The Adventures of the Real Tom Sawyer

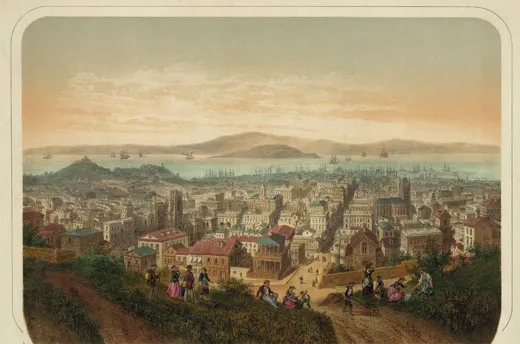

Mark Twain prowled the rough-and-tumble streets of 1860s San Francisco with a hard-drinking, larger-than-life fireman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Tom-Sawyer-town-1-631.jpg)

On a rainy afternoon in June 1863, Mark Twain was nursing a bad hangover inside Ed Stahle’s fashionable Montgomery Street steam rooms, halfway through a two-month visit to San Francisco that would ultimately stretch to three years. At the baths he played penny ante with Stahle, the proprietor, and Tom Sawyer, the recently appointed customs inspector, volunteer fireman, special policeman and bona fide local hero.

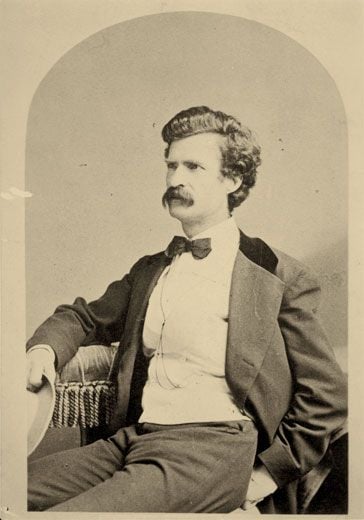

In contrast to the lanky Twain, Sawyer, three years older, was stocky and round-faced. Just returned from firefighting duties, he was covered in soot. Twain slumped as he played poker, studying his cards, hefting a bottle of dark beer and chain-smoking cigars, to which he had become addicted during his stint as a pilot for steamboats on the Mississippi River from 1859 until the Civil War disrupted river traffic in April 1861. It was his career on the Mississippi, of course, that led Samuel Clemens to his pen name, “mark twain” being the minimum river depth of two fathoms, or roughly 12 feet, that a steamboat needed under its keel.

Sawyer, 32, who was born in Brooklyn, had been a torch boy in New York for Columbia Hook and Ladder Company Number 14, and in San Francisco he had battled fire for Broderick 1, the city’s first volunteer fire company, under Chief David Broderick, the first fire chief. Twain perked up when Sawyer mentioned that he had also toiled as a steamboat engineer plying the Mexican sea trade. Twain well knew that an engineer typically stood between two rows of furnaces that “glare like the fires of hell” and “shovels coal for four hours at a stretch in an unvarying temperature of 148 degrees Fahrenheit!”

Sawyer had proved his heroism February 16, 1853, while serving as the fire engineer aboard the steamer Independence. Heading to San Francisco via San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua and Acapulco, with 359 passengers aboard, the ship struck a reef off Baja, shuddered like a leaf and caught against jagged rocks. “Don’t be afraid,” Captain F. L. Sampson told the passengers on deck. “You’ll all get to shore safely.” He pointed the ship head-on toward the sand, intending to beach it. In the raging surf the vessel swung around broadside.

THE FIERY SHIPWRECK—

SAWYER PLUNGES INTO THE SURF—

DARING RESCUE

*

Sawyer raced below deck and dropped into two feet of water. Through a huge rent, the sea was filling up overheated boilers below the waterline, cooling them rapidly. Chief Engineer Jason Collins and his men were fighting to keep steam up to reach shore. After the coal bunkers flooded, the men began tossing slats from stateroom berths into the furnaces. Sawyer heard Collins cry, “The blowers are useless!”

Loss of the blowers drove the flames out the furnace doors and ignited woodwork in the fire room and around the smokestack. Steam and flames blasted up from the hatch and ventilators. “The scene was perfectly horrible,” Sampson recalled later. “Men, women and children, screeching, crying and drowning.”

