The Ax Murderer Who Got Away

In 1912, a family of six was murdered by ax in the little town of Villisca, Iowa. Might these killings be linked to nine other similar crimes?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120608042031Moores-c1905-web.jpg)

Shortly after midnight on June 10, 1912—one hundred years ago this week—a stranger hefting an ax lifted the latch on the back door of a two-story timber house in the little Iowa town of Villisca. The door was not locked—crime was not the sort of thing you worried about in a modestly prosperous Midwest settlement of no more than 2,000 people, all known to one another by sight—and the visitor was able to slip inside silently and close the door behind him. Then, according to a reconstruction attempted by the town coroner next day, he took an oil lamp from a dresser, removed the chimney and placed it out of the way under a chair, bent the wick in two to minimize the flame, lit the lamp, and turned it down so low it cast only the faintest glimmer in the sleeping house.

Still carrying the ax, the stranger walked past one room in which two girls, ages 12 and 9, lay sleeping, and slipped up the narrow wooden stairs that led to two other bedrooms. He ignored one, in which four more young children were sleeping, and crept into the room in which 43-year-old Joe Moore lay next to his wife, Sarah. Raising the ax high above his head—so high it gouged the ceiling—the man brought the flat of the blade down on the back of Joe Moore’s head, crushing his skull and probably killing him instantly. Then he struck Sarah a blow before she had time to wake or register his presence.

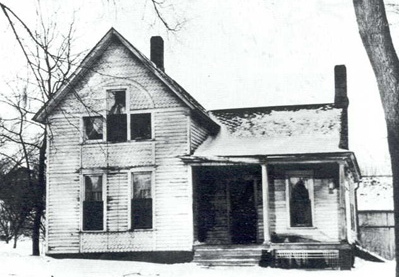

The Moore house in Villisca, 1912. One of the town’s larger and better-appointed properties, it still stands today and has been turned into Villisca’s premier tourist attraction. For a price, visitors can stay in the house overnight; there is no shortage of interested parties.

Leaving the couple dead or dying, the killer went next door and used the ax—Joe’s own, probably taken from where it had been left in the coal shed—to kill the four Moore children as they slept. Once again, there is no evidence that Herman, 11; Katherine, 10; Boyd, 7; or Paul, 5, woke before they died. Nor did the assailant or any of the four children make sufficient noise to disturb Katherine’s two friends, Lena and Ina Stillinger, as they slept downstairs. The killer then descended the stairs and took his ax to the Stillinger girls, the elder of whom may finally have awakened an instant before she, too, was murdered.

What happened next marked the Villisca killings as truly peculiar and still sends shivers down the spine a century after the fact. The ax man went back upstairs and systematically reduced the heads of all six Moores to bloody pulp, striking Joe alone an estimated 30 times and leaving the faces of all six members of the family unrecognizable. He then drew up the bedclothes to cover Joe and Sarah’s shattered heads, placed a gauze undershirt over Herman’s face and a dress over Katherine’s, covered Boyd and Paul as well, and finally administered the same terrible postmortem punishment to the girls downstairs before touring the house and ritually hanging cloths over every mirror and piece of glass in it. At some point the killer also took a two-pound slab of uncooked bacon from the icebox, wrapped it in a towel, and left it on the floor of the downstairs bedroom close to a short piece of key chain that did not, apparently, belong to the Moores. He seems to have stayed inside the house for quite some time, filling a bowl with water and–some later reports said–washing his bloody hands in it. Some time before 5 a.m., he abandoned the lamp at the top of the stairs and left as silently as he had come, locking the doors behind him. Taking the house keys, the murderer vanished as the Sunday sun rose red in the sky.

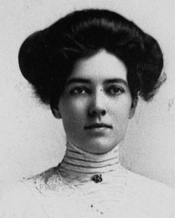

Lena and Ina Stillinger. Lena, the elder of the girls, was the only one who may have awoken before she died.

The Moores were not discovered until several hours later, when a neighbor, worried by the absence of any sign of life in the normally boisterous household, telephoned Joe’s brother, Ross, and asked him to investigate. Ross found a key on his chain that opened the front door, but barely entered the house before he came rushing out again, calling for Villisca’s marshal, Hank Horton. That set in train a sequence of events that destroyed what little hope there may have been of gathering useful evidence from the crime scene. Horton brought along Drs. J. Clark Cooper and Edgar Hough and Wesley Ewing, the minister of the Moore’s Presbyterian congregation. They were followed by the county coroner, L.A. Linquist, and a third doctor, F.S. Williams (who became the first to examine the bodies and estimate a time of death). When a shaken Dr Williams emerged, he cautioned members of the growing crowd outside: “Don’t go in there, boys; you’ll regret it until the last day of your life.” Many ignored the advice; as many as 100 curious neighbors and townspeople tramped as they pleased through the house, scattering fingerprints, and in one case even removing fragments of Joe Moore’s skull as a macabre keepsake.

