The Battle of Bull Run: The End of Illusions

Both North and South expected victory to be glorious and quick, but the first major battle signaled the long and deadly war to come

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bull-run-battlefield-631.jpg)

Cannon boomed, brass bands serenaded and ladies tossed bouquets as Jefferson Davis arrived in Richmond on May 29, 1861, to make it the capital of the Confederate States of America. He had set out from the original capital at Montgomery, Alabama, soon after Virginia seceded from the Union six days earlier. Along the way, jubilant well-wishers slowed his train and he crossed the James River into Richmond far behind schedule. It was a scene wholly unlike President-elect Abraham Lincoln’s arrival in Washington the previous February, when he sneaked into the city at dawn in a curtained sleeping car because of threats of assassination as he passed through Baltimore. Richmond welcomed Davis as if he personally were going to smite the Yankees and drive them from Virginia soil.

To a cheering crowd, he said, “I know that there beats in the breasts of Southern sons a determination never to surrender, a determination never to go home but to tell a tale of honor....Give us a fair field and a free fight, and the Southern banner will float in triumph everywhere.”

Unlike Davis’ Mississippi and the other cotton states of the Deep South, Virginia, the most populous state below the Mason-Dixon line, had been reluctant to leave the Union of its fathers. The Richmond convention that debated secession leaned strongly against it; a country lawyer and West Point graduate named Jubal Early spoke for the majority when he warned that the convention could decide “the existence and the preservation of the fairest fabric of government that was ever erected....We ought not to act in hot haste, but coolly deliberate in view of the grave consequences.”

But after the first guns at Fort Sumter, when Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion, the convention reversed itself. Opinion swung so sharply that the result of the May 23 referendum confirming the convention’s decision was a foregone conclusion. More than five months after South Carolina became the first state to depart the Union, Virginia followed. As a result, the proud, conservative Old Dominion would be the bloodiest battleground of the Civil War—and the first and final objective of all that slaughter was the capital, the very symbol of Southern resistance, the city of Richmond.

At first, there had been brave talk in Dixie of making Washington the capital of the Confederacy, surrounded as it was by the slave states of Maryland and Virginia. Federal troops had been attacked by a mob in Baltimore, and Marylanders had cut rail and telegraph lines to the North, forcing regiments headed for Washington to detour by steaming down the Chesapeake Bay. Washington was in a state of nerves; officials fortified the Capitol and the Treasury against feared invasion. Richmond was alarmed by rumors that the Union gunboat Pawnee was on its way up the James River to shell the city into flames. Some families panicked, believing an Indian tribe was on the warpath. Militiamen rushed to riverside and aimed cannon downstream. But the Pawnee never came.

North and South, such rumors pursued rumors, but soon the preliminaries, real and imagined, were either resolved or laughed away. The stage was set for war, and both sides were eager for a quick and glorious victory.

The society widow Rose O’Neal Greenhow was well known for her Southern sentiments, but in her home just across Lafayette Square from the White House she entertained Army officers and congressmen regardless of their politics. Indeed, one of her favorites was Henry Wilson, a dedicated abolitionist and future vice president from Massachusetts who had replaced Jefferson Davis as chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. Greenhow, sophisticated and seductive, listened carefully to everything her admirers said. Soon she would be sending notes across the Potomac encoded in a cipher left with her by Thomas Jordan, who had resigned his Army commission and gone south.

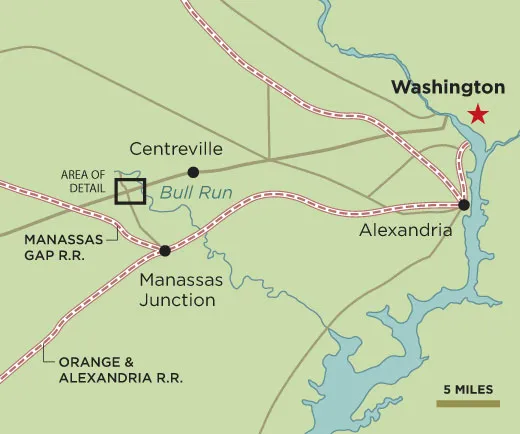

As summer began, Jordan was adjutant of the Confederate Army under Brig. Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, a dashing Louisianan. Beauregard, who had become the Confederacy’s premier hero by commanding the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April, was now gathering brigades to protect the vital rail junction at Manassas, little more than 25 miles west-southwest of Washington.

