The Case of the Sleepwalking Killer

The evidence against Albert Tirrell was lurid and damning—until Rufus Choate, a protegé of the great Daniel Webster, agreed to come to the defense

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rufus_Choate_header.jpg)

Rufus Choate approached his client just before the bang of the gavel, when Albert J. Tirrell was sitting in the dock, 22 years old and on trial for his life. It was March 24, 1846, three months after his arrest in the gruesome murder of his mistress. The defendant wore an olive coat with gilt buttons and a placid expression, looking indifferent to the gaze of the spectators. Choate leaned over the rail, raked long, skinny fingers through his thicket of black curls, and asked, “Well, sir, are you ready to make a strong push with me today?”

“Yes,” Tirrell replied.

“Very well,” Choate said. “We will make it.”

Within the week, the pair also made legal history.

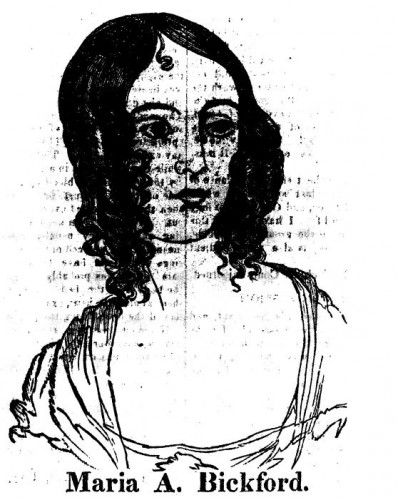

By then all of Boston knew the facts of the case, reported in breathlessly lurid detail by the penny press. Around 4:30 a.m. on October 27, 1845, the body of Mrs. Mary Ann Bickford (also called Maria Bickford), age 21, was found in a “disreputable” boardinghouse on Cedar Lane in the Beacon Hill neighborhood. She lay on her back in her nightgown, nearly decapitated, her neck wound measuring six inches long and three inches deep. The room was clogged with smoke; someone had set fire to the bed. A bloodstained razor was found at its foot. The victim’s hair was singed, her skin charred. Part of one ear was split open and missing an earring. A man’s vest and a cane were spattered with blood. Albert Tirrell, who had been seen with the victim earlier that night, was nowhere to be found. One witness spotted him bargaining with a livery stable keeper. He was “in a scrape,” he reportedly said, and had to get away.

He drove south to the house of some relatives in the town of Weymouth, who hid him from police and gave him money to flee the state. The following day he headed north into Canada and wrote to his family from Montreal, announcing his plans to sail to Liverpool. Bad weather forced the crew to turn back, and instead he boarded a ship in New York City bound for New Orleans. After receiving a tip that the fugitive was headed their way, authorities in Louisiana arrested Tirrell on December 5, while he was aboard a vessel in the Gulf of Mexico. Boston newspapers identified the captured man as “Albert J. Tirrell, gentleman, of Weymouth.”

Albert Tirrell and Mary Bickford had scandalized Boston for years, both individually and as a couple, registering, as one observer noted, “a rather high percentage of moral turpitude.” Mary, the story went, married James Bickford at 16 and settled with him in Bangor, Maine. They had one child, who died in infancy. Some family friends came to console her and invited her to travel with them to Boston. Like Theodore Dreiser’s protagonist Carrie Meeber, fifty years hence, Mary found herself seduced by the big city and the sophisticated living it seemed to promise. “While in the city she appeared delighted with everything she saw,” James Bickford said, “and on her return home expressed a desire to reside permanently in Boston.” She became, he added, “dissatisfied with her humble condition” and she fled to the city again, this time for good.

Mary Bickford sent her husband a terse note:

I cannot let you know where I am, for the people where I board do not know that I have got a husband. James, I feel very unsteady, and will consent to live with you and keep house; but you must consent for me to have my liberty.”

James came to Boston at once, found Mary working in a house of ill repute on North Margin Street and returned home without her. She moved from brothel to brothel and eventually met Tirrell, a wealthy and married father of two. He and Mary traveled together as man and wife, changing their names whenever they moved, and conducted a relationship as volatile as it was passionate; Mary once confided to a fellow boarder that she enjoyed quarreling with Tirrell because they had “such a good time making up.”

