The Changing Definition of African-American

How the great influx of people from Africa and the Caribbean since 1965 is challenging what it means to be African-American

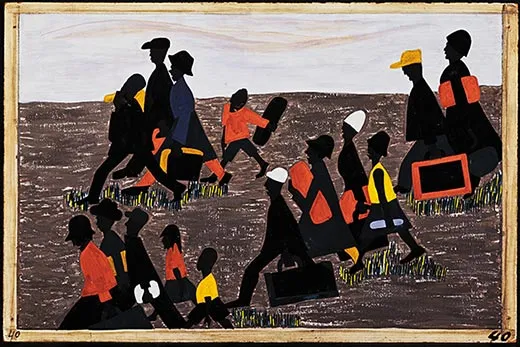

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Presence-of-Mind-Jacob-Lawrence-Migration-Series-631.jpg)

Some years ago, I was interviewed on public radio about the meaning of the Emancipation Proclamation. I addressed the familiar themes of the origins of that great document: the changing nature of the Civil War, the Union army’s growing dependence on black labor, the intensifying opposition to slavery in the North and the interplay of military necessity and abolitionist idealism. I recalled the longstanding debate over the role of Abraham Lincoln, the Radicals in Congress, abolitionists in the North, the Union army in the field and slaves on the plantations of the South in the destruction of slavery and in the authorship of legal freedom. And I stated my long-held position that slaves played a critical role in securing their own freedom. The controversy over what was sometimes called “self-emancipation” had generated great heat among historians, and it still had life.

As I left the broadcast booth, a knot of black men and women—most of them technicians at the station—were talking about emancipation and its meaning. Once I was drawn into their discussion, I was surprised to learn that no one in the group was descended from anyone who had been freed by the proclamation or any other Civil War measure. Two had been born in Haiti, one in Jamaica, one in Britain, two in Ghana, and one, I believe, in Somalia. Others may have been the children of immigrants. While they seemed impressed—but not surprised—that slaves had played a part in breaking their own chains, and were interested in the events that had brought Lincoln to his decision during the summer of 1862, they insisted it had nothing to do with them. Simply put, it was not their history.

The conversation weighed upon me as I left the studio, and it has since. Much of the collective consciousness of black people in mainland North America—the belief of individual men and women that their own fate was linked to that of the group—has long been articulated through a common history, indeed a particular history: centuries of enslavement, freedom in the course of the Civil War, a great promise made amid the political turmoil of Reconstruction and a great promise broken, followed by disfranchisement, segregation and, finally, the long struggle for equality.

In commemorating this history—whether on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, during Black History Month or as current events warrant—African- Americans have rightly laid claim to a unique identity. Such celebrations—their memorialization of the past—are no different from those attached to the rituals of Vietnamese Tet celebrations or the Eastern Orthodox Nativity Fast, or the celebration of the birthdays of Christopher Columbus or Casimir Pulaski; social identity is ever rooted in history. But for African-Americans, their history has always been especially important because they were long denied a past.

And so the “not my history” disclaimer by people of African descent seemed particularly pointed—enough to compel me to look closely at how previous waves of black immigrants had addressed the connections between the history they carried from the Old World and the history they inherited in the New.

In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, which became a critical marker in African-American history. Given opportunity, black Americans voted and stood for office in numbers not seen since the collapse of Reconstruction almost 100 years earlier. They soon occupied positions that had been the exclusive preserve of white men for more than half a century. By the beginning of the 21st century, black men and women had taken seats in the United States Senate and House of Representatives, as well as in state houses and municipalities throughout the nation. In 2009, a black man assumed the presidency of the United States. African-American life had been transformed.

Within months of passing the Voting Rights Act, Congress passed a new immigration law, replacing the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which had favored the admission of northern Europeans, with the Immigration and Nationality Act. The new law scrapped the rule of national origins and enshrined a first-come, first-served principle that made allowances for the recruitment of needed skills and the unification of divided families.

This was a radical change in policy, but few people expected it to have much practical effect. It “is not a revolutionary bill,” President Lyndon Johnson intoned. “It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives.”

But it has had a profound impact on American life. At the time it was passed, the foreign-born proportion of the American population had fallen to historic lows—about 5 percent—in large measure because of the old immigration restrictions. Not since the 1830s had the foreign-born made up such a tiny proportion of the American people. By 1965, the United States was no longer a nation of immigrants.

During the next four decades, forces set in motion by the Immigration and Nationality Act changed that. The number of immigrants entering the United States legally rose sharply, from some 3.3 million in the 1960s to 4.5 million in the 1970s. During the 1980s, a record 7.3 million people of foreign birth came legally to the United States to live. In the last third of the 20th century, America’s legally recognized foreign-born population tripled in size, equal to more than one American in ten. By the beginning of the 21st century, the United States was accepting foreign-born people at rates higher than at any time since the 1850s. The number of illegal immigrants added yet more to the total, as the United States was transformed into an immigrant society once again.