Collins and James L. Freeborn, the purser, jumped overboard, lost consciousness and sank. Sawyer, a powerful swimmer, dove into the water, caught both men by their hair and pulled them to the surface. As they clung to his back, he swam for the shore a hundred yards away, a feat of amazing strength and stamina. Depositing Collins and Freeborn on the beach, Sawyer swam back to the burning steamer. He made a number of round trips, swimming to shore with a passenger or two on his back each time.

Finally a lifeboat was lowered, and women, children and many men, including the ship’s surgeon, who would be needed on land, packed in and were rowed to shore. Two broken lifeboats were repaired and launched. Sawyer returned to the flaming vessel in a long boat, rowing hard despite burned forearms to reach more passengers. He got a group into life preservers, then towed them ashore and went back for more. An hour later, the ship was a perfect sheet of flame.

Four days later, the survivors were picked up by American whaling vessels. Ultimately, Sawyer was credited with saving 90 lives at sea, among them 26 people he had rescued singlehandedly.

Twain, floating in clouds of steam at Stahle’s baths, was riveted by Sawyer’s story. He himself had a deathly fear of exploding steamers, and for good reason. In 1858, Twain had gotten his brother Henry, then 20, an unpaid post as a junior purser on the New Orleans steamer Pennsylvania. On June 13, the Pennsylvania exploded 60 miles below Memphis. Four of the eight boilers blew up the forward third of the vessel. “Henry was asleep,” Twain later recalled, “blown up—then fell back on the hot boilers.” A reporter wrote that Twain, who had been nearly two days’ travel downriver from Memphis, was “almost crazed with grief” at the sight of Henry’s burned form on a mattress surrounded by 31 parboiled and mangled victims on pallets. “[Henry] lingered in fearful agony seven days and a half,” Twain later wrote. Henry died close to dawn on June 21. “Then the star of my hope went out and left me in the gloom of despair....O, God! This is hard to bear.”

Twain blamed himself and, at the time he and Sawyer met, was still reliving the tragedy in his memory by day and in vivid dreams by night.“My nightmares to this day,” he would write toward the end of his life, “take the form of my dead brother.”

MINING COUNTRY ESCAPADE—

THE MEN COMMENCE TO CAROUSE—

“I WAS BORN LAZY”

*

Only weeks after meeting Sawyer in San Francisco, Twain, in July 1863, went back to Virginia City, Nevada, where he’d previously worked as a correspondent for the Territorial Enterprise. He’d gotten free mining stocks as kickbacks for favorable mentions in the paper, and the value of his shares in the Gould and Curry mines had been soaring. “What a gambling carnival it was!” Twain later recalled. Now covering the rough-and-tumble silver-mining town as a freelancer for San Francisco’s Daily Morning Call, he sent for his new friend, Sawyer. “[Sam] wrote,” Sawyer recalled, “asking me to make him a visit. Well, I was pretty well-heeled—had eight hundred dollars in my inside pocket—and as there was nothing much doing in Frisco, I went.” Sawyer jolted 200 miles over mountain roads by stagecoach.

Sawyer had an exciting few nights with Sam and his friends, drinking and gambling. “In four days I found myself busted, without a cent,” Sawyer said later. “Where under the sun he got it has always been a mystery, but that morning Sam walked in with two hundred dollars in his pocket, gave me fifty, and put me on the stage for California, saying that he guessed his Virginia City friends was too speedy for me.”

After Sawyer left, Twain’s luck went bad. He moved into rooms in the new White House Hotel, and when it caught fire on July 26, most of his possessions and all his mining stocks were burned to ash. In Roughing It, he fictionalized the reason for his sudden poverty. “All of a sudden,” he lamented, “out went the bottom and everything and everybody went to ruin and destruction! The bubble scarcely left a microscopic moisture behind it. I was an early beggar and a thorough one. My hoarded stocks were not worth the paper they were printed on. I threw them all away.”

Twain returned to San Francisco in September 1863, a time of writing feverishly and much carousing. “Sam was a dandy, he was,” Sawyer said later. “He could drink more and talk more than any feller I ever seen. He’d set down and take a drink and then he’d begin to tell us some joke or another. And then when somebody’d buy him another drink, he’d keep her up all day. Once he got started he’d set there till morning telling yarns.”