On September 29, 1845, he was indicted on charges of adultery, an offense the press described as “some indelicacies with a young woman,” and eluded arrest for weeks. After his capture and arraignment, numerous friends and relatives, including his young wife, besieged the prosecutor with letters requesting a stay of proceedings in the hope that he might be reformed. His trial was postponed for six months. Tirrell came to court, posted bond and rushed back to Mary at the boardinghouse on Cedar Lane, where the owners charged exorbitant rents to cohabitating unmarried couples, and where Mary would soon be found dead.

One of the first journalistic reports of the death of Mary Ann Bickford. From the Boston Daily Mail.

Tirrell retained the services of Rufus Choate, legal wunderkind and erstwhile United States senator from Massachusetts, an antebellum Johnnie Cochran renowned for his velocity of speech. He once spoke “the longest sentence known to man” (1,219 words) and made his mentor, Daniel Webster, weep during a talk titled “The Age of the Pilgrims, the Heroic Period of Our History.” Choate derived much of his courtroom strategy from Webster, drawing particular inspiration from his performance at the criminal trial of a client charged with robbery. Webster’s defense was based on offense; he impugned the character of the alleged victim, suggesting that he’d staged an elaborate sham robbery in order to avoid paying debts. Webster’s alternative narrative persuaded the jurors, who found his client not guilty.

Choate kept that case in mind while plotting his defense of Tirrell, and considered an even more daring tactic: contending that Tirrell was a chronic sleepwalker. If he killed Mary Bickford, he did so in a somnambulistic trance and could not be held responsible. Choate never divulged the genesis of this strategy, but one anecdote suggests a possibility. Henry Shute, who would later become a judge and well-known writer for The Saturday Evening Post, was a clerk in the law office of Charles Davis and William Whitman, two of Choate’s close friends. Choate stopped by often to play chess, and visited one afternoon shortly after agreeing to defend Tirrell. The famous lawyer noticed Shute reading Sylvester Sound, the Somnambulist, by the British novelist Henry Cockton. He asked to have a look. “Choate became interested, then absorbed,” Shute recalled. “After reading intently a long time he excused himself, saying, ‘Davis, my mind is not on chess today,’ and rising, left the office.” It was an unprecedented approach to a murder defense, but one that Choate believed he could sell.

On the first day of the trial, prosecutor Samuel D. Parker called numerous witnesses who helped establish a strong circumstantial case against Tirrell, but certain facets of testimony left room for doubt. The coroner’s physician conceded that Mary Bickford’s neck wound could have been self-inflicted. A woman named Mary Head, who lived near the boardinghouse, testified that on the morning of the murder Tirrell came to her home and rung the bell. When she answered he made a strange noise, a sort of gargle captured in his throat, and asked, “Are there some things here for me?” Mary was frightened by his “strange state, as if asleep or crazy.” The oddest recollection came from Tirrell’s brother-in-law, Nathaniel Bayley, who said that when Tirrell arrived in Weymouth he claimed to be fleeing from the adultery indictment. When Bayley informed him of the murder, Tirrell seemed genuinely shocked.

Rufus Choate allowed one of his junior counsel, Anniss Merrill, to deliver the opening argument for the defense. Merrill began, in homage to Daniel Webster, by maligning Mary’s character, repeating the possibility that she cut her own throat and positing that suicide was “almost the natural death of persons of her character.” Furthermore, Tirrell had been an honorable and upstanding gentleman until he met the deceased. “She had succeeded, in a wonderful manner, in ensnaring the prisoner,” Merrill insisted. “His love for her was passing the love ordinarily borne by men for women. She for a long time had held him spellbound by her depraved and lascivious arts.” It was an argument that resonated with the moralistic culture of early Victorian America, playing into fears about the growing commercialization of urban prostitution. City dwellers who witnessed a proliferation of dance halls and “fallen women” distributing calling cards on street corners could easily be persuaded that Mary was as villainous as the man who had killed her.

