The True Story of Pocahontas Is More Complicated Than You Might Think

Historian Camilla Townsend separates fact from fiction in the life of the Powhatan “princess”

:focal(2808x1872:2809x1873)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/ad/bdad4ab3-7060-4946-b8a1-1091dfeefbf0/pocahontas1.jpg)

Pocahontas might be a household name, but the true story of her short, powerful life is buried in myths that have persisted since the 17th century.

First, Pocahontas wasn’t her actual name. Born around 1596 in present-day Virginia, she was really named Amonute, and she also had the more private name Matoaka. Pocahontas—which translates to “playful one” or “ill-behaved child”—was her childhood nickname.

Pocahontas was the favorite daughter of Powhatan, the formidable chief of more than 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes that lived in and around the area claimed by English settlers as Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Years later, when few firsthand witnesses were around to dispute his version of events, an English colonist named John Smith wrote about how Pocahontas, the beautiful daughter of a powerful Native leader, rescued him from execution at the hands of her father.

This narrative of Pocahontas turning her back on her own people and allying with the English, thereby finding common ground between the two cultures, has endured for centuries. But the truth of the matter was different from what Smith and mainstream culture say. And historians are divided over whether Pocahontas, then about 11 or 12 years old, rescued the mercantile soldier and explorer at all. Smith might have misinterpreted what was actually a ritual ceremony or even just lifted the tale from a popular Scottish ballad.

In 2017, 400 years after Pocahontas’ death in 1617, the Smithsonian Channel documentary Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth strove to tell its subject’s story accurately. In the film, authors, historians, curators and representatives of the Pamunkey tribe of Virginia, which descends from Pocahontas, paint a picture of a spunky, cartwheeling girl who grew up to be a clever and brave young woman, serving as a translator, ambassador and leader in her own right in the face of European colonization.

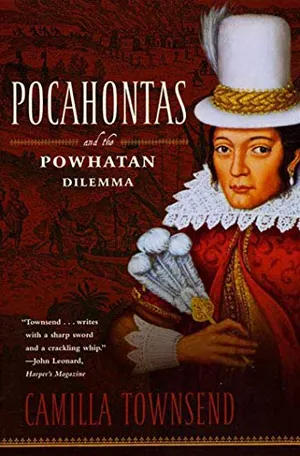

Camilla Townsend, author of the authoritative Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma and a historian at Rutgers University, is one of the experts featured in Beyond the Myth. To mark the documentary’s release in 2017, she talked to Smithsonian magazine about why Pocahontas’ story has been distorted for so long and why her true legacy is vital to understand today. Read a condensed and edited version of the conversation below.

Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma: The American Portraits Series

Camilla Townsend's "Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma" differs from all previous biographies of Pocahontas in capturing how similar 17th-century Native Americans were—in the way they saw, understood and struggled to control their world—not only to the invading British but to ourselves.

Discovering Pocahontas’ history

How did you become a scholar of Pocahontas?

I was a professor of Native American history for many years. I was working on a project comparing early relations between colonizers and Natives in Spanish America and English America when they arrived. I thought that I would be able to turn to other people’s work on Pocahontas, [her husband] John Rolfe and John Smith. There are truly hundreds of books over the many years that have been written about her. But when I tried to look into it, I found that most of them were full of hogwash. Many of them had been written by people who weren’t historians. Others were historians, [but] they were people who specialized in other matters and were taking it for granted that if something had been repeated several times in other people’s works, it must be true. When I went back and looked at the actual surviving documents from that period, I learned that much of what had been repeated about her wasn’t true at all.

During your extensive research, what were some details that helped you get to know Pocahontas better?

The documents that really jumped out at me were the notes that survived from John Smith. He was kidnapped by the Native Americans a few months after he got here [in spring 1607]. Eventually, after questioning him, they released him. But while he was a prisoner among the Native Americans, we know he spent some time with Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas and that they were teaching each other some basic aspects of their languages. And we know this because in his surviving notes are written sentences like “Tell Pocahontas to bring me three baskets,” or “Pocahontas has many white beads.” So, all of a sudden, I could just see this man and this little girl trying to teach each other, in one case English, in another case an Algonquian language. Literally in [late] 1607, sitting along some river somewhere, they said these actual sentences. She would repeat them in Algonquian, and he would write that down. That detail brought them both to life for me.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/17/f517496d-82d0-4090-9b1c-ca1dc12e583a/pocahontas_by_simon_van_de_passe_1616.jpeg)

The myths of Pocahontas

As you point out in the documentary, it’s not just Disney—with its 1995 animated film Pocahontas—that gets the story wrong. This goes back to Smith, who marketed their relationship as a love story. What class and cultural factors have allowed that myth to persist?