On July 4, Lincoln asked a special session of Congress for 400,000 troops and $400 million, with legal authority “for making this contest a short, and a decisive one.” He expressed not only the hope, but also the expectation of most officials in Washington. Many of the militia outfits rolling in from the North had signed on in April for just 90 days, assuming they could deal with the uppity Rebels in short order. Day after day, a headline in the New York Tribune blared, “Forward to Richmond! Forward to Richmond!” a cry that echoed in all corners of the North.

The most notable voice urging restraint came from the most experienced soldier in the nation, Winfield Scott, general in chief of the U.S. Army, who had served in uniform since the War of 1812. But at 74, Scott was too decrepit to take the field and too weary to resist the eager amateurs of war as they insisted that the public would not tolerate delay. Scott turned over field command to Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell, who was headquartered at Robert E. Lee’s abandoned Arlington mansion. On July 16, the reluctant McDowell left Arlington and started the Union Army of the Potomac westward.

The Confederates knew what was coming, and when. On July 10, a beautiful 16-year-old girl named Betty Duval had arrived at Beauregard’s lines and shaken from her long, dark hair a coded dispatch from Rose Greenhow, saying that McDowell would take the offensive in mid-month. Six days later Greenhow sent another courier with a note reporting that the Union Army was on the march.

Beauregard had grandiose ideas of bringing in reinforcements from west and east to outflank McDowell, attack him from the rear, crush the Yankees and proceed to “the liberation of Maryland, and the capture of Washington.” But as McDowell’s army advanced, Beauregard faced reality. He had to defend Manassas Junction, where the Manassas Gap Railroad from the Shenandoah Valley joined the Orange & Alexandria, which connected to points south, including Richmond. He had 22,000 men, McDowell about 35,000. He would need help.

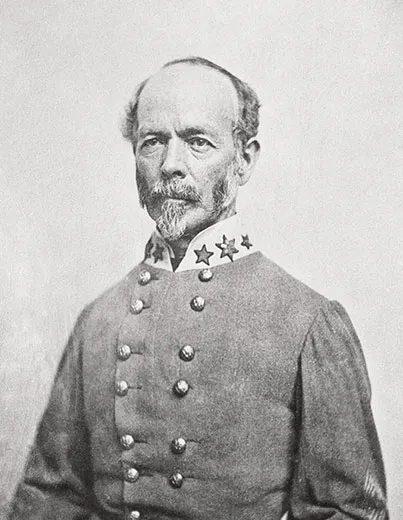

At the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston commanded about 12,000 Confederates blocking Northern entry into that lush farmland and invasion route. He faced some 18,000 Federals under 69-year-old Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson, another veteran of the War of 1812. Patterson’s assignment was to prevent Johnston from threatening Washington and from moving to help Beauregard. In early July, Beauregard and Johnston, both expecting attack, were urgently seeking reinforcements from each other.

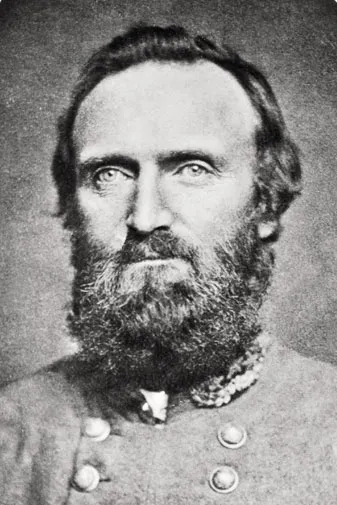

That contest ended on July 17. Beauregard informed President Davis that after skirmishing along his advance lines, he was pulling his troops back behind the little river called Bull Run, about halfway between Centreville and Manassas. That night, Davis ordered Johnston to hurry “if practicable” to aid Beauregard. Since Patterson had unaccountably pulled his Union force away down the valley, Johnston quickly issued marching orders. Screened by Col. Jeb Stuart’s cavalry, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson led his Virginia brigade out of Winchester at midday on July 18. The imminent battlefield was 57 miles away, and already the first guns had sounded along Bull Run.

Beauregard spread his brigades on a nearly ten-mile front behind the winding stream, from near Stone Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike down to Union Mills. They concentrated at a series of fords that crossed the 40-foot-wide river. Bull Run has steep banks and is deep in spots, and would have slowed even experienced troops. The soldiers of 1861, and many of their officers, were still novices.

