The American Football League’s Foolish Club

Succeeding where previous leagues had failed, the AFL introduced an exciting brand of football forcing the NFL to change its entrenched ways

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1960-AFL-Championship-Game-631.jpg)

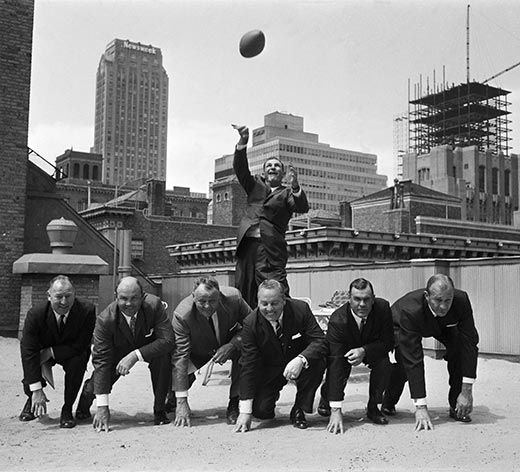

Having risked his reputation by un-retiring from a 10-year career in the established National Football League for the upstart American Football League, George Blanda clearly wasn't afraid to gamble. In the final quarter of the AFL championship game on New Year’s Day 1961, the stakes were high. Backed up on their own 12-yard line, it looked like the Los Angeles Chargers might get the ball back with time to take the lead. But the Houston Oilers quarterback knew his opponents were going to blitz. He looped a swing pass to Heisman Trophy-winning running back Billy Cannon, who then broke a tackle and outraced everybody to pay dirt, giving the Oilers a 24-16 lead and the title. “That was the big play that killed them,” recalls Blanda, now 82, of the game.

Blanda ended up throwing for 301 yards and three touchdowns, outdueling the Chargers’ quarterback, future congressman and vice presidential candidate Jack Kemp. He also kicked an 18-yard field goal and three extra points. More than 41 million people watched the broadcast on ABC and 32,183 showed up at Jeppesen Field, a converted high school stadium in Houston. Players on the Oilers earned $800 each for the victory.

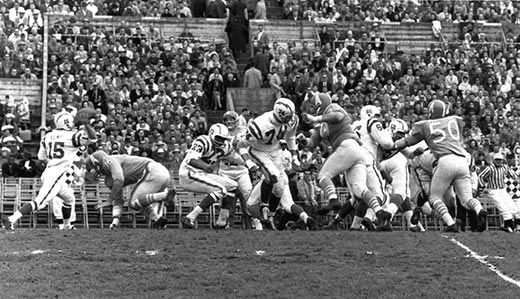

The game was typical of the high-risk, exciting brand of football the AFL showcased. While NFL games were often ball control affairs emphasizing the running game, the AFL aired it out, throwing downfield play after play, taking chance after chance. In the NFL championship game, played five days before the AFL game, the Philadelphia Eagles and Green Bay Packers passed 55 times for a total of 382 yards. The Oilers and Chargers combined for 73 passes and 472 yards. “Our goal was to score a lot of points, open up the game, and make it more viewable,” Blanda says.

Blanda threw for more touchdowns than he had during his NFL career in each of the seven seasons he was an AFL starter, including a high of 36 in 1961. He also threw 42 interceptions in 1962, which remains a record. "We took a lot of chances and threw a lot of interceptions," he says.

Former NFL executive Gil Brandt notes that for fans, even an unsuccessful deep pass play is more exciting than a run. Responsible for shepherding the NFL expansion Dallas Cowboys through their first season in 1960 as the team’s vice president for player personnel, Brandt, like others, figured the new league would soon fold, as other NFL challengers had. “They started from the back of nowhere. I didn’t think they ever would survive,” he says. “They did and all of the teams are still in operation. They’ve all done extremely well.”

The game and the entire 1960 season were vindication for the “Foolish Club.” That’s what the eight original AFL team owners called themselves because they were crazy enough to take on the firmly entrenched NFL. Among them were Texas millionaires Lamar Hunt and Bud Adams Jr., who had been refused entry into the NFL in 1959. Over the previous four decades other upstarts, including the All American Conference, had challenged the NFL. None were successful.

Perhaps the most lasting influence of the AFL is the offense conceived by Sid Gillman, the innovative Chargers’ coach, that used the passing game to set up the run, in contrast to the way football had been played for years. The descendants of Gillman’s coaching tree, including Bill Walsh, Al Davis, Chuck Noll, and Mike Holmgren, have won 20 Super Bowls combined.