The murders convulsed Villisca, particularly after a few clumsy and futile attempts to search the surrounding countryside for a transient killer failed to unearth a likely suspect. The simple truth was that there was no sign of the murderer’s whereabouts. He might have vanished back into his own home nearby; equally, given a head start of up to five hours in a town at which nearly 30 trains called every day, he might easily have made good his escape. Bloodhounds were tried without success; after that there was little for the townspeople to do but gossip, swap theories–and strengthen their locks. By sundown there was not a dog to be bought in Villisca at any price.

Dona Jones, daughter-in-law of Iowa state senator Frank Jones, was widely rumored in Villisca to have had an affair with Joe Moore.

The most obvious suspect may have been Frank Jones, a tough local businessman and state senator who was also a prominent member of Villisca’s Methodist church. Edgar Epperly, the leading authority on the murders, reports that the town quickly split along religious lines, the Methodists insisting on Jones’s innocence and the Moores’ Presbyterian congregation convinced of his guilt. Though never formally charged with any involvement in the murders, Jones became the subject of a grand jury investigation and a prolonged campaign to prove his guilt which destroyed his political career. Many townspeople were certain he used his considerable influence to have the case against him quashed.

There were at least two compelling reasons to believe that Jones had nursed a hatred of Joe Moore. First, the dead man had worked for him for seven years, becoming the star salesman of Jones’s farm-equipment business. But Moore had left in 1907–dismayed, perhaps, by his boss’s insistence on hours of 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., six days a week—and set himself up as a head-to-head rival, taking the valuable John Deere account with him. Worse, he was also believed to have slept with Jones’s vivacious daughter-in-law, a local beauty whose numerous affairs were well known in town thanks to her astonishingly indiscreet habit of arranging trysts over the telephone at a time when all calls in Villisca had to be placed through an operator. By 1912 relations between Jones and Moore had grown so cold that the they began to cross the street to avoid each other, an ostentatious sign of hatred in such a minuscule community.

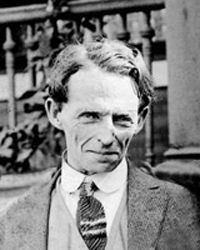

The Reverend Lyn Kelly, a markedly peculiar Presbyterian preacher, attended the Children’s Day service in Villisca at which the Moore children gave recitations, and later confessed to murdering the family—only to recant and claim police brutality.

Few people in Villisca believed that a man of Jones’s age and eminence—he was 57 in 1912—would have swung the ax himself, but in some minds he was certainly capable of paying someone else to wipe out Moore and his family. That was the theory of James Wilkerson, an agent of the renowned Burns Detective Agency, who in 1916 announced that Jones had hired a killer by the name of William Mansfield to murder the man who had humiliated him. Wilkerson—who made enough of a nuisance of himself to derail Jones’s attempts to secure re-election to the state senate, and who eventually succeeded in having a grand jury convened to consider the evidence he had gathered–was able to show that Mansfield had the right sort of background for the job: In 1914 he was the chief suspect in the ax murders of his wife, her parents and his own child in Blue Island, Illinois.

Unfortunately for Wilkerson, Mansfield turned out to have a cast-iron alibi for the Villisca killings. Payroll records showed that had been working several hundred miles away in Illinois at the time of the murders, and he was released for lack of evidence. That did not stop many locals—including Ross Moore and Joe Stillinger, father of the two Stillinger girls—from believing in Jones’s guilt. The rancor caused by Wilkerson lingered on in the town for years.

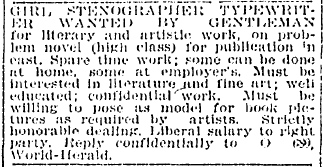

The advert that Lyn Kelly placed in the Omaha World-Herald. One respondent received a “lascivious” multi-page reply which told her she would be required to type in the nude.