McDowell was 42 years old, a cautious, teetotaling officer who had served in Mexico but spent most of his career on staff duty. With green troops and his first major command, he did not want to attack the Confederates head-on. He intended to swing east and strike Beauregard’s right flank, crossing Bull Run where it was closest to the junction. But after reaching Centreville on July 18, he rode out to inspect the ground and decided against it. Before departing, he ordered Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler, commanding his lead division, to probe the roads ahead—not to start a battle, but to make the Rebels think the army was aiming directly for Manassas. Tyler exceeded his orders: after spotting the enemy across the stream and swapping artillery rounds, he pushed his infantry at Blackburn’s Ford, testing the defenses. The Rebels, commanded there by Brig. Gen. James Longstreet, hid until the Federals were close. Then they let loose a storm of musketry that sent Tyler’s troops fleeing back toward Centreville.

In both directions, this short, sharp clash was vastly exaggerated. Back in Washington, Southern sympathizers crowding the barrooms along Pennsylvania Avenue celebrated what they already called “the Battle of Bull Run.” One Union general told the Times of London correspondent William Howard Russell that the news meant “we are whipped,” while a senator quoted General Scott as announcing “a great success.... We ought to be in Richmond by Saturday”—just two days later. Swarms of civilians rushed out from the capital in a party mood, bringing picnic baskets and champagne, expecting to cheer the boys on their way. One of the less cheerful scenes they encountered was the Fourth Pennsylvania Infantry and the Eighth New York Battery walking away on the brink of battle because their 90-day enlistments were up. For the next two days, McDowell stayed put, resupplying and planning. It was a fateful delay.

Soon after Johnston’s troops departed Winchester on July 18, he issued a communiqué to every regiment. Beauregard was being attacked by “overwhelming forces,” he wrote. “Every moment now is precious...for this march is a forced march to save the country.” Out front, Jackson’s brigade forded the Shenandoah River and toiled up the Blue Ridge through Ashby Gap before bedding down that night at the hamlet of Paris. From there it was six-plus miles downhill to the Manassas Gap Railroad station at Piedmont (now Delaplane). Arriving about 8:30 a.m., the troops jammed into freight cars, and overworked locomotives took eight more hours to bring them the last 34 miles to Manassas Junction.

The rest of Johnston’s army straggled in over the next 24 hours. Johnston himself reached Manassas about midday. To head off confusion, he asked President Davis to make clear that he was senior in rank to Beauregard. Later the two officers agreed that since Beauregard was more familiar with the immediate situation, he would retain command at the tactical level while Johnston managed the overall campaign.

That day, July 20, two opposing generals sat writing orders that, if carried through, would send their attacking armies pinwheeling around each other. Beauregard intended to strike McDowell’s left, throwing most of his army toward Centreville to cut the Federals off from Washington. McDowell prepared to cross Bull Run above Stone Bridge and come down on Beauregard’s left. His plan looked good on paper, but did not account for the arrival of Johnston’s reinforcements. Beauregard’s plan was sound in concept, but not in detail: it told which brigades would attack where, but not exactly when. He woke Johnston to endorse it at 4:30 a.m. on Sunday, July 21. By then McDowell’s army was already moving.

Tyler’s division marched toward Stone Bridge, where it would open a secondary attack to distract the Confederates. Meanwhile Union Brig. Gens. David Hunter and Samuel Heintzelman started their divisions along the Warrenton Turnpike, then made a wide arc north and west toward an undefended ford at Sudley Springs, two miles above the bridge. They were to cross Bull Run there and drive down the opposite side, clearing the way for other commands to cross and join a mass assault on Beauregard’s unsuspecting left flank.

The going was slow, as McDowell’s brigades bungled into each other and troops groped along dark, unscouted roads. McDowell himself was sick from some canned fruit he had eaten the night before. But hopes were high.

In the 11th New York Infantry, known as the Zouaves, Pvt. Lewis Metcalf heard “the latest news, of which the very latest seemed to be that General [Benjamin] Butler had captured Richmond and the Rebels had been surrounded by General Patterson,” he later wrote. “All that we had to do was to give Beauregard a thrashing in order to end all the troubles.” When they slogged past blankets strewn on the roadside by sweltering troops ahead of them, the Zouaves assumed the bedding had been thrown away by fleeing Confederates and “set up a lively shout.”

