The American Ambassador Who Tried to Prevent Pearl Harbor

A new book explores the diplomatic efforts of Joseph C. Grew, who was assigned to Tokyo between 1932 and 1942

:focal(2033x1646:2034x1647)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/25/78/2578ed58-dd6b-4660-a098-93c3bf5910cd/gettyimages-514946364.jpg)

The ambassador woke, stirred by some faint shift. The clock said 1 a.m. Half asleep, he glanced out the porthole at the dark waters of Tokyo Bay, with Yokohama silhouetted beyond, so familiar after a week’s confinement aboard the anchored Asama Maru. A piece of driftwood slipped by, moving a bit too fast, then another moving faster.

He snapped alert: The Asama Maru was underway. After six and a half months of internment in the Tokyo embassy and a week aboard ship, the ambassador and his fellow Americans were finally headed home. The passengers included journalists, missionaries, businesspeople and diplomats, plus the few women and children who hadn’t been evacuated in the tense months before Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Some of the non-diplomats had been imprisoned, beaten or waterboarded as suspected spies. One imprisoned reporter lost his feet to frostbite and gangrene. A handful of passengers had told the ambassador that if negotiations for their release failed, they would kill themselves rather than return to land. But now Japan was disappearing in their wake.

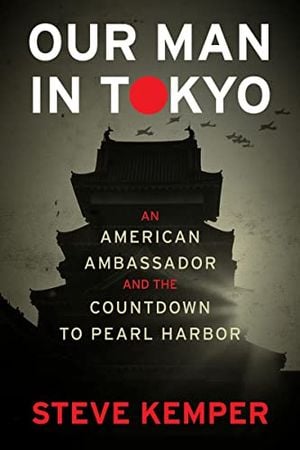

Our Man In Tokyo: An American Ambassador and the Countdown to Pearl Harbor

A gripping, behind-the-scenes account of the personalities and contending forces in Tokyo during the volatile decade that led to World War II, as seen through the eyes of the American ambassador who attempted to stop the slide to war.

It was June 25, 1942—10 years and 19 days after Joseph Clark Grew first set foot in Japan as ambassador. Grew was a legend in the State Department. By the time he boarded the Asama Maru, he had been in the foreign service for nearly 40 years in 14 posts, among them Cairo, Mexico City, St. Petersburg, Vienna and Berlin, where he closed the U.S. Embassy during World War I. After that, he served on the Peace Commission to Versailles. Following a stint in Washington, D.C., he became ambassador to Denmark, then Switzerland, before returning to Washington as second in command at the State Department. In 1927, he was named ambassador to Turkey, a tricky post. That’s where he got word in early 1932 that President Herbert Hoover wanted him as ambassador to the most difficult mission in the world at the time: Japan.

Most ambassadors remain nameless to the American public, but Grew became so well known that whenever he was home on leave, people stopped him on the street. His words and photo appeared constantly in newspapers and newsreels. He was handsome and athletic, more than six feet tall, with an emphatic mustache, swept-back salt-and-pepper hair, and bristling eyebrows above keen eyes. Time put him on its cover in 1934. In 1940, Life ran a long feature in which writer John Hersey, later famous for Hiroshima, called Grew “unquestionably the most important U.S. ambassador” and Tokyo the “most important embassy ever given a U.S. career diplomat.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4a/f9/4af91746-fa1b-4e1f-91ad-d2af20739e68/1-grew.jpg)

Grew spent ten years trying to preserve peace amidst assassinations, nationalist fanaticism, plots to overthrow the government, war fever stoked by a rabid press and international provocations by the swaggering Japanese military. After each fresh typhoon, he tried to find some way to rebuild diplomatic relations. Now, sailing home, he comforted himself with the knowledge that he had never stopped trying to halt, or at least slow down, the momentum toward war. Mere hours before bombs hit Pearl Harbor, he had driven to the home of the Japanese foreign minister at midnight with a last-minute appeal from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Emperor Hirohito. “I worked for peace up to the end,” Grew wrote.

