randolph called to him. Hale turned, glared at his guide without comprehension, and charged him, “frothing and spitting like a wounded wildcat.” .” Randolph ducked behind a bush, and the two “played hide-and-seek around a hazel thicket” until Hale spun off alone into the woods. Lem and Randolph discovered him face down in a snowbank a hundred yards away. After pouring corn whiskey down his throat to deaden his nerves, they carried him back to Lem’s cabin. The next morning, he remembered only a few details, like crossing his own trail and becoming frightened and running blindly through the forest. Randolph and Lem packed his bags and sent the humbled expert home to Massachusetts.

The pre-teen

On July 17, 1939, a 12-year-old Boy Scout named Donn Fendler summited Baxter Peak on Maine’s Mount Katahdin with his friend, Henry Condon. The boys had scrambled to the top ahead of their main hiking party, which included their fathers and Donn’s two brothers, Tom and Ryan. Clouds rolled in, and droplets of mist collected on Fendler’s sweatshirt and thin summer jacket. His teeth chattered, and he grew scared. He decided to backtrack to find his father. The child of an outdoor guide, Condon refused to go along. He hunkered down and waited. Fendler missed the trail and became lost. Nine days later, he stumbled out of the woods, 16 pounds lighter, missing his coat, his pants, his sneakers and the tip of one of his big toes, but clinging to a story of excruciating loneliness that would resonate with millions of people.

Fendler’s ordeal played out in a split screen of one lone wanderer and a mass media following. While he stumbled through days and shivered through nights alone, collecting insect bites, bruises and hallucinations, the press broadcast the search for him. “Thousands of mothers in America,” reported the Boston Evening Transcript, held their breath while reading “the papers daily for word.”

The hiker

In 1989, Eloise Lindsay went backpacking in Table Rock State Park in South Carolina to “think about what to do next with her life,” according to the Associated Press. Twenty-two years old, Lindsay had graduated college six months before she entered the woods and got lost. She missed the main trail and became disoriented. Panicking, she plunged into the brush “when she sensed that she was being followed.” Lindsay saw rescue helicopters circling for her, but she didn’t want to build a fire or come out into the open to signal the pilots for fear that her stalkers would find her first. She fled search parties, thinking they were the creeps out to get her. Rescued after two weeks hiding and wandering lost in the park, Lindsay insisted that two men had chased her and wanted to do her harm. The authorities could find no evidence of her pursuers.

Lindsay had wandered into a recreational nature preserve to find herself. She discovered nature shock instead, and her experience showed how pockets of bewilderment continue to ambush people even in an information age when transportation grids, government agencies and satellite networks guide most every move.

Jon T. Coleman is professor of history at the University of Notre Dame.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.