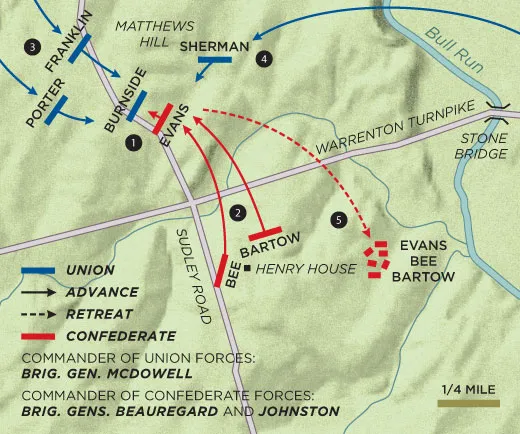

About 5:30 that morning, the first shell, a massive Federal 30-pounder, whanged through the tent of a Confederate signal station near Stone Bridge without hurting anybody. That round announced Tyler’s advance, but the Confederates would not detect McDowell’s main effort for three more hours—until Capt. Porter Alexander, far back at Beauregard’s command post, spotted through his spyglass a flash of metal far beyond the turnpike. Then he picked out a glitter of bayonets nearing Sudley Springs. He quickly sent a note to Beauregard and flagged a signal to Capt. Nathan Evans, who was posted with 1,100 infantry and two smoothbore cannon at the far end of the Confederate line, watching Stone Bridge. “Look out for your left,” he warned. “You are flanked.”

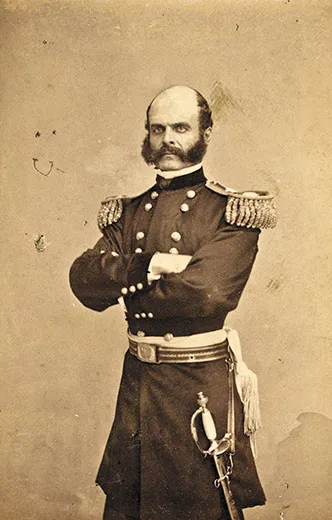

Without waiting for orders, Evans rushed across the turnpike with two of his regiments and faced north to block the threatening Federals. Union Col. Ambrose Burnside’s brigade, leading Hunter’s division, crossed at Sudley Springs near 9:30 after an approach march of more than ten miles. There Burnside ordered a stop for water and rest, giving Evans time to position his skimpy defenders in a strip of woods along Matthews Hill. When the Yankees came within about 600 yards, Evans gave the order to open fire.

Burnside advanced close behind his skirmishers, followed by Col. Andrew Porter’s brigade. Soon after the first burst of fire, Burnside encountered David Hunter, riding back seriously wounded, who told him to take command of the division. Evans’ men fought doggedly as the much heavier Union force pressed them back toward the turnpike. Confederate Brig. Gen. Barnard Bee, ordered to the left by Beauregard, started setting a defensive line near what is now called the Henry House, on a hill just south of the turnpike. But when Evans pleaded for help, Bee took his brigade forward to join him. Col. Francis Bartow’s Georgia brigade moved up beside them. After an hour’s hard combat, Heintzelman’s Union division arrived. He sent Col. William B. Franklin’s brigade ahead, and the Union attack started to stretch around Evans’ line. Crossing near Stone Bridge, Col. William Tecumseh Sherman’s brigade joined the offensive. Assailed on both sides, Evans, Bee and Bartow’s men broke back for nearly a mile, staggering across Henry House Hill.

During this rising tumult, Johnston and Beauregard were near Mitchell’s Ford, more than four miles away. For two hours, they waited to hear the planned Confederate move against the Union left flank. But it never materialized. The would-be lead brigade hadn’t gotten Beauregard’s order, and others listened in vain for its advance. It was about 10:30 when Beauregard and Johnston finally realized the noise on their far left was the real battle.

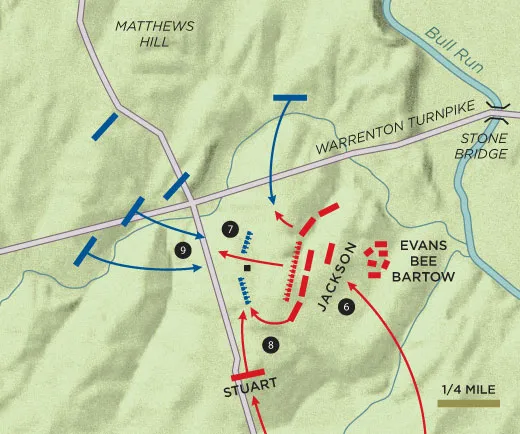

Quickly directing more troops that way, they galloped toward the firing. When they reached Henry House, Jackson was bringing his brigade up through the disorganized troops falling back. Unless he held here, the Yankees could sweep down into the Confederates’ rear and collapse their whole army. Jackson threw up a defensive line just behind the crest of the hill, where the Federals could not see it as they gathered to charge. A bullet or shell fragment painfully wounded his left hand as he rode back and forth steadying his men, siting artillery pieces and asking Jeb Stuart to protect the flank with his cavalry. Barnard Bee, trying to revive his shaken brigade, pointed and shouted words that would live long after him:

“There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”

Whether Bee said those exact words or not—they were among his last—there and then Jackson acquired the nickname by which he will always be known. He earned it in the next few hours, as more reinforcements hurried from the rear, sent ahead by Johnston and directed into place by Beauregard. McDowell pushed two batteries of regular U.S. Army cannon far forward to pound Jackson’s left. Stuart, watching that flank, warned Jackson and then charged, his horsemen scattering the infantry protecting the Yankee guns. Suddenly the 33rd Virginia regiment came out of the brush and let loose a volley that swept the cannoneers away. “It seemed as though every man and horse of that battery just laid right down and died right off,” a civilian witness said.

The Confederates grabbed the Federal guns and turned them against the attackers, but in fierce seesaw fighting, the Yankees temporarily took them back. Beauregard’s horse was shot from under him. Heintzelman was wounded as he drove his men ahead. Three times the Federals fought within yards of Jackson’s line and were thrown back by a sheet of fire. When that last effort wavered, Beauregard took the offensive. Jackson threw his troops forward, ordering them to “Yell like furies!”—and they did, thus introducing the Rebel yell as a weapon of war. Francis Bartow was killed and Bee was mortally wounded as the Rebels surged ahead.

The battle had turned, but it would turn again, and yet again.

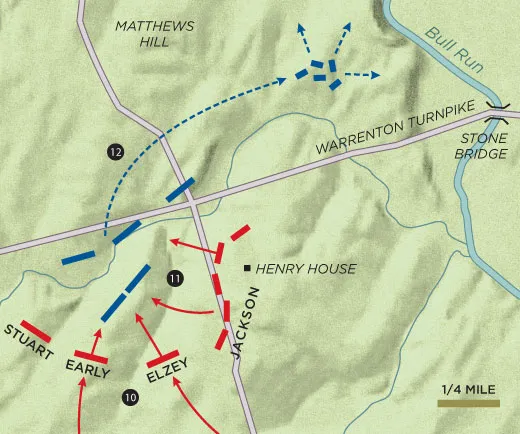

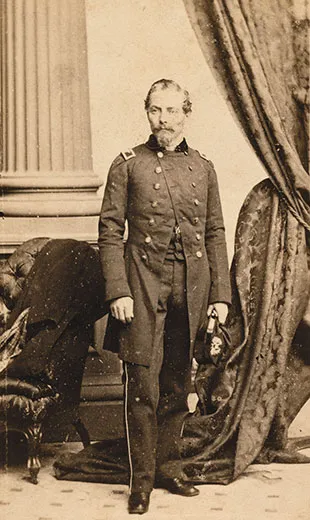

In the chaos of driving the Federals downhill toward the turnpike, the Confederates exposed both their flanks. McDowell sent more troops at them, and pushed back up the hill. But in doing so, he exposed his own flank. At about 4 o’clock, two new Rebel brigades, under Brig. Gen. Kirby Smith and Col. Jubal Early, suddenly appeared from the rear. Smith, just arrived from the Shenandoah Valley, was seriously wounded almost immediately. Led by Col. Arnold Elzey, his troops kept moving and stretched the Confederate line to the left. Then came Early—in hot haste, now thoroughly committed to Virginia’s cause—swinging his brigade still wider around the Union flank.

That did it.

Struck by this fresh wave of Rebels, McDowell’s exhausted troops on that side started falling back. Seeing them, Beauregard raised a cheer and waved his whole line forward. The Confederates charged again, sending the Federals reeling back toward Bull Run. McDowell and Burnside tried and failed to halt them. At first the retreat was deliberate, as if the men were simply tired of fighting—as the historian John C. Ropes wrote, they “quietly but definitively broke ranks and started on their homeward way.” But Stuart’s cavalry harried them, and as they recrossed beyond Stone Bridge, Rebel cannon zeroed in on the turnpike. Then, according to Capt. James C. Fry of McDowell’s staff, “the panic began...utter confusion set in: pleasure-carriages, gun-carriages, and ambulances...were abandoned and blocked the way, and stragglers broke and threw aside their muskets and cut horses from their harness and rode off on them.” Congressman Alfred Ely of New York, among the civilians who had come out to enjoy the show, was captured in the stampede and barely escaped execution by a raging South Carolina colonel, who was restrained by Captain Alexander.