During his six months of internment, he reviewed the past decade, especially the last year. He reexamined his diary and the dispatches to and from the State Department. He reread his correspondence with Roosevelt, whom he had known since their days at Groton and Harvard. He had sometimes guessed wrong, misread situations, made mistakes, but had always been willing to correct misperceptions or flawed assumptions. Had he missed something that might have altered events?

As always, he did his thinking through his fingertips, tapping away on his Corona typewriter. What came out was a thick document that recounted Japan’s rash belligerence and the replacement of a civilian government with unrestrained military ambition. He noted, once again, the synchronized buildup of a massive war machine with a propaganda campaign that demonized Western nations while exhorting all Japanese to sacrifice everything, including their lives, for the glory of their divine emperor.

But the Japanese weren’t the sole cause of the frustration marbling this document. Grew cataloged what he considered missteps by the White House and the State Department, lost opportunities to avert or delay tragedy. The State Department had often ignored his reports and rejected his recommendations, especially his urgent plea in the fall of 1941 for Roosevelt to accept the invitation of Japan’s prime minister, Fumimaro Konoe, to meet somewhere in the Pacific for a last-ditch attempt to prevent war. Grew cited telegrams sent to Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull warning that the American government was gravely misreading the mood in Japan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e2/b8/e2b818b2-062a-44ca-bd39-343011e53bb4/800px-fumimaro_konoe.jpeg)

“Japan may go all-out in a do-or-die effort, actually risking national hara-kiri,” he cabled on November 3, five weeks before Pearl Harbor. “Armed conflict with the United States,” he added, “might come with dangerous and dramatic suddenness.” The next day, he wrote in his diary, “That important telegram is on the record for all time.”

Even as his misgivings about U.S. policy grew, the ambassador faithfully conveyed that policy to the Japanese government. But after Pearl Harbor, he felt compelled to leave a frank record of his views. When he finished writing, he followed his usual practice with important dispatches, asking close subordinates in the embassy to critique it. All endorsed his analysis.

He thought of it as his final report from Tokyo and intended to deliver it to Roosevelt and Hull as soon as he reached America. Somewhere in the Atlantic, he added a 13-page cover letter to Roosevelt summarizing his view that the U.S. government had failed to do everything possible to delay war, partly because it had disregarded his reports about the true situation in Japan. “There are some things,” he wrote to Roosevelt, “that can be sensed by the man on the spot which cannot be sensed by those at a distance.”

On August 25, two months and 18,000 miles after the detainees left Japan, the Statue of Liberty rose into view, lit by the morning sun. Behind it soared the skyline of New York City. Someone onboard began singing “America the Beautiful.” Fifteen hundred voices joined in, many through tears.

Grew was the first passenger to debark, waving and smiling, dapper in a well-cut gray flannel suit. He talked to a scrum of reporters and spoke into a microphone for a newsreel in the accent of patrician Boston. “To be actually standing on the soil of our beloved country again,” he said, “gives us a sense of happiness far too deep and keen to describe in words.” Then he and his personal secretary, Robert Fearey, ducked into a limousine that took them straight to the station, where they boarded a train to Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/54/ab/54abc66d-5ee4-4561-83cc-c62c4765895a/asama_maru_arrives_in_los_angeles_on_her_maiden_voyage.jpeg)

The next morning, they drove from Grew’s Washington home to the State Department. The ambassador carried his confidential report. He was promptly shown in to see Hull. Fearey waited in the anteroom.

“About 25 minutes later,” recalled Fearey, “the secretary’s raised and clearly irate Tennessee accent penetrated the oaken door.” Hull was notorious for his volatile temper and colorful tirades. “I could not make out what he was saying,” continued Fearey, “but it was obvious that the meeting was not going well. Soon the door opened and Grew emerged looking somewhat shaken, with Hull nowhere in sight.”