Sawyer was nearly his equal in talking but often had to throw in the towel. “He beat the record for lyin’—nobody was in the race with him there,” Sawyer recalled. “He never had a cent. His clothes were always ragged and he never had his hair cut or a shave in them days. I should say he hasn’t had his hair cut since ’60. I used to give him half my wages and then he’d borrow from the other half, but a jollier companion and a better mate I would never want. He was a prince among men, you can bet, though I’ll allow he was the darndest homeliest man I ever set eyes on, Sam was.”

Stahle’s Turkish baths were housed in the Montgomery Block—at four stories the tallest building in the West when it was opened in 1853—at the intersection of Montgomery and Washington streets. The ground floor on the northwest corner housed the Bank Exchange saloon, where Twain and Sawyer had met. The Montgomery Block was perhaps the most important literary site of the 19th- and early 20th-century American West. Bret Harte, a frequent visitor to the bar, wrote “The Luck of Roaring Camp” in Montgomery Block quarters. Writers including Jack London, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the artist Ralph Stackpole, who would paint murals within Coit Tower, kept offices in the building. Sun Yat-sen wrote the first Chinese constitution there. Twain and fellow reporter Clement T. Rice were living in the Occidental, a prestigious new four-story hotel on Montgomery Street. Sawyer lived frugally while saving to buy a saloon on Mission Street.

Throughout 1863 and into 1864, Twain published unsigned stories in the Call. “They’d send him out down at the paper to write something up,” Sawyer remembered, “and he’d go up to the Blue Wing [saloon] and sit around telling stories and drinking all day.” He also frequented the bar at the Occidental. “Then he’d go back to the office and write up something. Most times it was all wrong, but it was mighty entertaining,” Sawyer allowed.

At the steam baths on July 8, 1864, Twain was miserable with a cold, sneezing and snuffling. Sawyer entered, smoked-black and fire-scorched, returning from the engine house of the Liberty Hose Number 2 company he had helped organize and for which he served as foreman. As they played cards, Twain admitted how much he loathed his job at the Call and detested its editor, George Barnes. He wanted to quit, but because of considerable debt, had vowed to drag himself into work and be pleasant to Barnes. “It was awful drudgery for a lazy man,” Twain explained, “and I was born lazy. I raked the town from end to end and if there were no fires to report, I started some.”

There was, he said, one perquisite. “Reporting is the best school in the world to get a knowledge of human beings, human nature, and human ways. No other occupation brings a man into such familiar sociable relations with all grades and classes of people.”

On September 28, Sawyer and Twain went on a momentous bender. “Mark was as much sprung as I was,” Sawyer recalled, “and in a short time we owned the City, cobblestones and all.” They made the rounds of the Montgomery Street saloons, growing more expansive as they spent most of the night drinking brandy at the Blue Wing and the Capitol Saloon. “Toward mornin’ Mark sobered up a bit and we all got to tellin’ yarns,” Sawyer said. The sun was up by the time the two called it a night.

“The next day I met Mark down by the old Call office,” Sawyer continued. “He walks up to me and puts both hands on my shoulders. ‘Tom,’ he says, ‘I’m going to write a book about a boy and the kind I have in mind was just about the toughest boy in the world. Tom, he was just such a boy as you must have been....How many copies will you take, Tom, half cash?’”

Sawyer did not take him seriously. He got to the firehouse on Fourth Street and tried to sleep off his hangover in a back room. Twain went home, slept and then wrote his sister. “I would commence on my book,” he wrote. He had already spoken of his ambitious literary plan to write a novel to his brother Orion, cautioning him to say nothing of it.

Throughout the following year, 1865, Twain lived freelance assignment to freelance assignment. He had moved to Minna Street, an alley paralleling Market Street. Sawyer lived three blocks away. He had fallen in love with young Mary Bridget (records do not document her maiden name), and after they were married, the couple moved into 935 Mission Street. Sawyer set up housekeeping on the second floor and converted the ground floor into a saloon.

On Sunday, October 8, 1865, Twain was walking down Third Street when he was shaken off his feet. “The entire front of a tall four-story brick building in Third Street sprung outward like a door,” he wrote, “and fell sprawling across the street....” At Sawyer’s cottage, his antique firefighting memorabilia collection was smashed. Eleven days later, Twain, unable to pay off his debts, reached a decision. “I have a call to literature of a low order—i.e. humorous,” he wrote Orion and his wife, Mollie. “It is nothing to be proud of but it is my strongest suit.”