The league’s legacy also can be seen in many of the innovations adopted by the NFL. The AFL put names on the back of players’ jerseys, made the scoreboard clock official (time had been kept on the field), offered the two-point conversion, and recruited African-American players, unlike some NFL teams. (The NFL’s Washington Redskins didn’t have a single black player the first year of AFL play and would not integrate until pressure from the federal government and commissioner Pete Rozelle forced team owner George Preston Marshall to trade for running back Bobby Mitchell) The AFL also played the first Thanksgiving Day game, an NFL tradition.

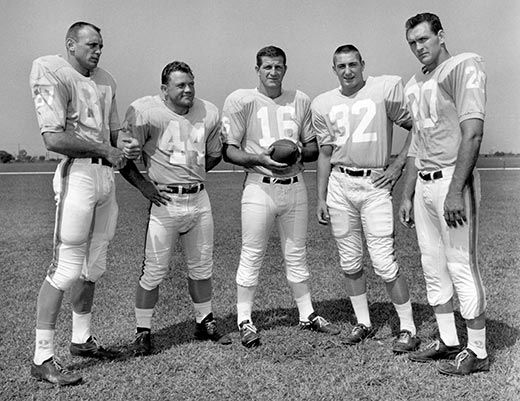

Blanda was typical of the so-called “NFL rejects” in the early AFL. He had retired before the 1959 NFL season after tiring of the Chicago Bears’ tight-fisted owner George Halas and was working as a trucking company sales manager. It turned out he had a few good years left, playing for the Oilers and then the Oakland Raiders. He retired in 1975 at age 48 after playing 26 seasons, more than anyone in history.

The New York Titans’ Don Maynard, another star who went on, like Blanda, to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, was a castoff from the New York Giants. Len Dawson languished five years in the NFL, starting two games, then became a superstar and future Hall of Famer with the Kansas City Chiefs.

Others, like Charlie Hennigan, who was coaching a Louisiana high school team and teaching biology when the Oilers offered a tryout, never had a shot in the established league. He’d played at tiny Northwestern State College in his native Louisiana and was undrafted by the NFL. He signed with the Oilers in 1960 for a $250 bonus and a $7,500 salary. “I was so happy,” recalls Hennigan, 74.”I was going to be making as much as the principal.”

He kept a pay stub from his $270.62-a-month teaching job in his helmet as a reminder of what he’d go back to if he failed. He didn’t. Hennigan may be the most prolific receiver not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In 1961, he set a single season record for reception yards that stood until 1995. In 1964, he became the second receiver to catch more than 100 passes in a season with 101, a record that lasted until 1992.

Blanda points out there were only 12 NFL teams with 33 players on a squad when the AFL began, meaning there were a lot of good athletes available. “I know the NFL people thought we were not much better than a junior college team,” Blanda says.”But we had a lot of great players in our league.”

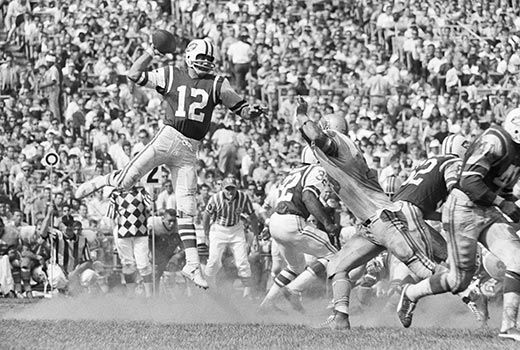

By the middle of the 1960s, the NFL was luring away as many players from the AFL as the AFL was from the NFL. The bidding war for players, which began when the AFL was formed (Brandt recalls the price for free agents went from $5,500 to $7,500 the first year and kept climbing) reached a peak in 1965 when the New York Jets signed Alabama quarterback Joe Namath to a three-year, $427,000 contract, the biggest deal ever for an athlete in a team sport.

That year, NBC signed a five-year, $36 million television deal with the AFL, far more than CBS was paying the NFL. The NFL responded by ordering CBS not to give AFL scores during telecasts. A year later, a gentlemen’s agreement between the leagues not to sign each other’s players was shattered when the New York Giants enticed star kicker Pete Gogolak from the Bills for a three-year, $96,000 contract. A bidding war ensued with several established NFL stars signing with the AFL.

Finally, the two leagues announced a merger in the summer of 1966. They would play the first AFL-NFL World Championship Game (the term “Super Bowl” was coined later) after the 1966 season. The NFL’s Green Bay Packers won the first two matchups, then the New York Jets and Kansas City Chiefs grabbed the next two, announcing loudly that the AFL was the NFL’s equal.

The rivalry hasn’t waned for Blanda and Hennigan, even though they draw NFL pension checks. They’re still AFL guys at heart.

“We were a better show than the NFL was,” Hennigan says. “They didn’t like us and they still don’t like us. And I don’t like them.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)