That story that Pocahontas was head over heels in love with John Smith has lasted for many generations. He mentioned it himself in the colonial period, as you say. Then it died, but it was born again after the American Revolution, in the early 1800s, when we were really looking for nationalist stories. Ever since then, it’s lived in one form or another, right up to the Disney movie and even today.

The reason it’s been so popular—not among Native Americans, but among people of the dominant [Western] culture—is that it’s very flattering to us. The idea is that this is a “good Indian.” She admires the white man, admires Christianity, admires the culture, wants to have peace with these people, is willing to live with these people rather than her own people, marry him rather than one of her own. That whole idea makes people in white American culture feel good about our history: that we were not doing anything wrong to the Indians but really were helping them, and the “good” ones appreciated it.

In real life, Pocahontas was a member of the Pamunkey tribe in Virginia. How do the Pamunkey and other Native people tell her story today?

It’s interesting. In general, until recently, Pocahontas had not been a popular figure among Native Americans. When I was working on the book, and I called the Virginia Council on Indians, for example, I got reactions of groans, because they were just so tired. Native Americans for so many years have been so tired of enthusiastic white people loving to love Pocahontas and patting themselves on the back because they love Pocahontas, when in fact what they were really loving was the story of an Indian who virtually worshipped white culture. They were tired of it, and they didn’t believe it. It seemed unrealistic to them.

I would say that there’s been a change recently. Partly, I think the Disney movie ironically helped. Even though it conveyed more myths, the Native American character is the star—she’s the main character, and she’s interesting, strong and beautiful, and so young Native Americans love to watch that movie. It’s a real change for them.

The other thing that’s different is that the scholarship is so much better now. We know so much more about her real life now that Native Americans are also coming to realize we should talk about her, learn more about her and read more about her, because, in fact, she wasn’t selling her soul, and she didn’t love white culture more than her own people’s culture. She was a spunky girl who did everything she could to help her people. Once they begin to realize that, they understandably become a lot more interested in her story.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/28/cf28d38e-85d0-474d-b8a4-542b6e11072d/poca_20161103_0021mxf03_30_25_01still001.jpg)

The lesson passed down by mainstream culture is that by leaving her people and adopting Christianity, Pocahontas became a model of how to bridge cultures. What do you think are the real lessons to be learned from Pocahontas’ life?

Largely, the lesson is one of extraordinary strength even against very daunting odds. Pocahontas’ people could not possibly have defeated or even held off the power of Renaissance Europe, which is what John Smith and the colonizers who came later represented. They had stronger technology, more powerful technology in terms of not only weapons but also shipping and book printing and compass making—all the things that made it possible for Europe to come to the New World and conquer, and the lack of which made it impossible for Native Americans to move toward the Old World and conquer. So, Native people were facing extraordinarily daunting circumstances. Yet in the face of that, Pocahontas and so many others that we now read about and study showed extreme courage and cleverness, sometimes even brilliance in the strategizing that they used. The most important lesson is that she was braver, stronger and more interesting than the fictional Pocahontas.

Telling the real story of the Native “princess”

Four hundred years after Pocahontas’ death, her story is being told more accurately. What has changed?

Studies of TV and other pop culture show that in that decade between the early 1980s and the early 1990s is when the real sea change occurred in terms of American expectations that we should really look at things from other people’s point of view, not just dominant culture’s. That had to happen first. So, let’s say by the mid- to late 1990s, that had happened. Then, more years had to go by. My Pocahontas book, for example, came out in 2004. Another historian wrote a serious segment about her that said much the same as I did, just with less detail, in 2001. So, the ideas of multiculturalism had gained dominance in our world in the mid-1990s, but another five to ten years had to go by before people had digested this and put it out in papers, articles and books.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/5b/3f5bcc37-5a10-4919-bfc3-20541d6e4c7e/img_8173.jpg)

Since the shift in mainstream scholarship is so recent, do you think there’s more to learn from Pocahontas’ story going forward?

There’s more to learn about her in the sense that it would help modern politics if more people understood what Native people really went through, both at the time of conquest and in the years after. There’s so strong a sense in our country, at least in some places among some people, that somehow Native Americans and other disempowered people had it good—they’re the lucky ones, with special scholarships and special status. That is very, very far from a reflection of their real historical experience. Once you know the actual history of what these tribes have been through, it’s sobering, and one has to reckon with the pain and the loss that some people have experienced far more than others over the last five generations or so. It would help everybody, both Native and mainstream culture, if more people understood what Native experience was really like both at the time of conquest and since.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sonja_headshot.png)