As Rebel artillery harassed McDowell’s army, men “screamed with rage and fright when their way was blocked up,” wrote Russell, the British correspondent. “Faces black and dusty, tongues out in the heat, eyes staring....Drivers flogged, lashed, spurred and beat their horses....At every shot a convulsion...seized upon the morbid mass.”

McDowell himself was just as frank, if not as descriptive. After trying to organize a stand at Centreville, he was swept along by his fleeing army. Pausing at Fairfax that night, he fell asleep in the midst of reporting that his men were without food and artillery ammunition, and most of them were “entirely demoralized.” He and his officers, he wrote, agreed that “no stand could be made this side of the Potomac.”

The dark, stormy morning of July 22 found thousands of McDowell’s men stumbling into Washington, soaked and famished, collapsing in doorways. The sight was “like a hideous dream,” Mary Henry, daughter of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, wrote in her diary. News of the rout inspired a panic: Rebels about to march into Washington! But the Rebels were nowhere near. Beauregard followed the retreat into positions he had held a week earlier, but his army was too disorganized to make a serious effort against the capital itself.

Thus ended the “Forward to Richmond!” campaign of 1861.

Bull Run—or Manassas, as Southerners call it, preferring to name Civil War battles for towns instead of watercourses—was a fierce battle, but not huge compared with those to come later. Counts vary, but the Union lost about 460 men killed, 1,125 wounded and 1,310 missing, most of those captured. The Confederates suffered about 390 killed, 1,580 wounded—and only 13 missing, because they occupied the field. Altogether, both sides lost about 4,900—fewer than a fifth of the casualties counted when they fought on the same ground a year later, and fewer than a tenth of those at Gettysburg in 1863. Regardless of numbers, the psychological effect on both sides was profound.

Jefferson Davis arrived at Manassas after the contest was decided and set off celebrations in Richmond with a message saying, “We have won a glorious though dear-bought victory. Night closed on the enemy in full flight and closely pursued.” His speeches en route back, plus rumors from the front, made it sound as if he had gotten there just in time to turn the tide of battle. “We have broken the back bone of invasion and utterly broken the spirit of the North,” the Richmond Examiner exulted. “Henceforward we will have hectoring, bluster and threat; but we shall never get such a chance at them again on the field.” Some of Beauregard’s soldiers, feeling the same way, headed home.

A more realistic South Carolina official said the triumph was exciting “a fool’s paradise of conceit” about how one Rebel could lick any number of Yankees. Among Union troops, he told diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, the rout would “wake every inch of their manhood. It was the very fillip they needed.”

Most of the North woke up Monday morning to read that the Union had won: news dispatches filed when McDowell’s troops were driving the Confederates back had gone out from Washington, and War Department censors temporarily blocked later accounts. Lincoln, first buoyed and then struck hard by reports from the front, had stayed awake all Sunday night. When the truth came, his cabinet met in emergency session. Secretary of War Simon Cameron put Baltimore on alert and ordered all organized militia regiments to Washington. Generals and politicians competed in finger-pointing. Although McDowell with his green troops had very nearly won at Bull Run, after such a disaster he clearly had to go. To replace him, Lincoln summoned a 34-year-old Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who had won a series of minor clashes in western Virginia.

After days of alarm among citizens and public drunkenness among many of the Union’s disheartened soldiers, calm returned and the North looked ahead. Few there could agree at first with the anonymous Atlantic Monthly correspondent who wrote that “Bull Run was in no sense a disaster...we not only deserved it, but needed it....Far from being disheartened by it, it should give us new confidence in our cause.” But no one could doubt the gravity of the situation, that “God has given us work to do not only for ourselves, but for coming generations of men.” Thus all the North could join in vowing that “to gain that end, no sacrifice can be too precious or too costly.” Not until the following spring would McClellan take the rebuilt Army of the Potomac again into Virginia, and not for another three springs would the immensity of that sacrifice be realized.

Ernest B. Furgurson has written four books on the Civil War, most recently Freedom Rising. He lives in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)