Black America was similarly transformed. Before 1965, black people of foreign birth residing in the United States were nearly invisible. According to the 1960 census, their percentage of the population was to the right of the decimal point. But after 1965, men and women of African descent entered the United States in ever-increasing numbers. During the 1990s, some 900,000 black immigrants came from the Caribbean; another 400,000 came from Africa; still others came from Europe and the Pacific rim. By the beginning of the 21st century, more people had come from Africa to live in the United States than during the centuries of the slave trade. At that point, nearly one in ten black Americans was an immigrant or the child of an immigrant.

African-American society has begun to reflect this change. In New York, the Roman Catholic diocese has added masses in Ashanti and Fante, while black men and women from various Caribbean islands march in the West Indian-American Carnival and the Dominican Day Parade. In Chicago, Cameroonians celebrate their nation’s independence day, while the DuSable Museum of African American History hosts a Nigerian Festival. Black immigrants have joined groups such as the Egbe Omo Yoruba (National Association of Yoruba Descendants in North America), the Association des Sénégalais d’Amérique and the Fédération des Associations Régionales Haïtiennes à l’Étranger rather than the NAACP or the Urban League.

To many of these men and women, Juneteenth celebrations—the commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States—are at best an afterthought. The new arrivals frequently echo the words of the men and women I met outside the radio broadcast booth. Some have struggled over the very appellation “African-American,” either shunning it—declaring themselves, for instance, Jamaican-Americans or Nigerian-Americans—or denying native black Americans’ claim to it on the ground that most of them had never been to Africa. At the same time, some old-time black residents refuse to recognize the new arrivals as true African-Americans. “I am African and I am an American citizen; am I not African-American?” a dark-skinned, Ethiopian-born Abdulaziz Kamus asked at a community meeting in suburban Maryland in 2004. To his surprise and dismay, the overwhelmingly black audience responded no. Such discord over the meaning of the African-American experience and who is (and isn’t) part of it is not new, but of late has grown more intense.

After devoting more than 30 years of my career as a historian to the study of the American past, I’ve concluded that African-American history might best be viewed as a series of great migrations, during which immigrants—at first forced and then free—transformed an alien place into a home, becoming deeply rooted in a land that once was foreign, even despised. After each migration, the newcomers created new understandings of the African-American experience and new definitions of blackness. Given the numbers of black immigrants arriving after 1965, and the diversity of their origins, it should be no surprise that the overarching narrative of African-American history has become a subject of contention.

That narrative, encapsulated in the title of John Hope Franklin’s classic text From Slavery to Freedom, has been reflected in everything from spirituals to sermons, from folk tales to TV docudramas. Like Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, Alex Haley’s Roots and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, it retells the nightmare of enslavement, the exhilaration of emancipation, the betrayal of Reconstruction, the ordeal of disfranchisement and segregation, and the pervasive, omnipresent discrimination, along with the heroic and ultimately triumphant struggle against second-class citizenship.

This narrative retains incalculable value. It reminds men and women that a shared past binds them together, even when distance and different circumstances and experiences create diverse interests. It also integrates black people’s history into an American story of seemingly inevitable progress. While recognizing the realities of black poverty and inequality, it nevertheless depicts the trajectory of black life moving along what Dr. King referred to as the “arc of justice,” in which exploitation and coercion yield, reluctantly but inexorably, to fairness and freedom.

Yet this story has had less direct relevance for black immigrants. Although new arrivals quickly discover the racial inequalities of American life for themselves, many—fleeing from poverty of the sort rarely experienced even by the poorest of contemporary black Americans and tyranny unknown to even the most oppressed—are quick to embrace a society that offers them opportunities unknown in their homelands. While they have subjected themselves to exploitation by working long hours for little compensation and underconsuming to save for the future (just as their native-born counterparts have done), they often ignore the connection between their own travails and those of previous generations of African-Americans. But those travails are connected, for the migrations that are currently transforming African-American life are directly connected to those that have transformed black life in the past. The trans-Atlantic passage to the tobacco and rice plantations of the coastal South, the 19th-century movement to the cotton and sugar plantations of the Southern interior, the 20th-century shift to the industrializing cities of the North and the waves of arrivals after 1965 all reflect the changing demands of global capitalism and its appetite for labor.

New circumstances, it seems, require a new narrative. But it need not—and should not—deny or contradict the slavery-to-freedom story. As the more recent arrivals add their own chapters, the themes derived from these various migrations, both forced and free, grow in significance. They allow us to see the African-American experience afresh and sharpen our awareness that African-American history is, in the end, of one piece.

Ira Berlin teaches at the University of Maryland. His 1999 study of slavery in North America, Many Thousands Gone, received the Bancroft Prize.

Adapted from The Making of African America, by Ira Berlin. © 2010. With the permission of the publisher, Viking, a member of the Penguin Group (USA) Inc.