For others, though, there was a far stronger–and far stranger– candidate for the ax man. His name was Lyn George Jacklin Kelly, and he was an English immigrant, a preacher and a known sexual deviant with well-recorded mental problems. He had been in the town on the night of the murders and freely admitted that he had left on a dawn train just before the bodies were discovered. There were things about Kelly that made him seem an implausible suspect—not least that he stood only 5-foot-2 and weighed 119 pounds—but in other ways he fit the bill. He was left-handed, and Coroner Linquist had determined from an examination of blood spatters in the murder house that the killer probably swung his ax that way. Kelly was obsessed with sex, and had been caught peering into windows in Villisca two days before the murders. In 1914, living in Winner, South Dakota, he would advertise for a “girl stenographer” to do “confidential work,” and that ad, placed in the Omaha World-Herald, would also specify that the successful candidate “must be willing to pose as model.” When a young woman named Jessamine Hodgson responded, she received in return a letter, described by a judge as “so obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy as to be offensive to this honorable court and improper to be spread upon the record thereof.” Amongst his milder instructions, Kelly told Hodgson that she would be required to type in the nude.

Convicted ax murderer Henry Lee Moore was the suspect favored by Department of Justice Special Agent Matthew McClaughry–who believed he committed a total of nearly 30 similar murders across the Midwest in 1911-12 .

Investigation soon made plain that there were links between Lyn Kelly and the Moore family. Most sinister, for those who believed in the little preacher’s guilt, was the fact that Kelly had attended the Children’s Day service held at Villisca’s Presbyterian church on the evening of the murders. The service had been organized by Sarah Moore, and her children, together with Lena and Ina Stillinger, had played prominent parts, dressed up in their Sunday best. Many in Villisca were willing to believe that Kelly had spotted the family in the church and become obsessed with them, and that he had spied on the Moore household as it went to bed that evening. The idea that the killer had lain in wait for the Moores to go to sleep was supported by some evidence; Linquist’s investigation had revealed a depression in some bales of hay stored in the family barn, and a knot hole through which the murderer could have watched the house while reclining in comfort. That Lena Stillinger had been found wearing no underwear and with her nightdress drawn up past her waist did suggest a sexual motive, but doctors found no evidence of that sort of assault.

It took time for the case against Kelly to get anywhere, but in 1917 another grand jury finally assembled to hear the evidence linking him with Lena’s murder. At first glance, the case against Kelly seemed compelling; he had sent bloody clothing to the laundry in nearby Macedonia, and an elderly couple recalled meeting the preacher when he alighted from a 5.19 a.m. train from Villisca that June 10 and being told that gruesome murders had been committed in the town—a hugely incriminating statement, since the preacher had left Villisca three hours before the killings were discovered. It also emerged that Kelly had returned to Villisca a week later and shown great interest in the murders, even posing as a Scotland Yard detective to obtain a tour of the Moore house. Arrested in 1917, the Englishman was repeatedly interrogated and eventually signed a confession to the murder in which he stated: “I killed the children upstairs first and the children downstairs last. I knew God wanted me to do it this way. `Slay utterly’ came to my mind, and I picked up the axe, went into the house and killed them.” This he later recanted, and the couple who claimed to have spoken to him on the morning after murders changed their story. With little left to tie him firmly to the killings, the first grand jury to hear Kelly’s case hung 11-1 in favor of refusing to indict him, and a second panel freed him.

Rollin and Anna Hudson were the victims of an ax murderer in Paola, Kansas, just five days before the Villisca killings.

Perhaps the strongest evidence that both Jones and Kelly were most likely innocent came not from Villisca itself but from other communities in the Midwest, where, in 1911 and 1912, a bizarre chain of ax murders seemed to suggest that a transient serial killer was at work. The researcher Beth Klingensmith has suggested that as many as 10 incidents that occurred close to railway tracks but in locations as far apart as Rainier, Washington, and Monmouth, Illinois, might form part of this chain, and in several cases there are striking similarities to the Villisca crime. The pattern, first pointed out in 1913 by Special Agent Matthew McClaughry of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (forerunner of the FBI), began with the murder of a family of six in Colorado Springs in September 1911 and continued with two further incidents in Monmouth (where the murder weapon was actually a pipe) and in Ellsworth, Kansas. Three and five people died in those attacks, and two more in Paola, Kansas, where someone murdered Rollin Hudson and his unfaithful wife just four days before the killings in Villisca. As far as McClaughry was concerned, the slaughter culminated in December 1912 with the brutal murders of Mary Wilson and her daughter Georgia Moore in Columbia, Missouri. His theory was that Henry Lee Moore, Georgia’s son and a convict with a history of violence, was responsible for the whole series.

