The Age of Peace

Maturing populations may mean a less violent future for many societies torn by internal conflict

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Japan-aged-population-631.jpg)

One overlooked benefit of aging populations may be the prospect of a more peaceful world.

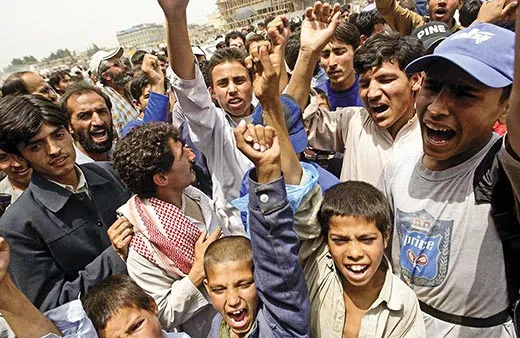

Demographers have found that developing nations with “youth bulges”—more than 40 percent of people between the ages of 15 and 29—are 2.5 times more prone to internal conflict, including terrorism, than countries with fewer young people, largely because of high unemployment combined with youthful exuberance and vulnerability to peers.

“The more young people you have, the more violence you have,” says Mark Haas, a political scientist at Duquesne University who has spent the past three years studying how aging patterns among major world powers will affect U.S. security. Between 1970 and 1999, he says, 80 percent of the world’s civil conflicts erupted in nations with substantial youth bulges. Today, those bulges are clustered in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Uganda, Yemen and Somalia.

But as youth bulges approach middle age, political stability often increases, researchers say. Richard Cincotta, a demographer who consults for the U.S. National Intelligence Council, cites Indonesia: “Political violence has declined in the westward islands,” which tend to be older, “while islands to the east, where the age structure is more youthful, remain politically unstable.” Cincotta also cites a decrease in political violence in Japan and South Korea—both rocked by student protests in the 1960s and ’70s—as their youth bulges dropped below 40 percent. Likewise, waning fertility rates, which have produced a decline in the youthful population in southern India, may have created an environment less supportive of Maoist insurgency groups that are active in the country’s northern and eastern states.

“If we know that youth bulges are a big source of violence, including terrorism, it’s good news if these youth bulges are receding,” Haas says.

Still, older is not always mellower. Not even a maturing population will settle down if accompanying economic gains aren’t shared, or if declining fertility rates don’t occur uniformly among different groups within a society. Ethnic divisions, in particular, can trump demography. The former Yugoslav republic, notes Cincotta and Haas, experienced years of brutal conflict between relatively mature populations.

In Pakistan and Iraq, the youth bulge won’t drop below 40 percent until 2023 and 2030, respectively. Afghanistan is another story. It has one of the world’s fastest-growing populations, with more than 50 percent of the population currently 15 to 29 years old. The United Nations does not project that age group to dip below 40 percent before 2050. “The demographic pyramid of Afghanistan right now,” Haas says, “is really frightening from a stability point of view.”

Carolyn O’Hara lives in Washington, D.C.