Merrill next introduced the issue of somnambulism, what he acknowledged was a “peculiar” and “novel” line of defense. “Alexander the Great penned a battle in his sleep,” he said. “La Fontaine wrote some of his best verses while in the same unconscious state; Condillac made calculations. Even Franklin was known to have arose and finished, in his sleep, a work that he had projected before going to bed.… Evidence will be produced to show that it had pleased Almighty God to afflict the prisoner with this species of mental derangement.”

One by one Tirrell’s family and friends recounted strange ways he’d behaved. He began sleepwalking at the age of six, and the spells had increased in frequency and severity with each passing year. He forcibly grabbed his brother, pulled down curtains and smashed windows, yanked a cousin out of bed and threatened him with a knife. While in this state he always spoke in a shrill, trembling voice. Their testimony was corroborated by Walter Channing, dean of Harvard Medical School, who testified that a person in a somnambulistic state could conceivably rise in the night, dress himself, commit a murder, set a fire and make an impromptu escape.

On the morning of the trial’s fourth day, spectators swarmed the courtroom eager to hear Rufus Choate—that “great galvanic battery of human oratory,” as the Boston Daily Mail called him. He began by ridiculing the prosecution’s case, pausing for dramatic effect after each resounding no:

How far does the testimony lead you? Did any human being see the prisoner strike the blow? No. Did any human being see him in that house after nine o’clock the previous evening? No. Did any human being see him run from the house? No. Did any human being see him with a drop of blood upon his hands? No. Can anyone say that on that night he was not laboring under a disease to which he was subject from his youth? No. Has he ever made a confession of the deed? To friend or thief taker, not one word.”

One stenographer later expressed the difficulty in capturing Choate’s thoughts: “Who can report chain lighting?”

During the last hour of his six-hour speech, Choate focused on the issue of somnambulism, stressing that 12 witnesses had testified to his client’s strange condition without challenge or disproof. “Somnambulism explains… the killing without a motive,” he argued. “Premeditated murder does not.” Here he approached the jury and lowered his voice. The courtroom hushed. “In old Rome,” he concluded, “it was always practice to bestow a civic wreath on him who saved a citizen’s life; a wreath to which all the laurels of Caesar were but weeds. Do your duty today, and you may earn that wreath.”

The jury deliberated for two hours and returned a verdict of not guilty. Spectators leapt to their feet and applauded while Albert Tirrell began to sob, his first display of emotion throughout the ordeal. Afterward he sent a letter to Rufus Choate asking the lawyer to refund half his legal fees, on the ground that it had been too easy to persuade the jury of his innocence.

Sources:

Books: Daniel A. Cohen, Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace: New England Crime Literature and the Origins of American Popular Culture, 1674-1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993; Silas Estabrook, The Life and Death of Mrs. Maria Bickford. Boston, 1846; Silas Estabrook, Eccentricities and Anecdotes of Albert John Tirrell. Boston, 1846; Edward Griffin Parker, Reminiscences of Rufus Choate: the Great American Advocate. New York: Mason Brothers, 1860; Barbara Meil Hobson, Uneasy Virtue: The Politics of Prostitution and the American Reform Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Articles: “Parker’s Reminiscences of Rufus Choate.” The Albany Law Journal, July 2, 1870; “Trial of Albert John Tirrell.” Prisoner’s Friend, April 1, 1846; ‘Somnambulism.” Prisoner’s Friend, September 9, 1846; “Continuation of Tirrell’s Trial.” The New York Herald, March 27, 1846; “Eminent Legal Rights.” Boston Daily Globe, August 27, 1888; “In the Courtroom with Rufus Choate.” Californian, December 1880; Vol. II, No. 12; “A Brief Sketch of the Life of Mary A. Bickford.” Prisoner’s Friend, December 17, 1845; “Arrest of Albert J. Tirrell.” Boston Cultivator, December 27, 1845; “Rufus Choate and His Long Sentences.” New York Times, September 15, 1900.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)