TWAIN FEIGNS CONFUSION—"A KIND

BUT NOT SAD FAREWELL”—

BEYOND THE GOLDEN GATE

*

On March 5, 1866, Twain wrote his mother and sister that he was to depart in two days for a reporting excursion to the Sandwich Islands (present-day Hawaii). “We shall arrive there in about twelve days. I am to remain there a month and ransack the islands, the great cataracts and the volcanoes completely and write twenty or thirty letters to the Sacramento Union for which they pay me as much money as I would get if I stayed at home.”

After he steamed back to California, reaching San Francisco in August, he visited the Turkish baths to see Sawyer. As he sweated his worries away, Twain studied the round-faced young firefighter. Sawyer had found happiness, and with a prosperous, popular bar, was helping to build a great city. Meanwhile, Twain was preparing for a lecture tour on the Sandwich Islands, to be delivered at stops in Nevada and California, concluding in San Francisco on December 10.

A crowd including California governor Frederick Low and Nevada governor Henry Blasdel gathered in front of Congress Hall on Bush Street to hear Twain’s talk. He intended to add final remarks summing up San Francisco, what it had been and would be. He would speak of its destiny. Now there were 20 blocks, 1,500 new homes and offices, fireproof buildings.

As he waited for the lecture to begin, Tom Sawyer wriggled in his seat next to Mary Bridget, his mind occupied by the $183 he owed in delinquent property taxes. At 8 p.m. the gaslights dimmed. Twain stepped to the podium. Solemn-faced, he shuffled a stack of ragged pages, dropping them in feigned confusion until he had the crowd laughing. “And whenever a joke did fall,” he recalled in Roughing It in 1872, “and their faces did split from ear to ear, Sawyer, whose hearty countenance was seen looming redly in the center of the second row, took it up, and the house was carried handsomely. The explosion that followed was the triumph of the evening. I thought that honest man Sawyer would choke himself.”

He seemed to be speaking directly to Sawyer when he said that the time was drawing near when prosperity lay upon the land. “I am bidding the old city and my old friends a kind, but not a sad farewell, for I know that when I see this home again, the changes that will have been wrought upon it will suggest no sentiment of sadness; its estate will be brighter, happier and prouder a hundred fold than it is this day. This is its destiny!”

Twain, who had just turned 31, was taking his leave of San Francisco. Sawyer pumped his hand and hugged him goodbye. They would never meet again.

Twain departed aboard the steamer America on December 15, leaving behind more friends than any newspaperman who had ever sailed out of the Golden Gate.

THE AUTHOR TELLS A STRETCHER—

HELMETS, BADGES AND BUGLES—

SAWYERS NAME IMMORTALIZED

*

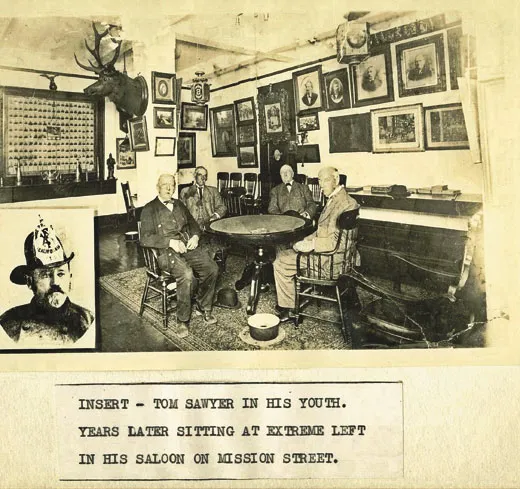

Sawyer presided over his saloon, and for 21 years, until 1884, held his civil-service job with the San Francisco Customs House. He also continued to serve as a part-time firefighter for many years, after volunteer units were disbanded and a paid fire department was created in 1866. In 1869, Sawyer had been seriously injured in the line of duty when an engine and hose cart overturned. Two fire horses excited by the frenzied clanging of the fire bell had snapped a harness as they dashed from the station. He convalesced at home with Mary Bridget and their three boys—Joseph, Thomas Jr., and William—and soon returned to battling blazes. Only around 1896, after turning 65, did he retire from the force.