Grew suggested an early lunch at the exclusive Metropolitan Club, where he was a member. They walked two blocks to it. Once seated there, Grew described how he had presented the gist of the report, then asked for an explanation about what bothered him most—the government’s rejection of Prime Minister Konoe’s proposal for a peace summit with Roosevelt. Hull hadn’t received any of this well.

“If you thought so strongly,” Hull said to Grew, “why didn’t you board a plane and come to tell us?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0b/24/0b247741-2b1d-41d5-a7de-e7514c7b62ff/service-pnp-hec-47100-47149v.jpeg)

Grew answered that he had sent a blizzard of urgent telegrams on the subject and often wondered if anyone even read them. He didn’t respond to the absurd idea of abandoning his post during a crisis for a long trip to Washington and back.

As Hull skimmed the report, his face grew progressively more “hardened and flushed.” He abruptly flung the pages back across the desk. “Mr. Ambassador,” he thundered, “either you promise to destroy this report and every copy you may possess, or we will publish it and leave it to the American people to decide who was right and who was wrong.”

Stunned, Grew said that destroying the report would violate his conscience and perhaps the historical record. Publishing it while the country was at war, however, might damage the public’s trust in the administration, an offense against Grew’s deep sense of patriotism. Hull told him to return with a decision tomorrow at ten o’clock.

The next morning, Grew and Fearey drove back to the State Department. Grew disappeared behind the big oak door. This time, Fearey didn’t hear Hull’s raised voice. After 30 minutes, the two men walked out, smiling and exchanging cordial goodbyes. Grew again suggested lunch at the Metropolitan. Fearey asked what had happened. Nothing much, said Grew, adding that neither he nor Hull had even mentioned the report, a statement difficult to believe after the previous day’s fireworks. He offered nothing more. Fearey was too junior to pry.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/64/1f/641f5592-ba7c-47ac-8e87-cae06588c522/service-pnp-cph-3c00000-3c02000-3c02300-3c02349v.jpeg)

Years later, Grew gave his papers to his beloved alma mater, Harvard. His archive comprises thousands of pages that include his diary (kept since 1911, including 6,000 pages during his Tokyo years alone), letters, speeches, dispatches, synopses of important conversations and news clippings. His final report, including all the supporting addenda, had grown to 276 pages. It is labeled “Dispatch No. 6018,” with the dateline “Tokyo, February 19, 1942.”

But the original document is missing. A typed note inserted by Grew into the bowdlerized version explains, “Upon submission of the [dispatch] in its final form, pages 13 to 146 inclusive are eliminated.” Grew evidently complied with Hull’s command to destroy all copies of the final report, but his typed insert makes clear he did so under protest. He also decided that his cover letter to Roosevelt was technically separate and therefore outside Hull’s order. The letter survives in the archive. At the top of it, handwritten in Grew’s scribble, is the notation “not sent.” At the point in the letter where he mentions the final report, he penciled in the margin, “destroyed at Mr. Hull’s request.” Grew obeyed his superior’s order but refused to clean up the crime scene.

No copies of the original report have ever turned up. Fearey, who had read it, searched for years. Yet Grew documented so much of his experience and thinking in other places—his diary, his letters, thousands of dispatches to the State Department, his memoirs Ten Years in Japan and Turbulent Era—that the final report survives like a palimpsest. So does its enticing, wrenching question: what if?

Grew knew the question was unanswerable. Our Man in Tokyo is about how he came to ask it—about the experiences of the man on the spot during ten years of intrigues, provocations and failed negotiations that preceded December 7, 1941. Grew is a lens into a decade of world-shaking history.

Excerpted from Our Man In Tokyo: An American Ambassador and the Countdown to Pearl Harbor by Steve Kemper. Published by Mariner Books. Copyright © 2022 Steve Kemper. All rights reserved.

Smithsonian Associates will host a live, online event with Steve Kemper on Monday, December 5, at 6:45 p.m. ET.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kemper_HighRes_2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kemper_HighRes_2.png)