Where Did the Term “Gerrymander” Come From?

Elbridge Gerry was a powerful voice in the founding of the nation, but today he’s best known for the political practice with an amphibious origin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/c5/43c5300d-0d38-433c-b637-91d01a70539e/the_gerry-mander_edit-wr.png)

Long and thin, the redrawn state senate district in Massachusetts stretched from near Boston to the New Hampshire border, where it hooked east along the Merrimack River to the coast. It sliced up Essex County, a political stronghold for the Federalist Party – all by design of its ascendant political rival, the Democratic-Republicans. It worked: the freakishly shaped district elected three Democratic-Republicans that year, 1812, breaking up the county’s previous delegation of five Federalist senators.

It wasn’t the first time in American history that political machinations were behind the drawing of district boundaries, but it would soon become the most famous.

Gerrymandering, the politicians’ practice of drawing district lines to favor their party and expand their power, is nearly as old as the republic itself. Today, we see it in Ohio’s “Lake Erie Monster” and Pennsylvania’s “Goofy Kicking Donald Duck.” But where did the name come from, and who was the namesake for the much-maligned process?

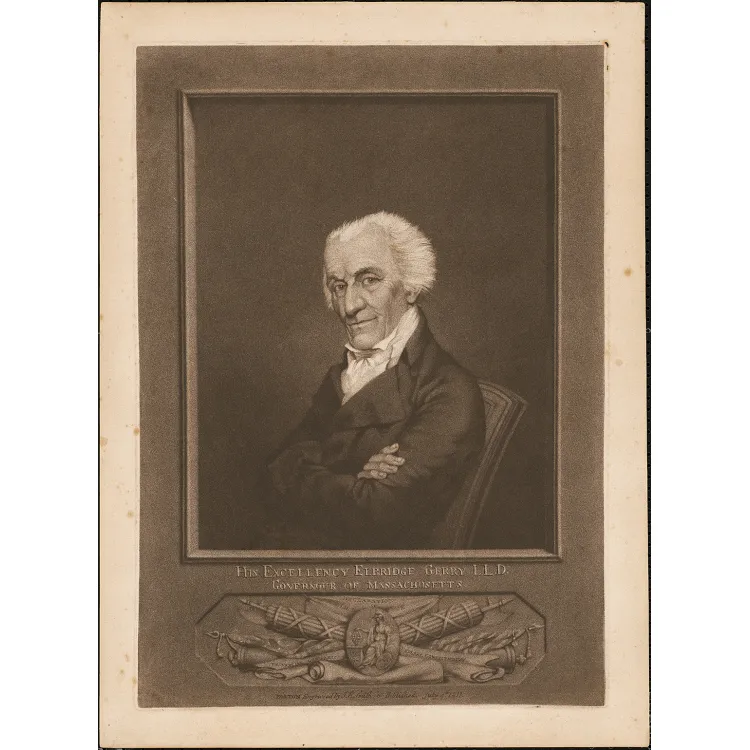

Elbridge Gerry, the governor who signed the bill creating the misshapen Massachusetts district, was a Founding Father: signer of the Declaration of Independence, reluctant framer of the Constitution, congressman, diplomat, and the fifth vice-president. Well-known in his day, Gerry was a wild-eyed eccentric and an awkward speaker, a trusted confidant of John Adams and a deep (if peculiar) thinker. He could also be a dyspeptic hothead—a trait that got the better of him when he signed the infamous redistricting bill.

A merchant’s son from the port town of Marblehead, Massachusetts, Gerry had wanted a different kind of fame—the immortality that comes with founding a nation. Elected to the Continental Congress in December 1775, Gerry lobbied his fellow delegates to declare independence from Great Britain. “If every Man here was a Gerry,” John Adams wrote in July 1776, “the Liberties of America would be safe against the Gates of Earth and Hell.”

But Gerry was also a “a nervous, birdlike little person,” wrote biographer George Athan Billias in his 1976 book, Elbridge Gerry: Founding Father and Republican Statesman. He stammered and had an odd habit of “contracting and expanding the muscles of his eye.” Colleagues respected Gerry’s intelligence, gentlemanliness, attention to detail, and hard work, but his maverick political views and personality sometimes hurt his judgment. According to Adams, he had an “obstinacy that will risk great things to secure small ones.”

That contrary streak defined Gerry’s role at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He spent its first two months arguing for less democracy in the new government than his colleagues were willing to support. For instance, Gerry argued against directly electing congressmen to the House of Representatives. In the convention’s second half, he took a different tack, arguing that the proposed central government would be too powerful.

Gerry refused to sign the Constitution—“as complete an aristocracy as ever was framed,” he complained – in part because he thought the standing army and the powerful Senate could become tyrannical. He became an Anti-Federalist, arguing that the Constitution had gotten the balance of power between states and the national government wrong. Gerry’s peers, and some historians, have dismissed his stance at the convention as inconsistent. But Billias argues that Gerry stayed true to his principles in Philadelphia. An “Old Republican,” Gerry feared any concentration of power and thought a republic had to balance centralized authority, the aristocracy, and the common people.