It is not necessary to believe that Henry Lee Moore was a serial killer to consider that the string of Midwest ax murders have intriguing similarities that may tie the Villisca massacre to other crimes. Moore is now rarely considered a good suspect; he was certainly an unsavory character—released from a reformatory in Kansas shortly before the ax murders began, arrested in Jefferson City, Missouri, shortly after they ended, and eventually convicted of the Columbia murders. But his motive in that case was greed–he planned to obtain the deeds to his family house–and it is rare for a wandering serial killer to return home and kill his own family. Nonetheless, analysis of the sequence of murders—and several others that McClaughry did not consider—yields some striking comparisons.

Blanche Wayne, of Colorado Springs, may have been the first victim of a Midwest serial murderer. She was killed in her bed in September 1911 by an ax man who heaped bedclothes on her head and stopped to wash his hands, leaving the weapon at the scene.

The use of an ax in almost every case was perhaps not so remarkable in itself; while there certainly was an unusual concentration of ax killings in the Midwest at this time, almost every family in rural districts owned such an implement, and often left it lying in their yard; as such, it might be considered a weapon of convenience. Similarly, the fact that the victims died asleep in their beds was likely a consequence of the choice of weapon; an ax is nearly useless against a mobile target. Yet other similarities among the crimes are much harder to explain away. In eight of the 10 cases, the murder weapon was found abandoned at the scene of the crime; in as many as seven, there was a railway line nearby; in three, including Villisca, the murders took place on a Sunday night. Just as significant, perhaps, four of the cases—Paolo, Villisca, Rainier and a solitary murder that took place in Mount Pleasant, Iowa—featured killers who covered their victims’ faces, three murderers had washed at the scene, and at least five of the killers had lingered in the murder house. Perhaps most striking of all, two other homes (those of the victims of the Ellsworth and Paola murders) had been lit by lamps in which the chimney had been laid aside and the wick bent down, just as it had been at Villisca.

Whether or not all these murders really were connected remains a considerable puzzle. Some pieces of evidence fit patterns, but others do not. How, for example, might a stranger to Villisca have so uneeringly located Joe and Sarah Moore’s bedroom by low lamp light, ignoring the children’s rooms until the adults were safely dead? On the other hand, the use of the flat of the ax blade to strike the fatal initial blows does suggest the murderer had previous experience–any deep cut made with the sharp edge of the blade was more likely to result in the ax becoming lodged in the wound, making it far riskier to attack a sleeping couple. And the Paola murders have striking similarities with Villisca aside from the killer’s use of a carefully adapted lamp; in both cases, for example, odd incidents occurred the same night that suggest the killer may have attempted to strike twice. In Villisca, at 2.10 a.m. on the night of the murder, telephone operator Xenia Delaney heard strange footsteps approaching up the stairs, and an unknown hand tried her locked door, while in Paola, a second family was awakened in the dead of night by a sound that turned out to be a lamp chimney falling to the floor. Rising hurriedly, the occupants of that house were in time to see an unknown man escaping through a window.

Perhaps the spookiest of all such similarities, however, was the strange behavior of the unknown murderer of William Showman, his wife, Pauline, and their three children in Ellsworth, Kansas in October 1911. In the Ellsworth case, not only was a chimneyless lamp used to illuminate the murder scene, but a little heap of clothing had been placed over the Showmans’ telephone.

A Western Electric Model 317 telephone, one of the most popular on sale in the Midwest in 1911-12. Note the phone’s startlingly “human” features.

Why bother to muffle a phone that was highly unlikely to ring at one in the morning? Perhaps, as one student of the murders posits, for the same reason that the Villisca murderer took such great pains to cover the faces of his victims, and then went around the murder house carefully draping torn clothing and cloths over all the mirrors and all the windows: because he feared that his dead victims were somehow conscious of his presence. Might the Ellsworth killer have covered the telephone out of the same desperate desire to ensure that, nowhere in the murder house, was there a pair of eyes still watching him?

Sources

Beth H. Klingensmith. “The 1910s Ax Murders: An Overview of the McClaughry Theory.” Emporia State University Research Seminar, July 2006; Nick Kowalczyk. “Blood, Gore, Tourism: The Ax Murderer Who Saved a Small Town.” Salon.com, April 29, 2012; Roy Marshall. Villisca: The True Account of the Unsolved Mass Murder That Stunned The Nation. Chula Vista : Aventine Press, 2003; Omaha World-Herald, June 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 1912; December 27, 1913; June 10, 2012.

Several bloggers offer thoughtful insights into the Midwest ax murders. For the Villisca case, The 1912 Villisca Axe Murders Blog is a good place to start, and there was also occasional coverage at CLEWS. Meanwhile, Getting the Axe covers the whole apparent sequence of 1911-12 ax killings, with only a minor focus on the Villisca case itself.

Villisca: The True Account of the Unsolved Mass Murder That Stunned The Nation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)