In 1876, Twain published The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Thirty-seven when he began writing it, he completed 100 pages in 1873, but composed the rest in 1874 and 1875, when a friend, the author and Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells, read a draft. For the character of Sawyer, Twain would say only that he had drawn upon three boys. In 1923, Albert Bigelow Paine, who had published Twain’s approved biography in 1912, named them as John B. Briggs (who died in 1907), William Bowen (who died in 1893) and Twain. In a note to a young girl in 1907, Twain himself wrote, “I have always concealed it, but now I am compelled to confess that I am Tom Sawyer!” He also contradicted Roughing It, writing that “‘Sawyer’ was not the real name...of any person I ever knew, so far as I can remember….”

The great appropriator liked to pretend his characters sprang fully grown from his fertile mind. Yet the fireman had no doubts that he was the inspiration for the name of Tom Sawyer.

Viola Rodgers, a reporter at Twain’s old paper, the Call, interviewed Tom Sawyer on October 23, 1898. She was intrigued by what Twain had written in a postscript to the book: “Most of the characters that perform in this book still live and are prosperous and happy. Some day it may seem worthwhile to take up the story of the younger ones again and see what sort of men and women they turned out to be; therefore it will be wisest not to reveal any of that part of their lives at present.”

She reached the old-fashioned Mission Street saloon just to the east side of the Mint. “Over the door hangs a sign which reads ‘The Gotham—Tom Sawyer. Proprietor,’” she later wrote. “To a casual observer that name means no more than if it were ‘Jack Brown’ or ‘Tom Jones,’ but to Mark Twain it meant the inspiration for his most famous work. For the jolly old fireman sitting in there in an old fashioned haircloth chair is the original Tom Sawyer....This real, live, up-to-date Tom Sawyer spends his time telling stories of former days while he occasionally mixes a brandy and soda or a cocktail.” The walls were completely covered with helmets, belts, election tickets, badges, hooks, bugles, nozzles, mementos and other firefighting paraphernalia. “Next to his badges of his fire company, Tom Sawyer values his friendship with Mark Twain, and he will sit for hours telling of the pranks they used to play and of the narrow escapes they had from the police. He is fond of reminiscing and recalling the jolly nights and days he used to spend with Sam—as he always calls him.”

“You want to know how I came to figure in his books, do you?” Sawyer asked. “Well, as I said, we both was fond of telling stories and spinning yarns. Sam, he was mighty fond of children’s doings and whenever he’d see any little fellers a-fighting on the street, he’d always stop and watch ’em and then he’d come up to the Blue Wing and describe the whole doings and then I’d try and beat his yarn by telling him of the antics I used to play when I was a kid and say, ‘I don’t believe there ever was such another little devil ever lived as I was.’ Sam, he would listen to these pranks of mine with great interest and he’d occasionally take ’em down in his notebook. One day he says to me: ‘I am going to put you between the covers of a book some of these days, Tom.’ ‘Go ahead, Sam,’ I said, ‘but don’t disgrace my name.’”

“But [Twain’s] coming out here some day,” Sawyer added, “and I am saving up for him. When he does come there’ll be some fun, for if he gives a lecture I intend coming right in on the platform and have a few old time sallies with him.”

The nonfictional character died in the autumn of 1906, three and a half years before Twain. “Tom Sawyer, Whose Name Inspired Twain, Dies at Great Age,” the newspaper headline announced. The obituary said, “A man whose name is to be found in every worthy library in America died in this city on Friday....So highly did the author appreciate Sawyer that he gave the man’s name to his famous boy character. In that way the man who died Friday is godfather, so to speak, of one of the most enjoyable books ever written.”

Sawyer’s saloon was destroyed that same year—by fire.

Twain was more definite about the real-life model for Huckleberry Finn than Tom Sawyer. And he admitted that he had based Tom Sawyer’s Becky Thatcher on Laura Hawkins, who lived opposite the Clemens family on Hill Street in Hannibal Missouri, and modeled Sid Sawyer, Tom’s well-behaved half brother, on his lamented brother Henry.

Curiously, the claim that Twain was supposed to have named Tom Sawyer after his San Francisco acquaintance was well known in 1900, when the principals were alive, including Twain, Sawyer and probably several hundred San Franciscans who knew them both, and could have authenticated or challenged the claim. No one disputed it in San Francisco—nor did Twain. Sawyer himself never doubted that Twain named his first novel for him.