Even in dissent, Gerry did his part as a framer. He successfully argued for Congress’ power to override presidential vetoes. Though his push to add a Bill of Rights didn’t win over his fellow delegates, it later won over the country and the new Congress – where Gerry served as a leading anti-Federalist from 1789 to 1793, before serving President Adams in 1798 as a diplomat in France. Those contributions to the early United States, not gerrymandering, would’ve been Gerry’s legacy had he not come out of retirement to lead Massachusetts’ Democratic-Republicans in the 1810 gubernatorial election.

Though Gerry resisted joining a political party in the 1790s, in the 1800s he cast his lot with this new party, which supported a less centralized government and favored France over Britain in foreign policy. Like many Democratic-Republicans, Gerry came to believe that the Federalist opposition were too close to the British and secretly wanted to restore the monarchy.

At age 65, Gerry ran for governor, motivated by “his obsessive fears about various conspiracies underway to wreck the republic,” according to Billias. In his 1810 inaugural address, Gerry called for an end to partisan warfare between his Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists. But as the United States edged toward war with Great Britain in 1811, Gerry decided that Federalists’ protests against President James Madison’s foreign policy had turned near-treasonous. Gerry replaced Federalists in state government jobs with Democratic-Republicans, got his attorney general to prosecute Federalist newspaper editors for libel, and seized control of the Federalist-dominated Harvard College board.

Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans, who controlled the legislature, redrew the state’s Senate districts to benefit their party. Until then, senatorial districts had followed county boundaries. The new Senate map was so filled with unnatural shapes, Federalists denounced them as “carvings and manglings.”

Gerry signed the redistricting bill in February 1812 – reluctantly, if his son-in-law and first biographer, James T. Austin, is to be believed. “To the governour the project of this law was exceedingly disagreeable,” Austin wrote in The Life of Elbridge Gerry in 1829. “He urged to his friends strong arguments against its policy as well as its effects. … He hesitated to give it his signature, and meditated to return it to the legislature with his objections.” But back then, Austin claims, precedent held that Massachusetts governors didn’t veto laws unless they were unconstitutional.

But Gerry’s Federalist opponents saw the bill as another injury from his partisan vendetta. They responded with a satire so piercing, it has overshadowed all of Gerry’s other accomplishments in history.

The word “gerrymander” was coined at a Boston dinner party hosted by a prominent Federalist in March 1812, according to an 1892 article by historian John Ward Dean. As talk turned to the hated redistricting bill, illustrator Elkanah Tisdale drew a picture map of the district as if it were a monster, with claws and a snake-like head on its long neck. It looked like a salamander, another dinner guest noted. No, a “Gerry-mander,” offered poet Richard Alsop, who often collaborated with Tisdale. (An alternate origin story, which Dean found less credible, credited painter Gilbert Stuart, famed portraitist of George Washington, with drawing the monster on a visit to a newspaper office.)

Tisdale’s drawing, headlined “The Gerry-mander,” appeared in the Boston Gazette of March 26, 1812. Below it, a fanciful satire joked that the beast had been born in the extreme heat of partisan anger—the “many fiery ebullitions of party spirit, many explosions of democratic wrath and fulminations of gubernatorial vengeance within the year past.”

The gerrymander did its job, giving the Democratic-Republicans a bigger state Senate majority in Massachusetts’ April 1812 election, even though the Federalists actually got more votes statewide. But it couldn’t help Gerry, who lost the statewide popular vote for governor to Federalist challenger Caleb Strong.

President Madison awarded Gerry’s party loyalty with a consolation prize: the vice-presidency. Gerry joined Madison’s successful presidential ticket later in 1812. In his almost two years as vice-president, Gerry attended countless parties in official Washington and handled Democratic-Republicans’ patronage requests. He died, after complaining of chest pains, on November 23, 1814, at age 70.

It didn’t take long for Gerry’s namesake to take hold. By the 1820s, to “gerrymander” was already in wide circulation, according to H.L. Mencken’s The American Language. It entered Webster’s Dictionary in 1864 – and according to Mencken, the reason it wasn’t added earlier may have been because Noah Webster’s family was friendly with Gerry’s widow.

It’d be easy – too easy – to connect Gerry’s role in gerrymandering to his most famous comment at the Constitutional Convention, “The evils we experience flow from an excess of democracy.” Actually, across his long career, Gerry took principled stands for the Revolution, the American republic, limited government, and the Bill of Rights. But when his fears became obsessions, he overreacted and compromised his principles.

It’s an injustice that Gerry is best remembered for gerrymandering. It’s also a cautionary tale about the importance of sticking to one’s values in an era of partisan warfare.