The Closest Source We Have to Really Knowing John Wilkes Booth Is His Sister

In a post-assassination memoir, Asia Booth Clarke recalled her brother’s passion, his patriotism and his last words to her

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/68/7468676f-69c9-4404-8646-1c348615cd12/mar2015_l02_asiabooth_copy.jpg)

Asia Booth Clarke, sickly pregnant with twins at her mansion in Philadelphia, received the morning newspaper on April 15, 1865, in bed and screamed at the sight of the headlines: John Wilkes, her younger brother, was wanted for the assassination of President Lincoln.

Asia was married to an actor, John Sleeper Clarke. In their home, they kept an iron safe, where Asia’s brother often stored papers when he traveled. As the reality of Lincoln’s death took hold, Asia remembered documents that Booth had deposited during the winter and fetched them. In a large sealed envelope marked “Asia,” she found four thousand dollars’ worth of federal and city bonds; a Pennsylvania oil-land transfer, made out to another of her brothers; a letter to their mother explaining why, despite his promises, Booth had been drawn into the war; and a written statement in which he tried to justify an earlier attempt to abduct the president as a prisoner of the Confederacy.

Years later, Asia would describe these events—and attempt to explain her brother—in what is today a lesser-known memoir. Scholars have “delighted” in the slender book, says Terry Alford, a John Wilkes Booth expert in Virginia, because it remains the only manuscript of significant length that provides insightful details about Booth’s childhood and personal preferences. “There’s no other document like it,” Alford told me.

Booth’s letter to his mother did not run immediately in the press, but the manifesto did, supplying what Asia called “food to newsmongers and enemies” and drawing “a free band of male and female detectives” to her doorstep. As the manhunt proceeded, the authorities twice searched her home. Her difficult pregnancy exonerated her from having to report to Washington—a detective was assigned to her home, instead, to read her mail and coax her to talk—but her husband, a Unionist, was taken temporarily to the capital for interrogation. One of her brothers, Junius, an actor and theater manager, was also arrested—on the same day, as it happened, that the authorities finally tracked John to a barn in Virginia and shot him dead. He had been at large for 12 days.

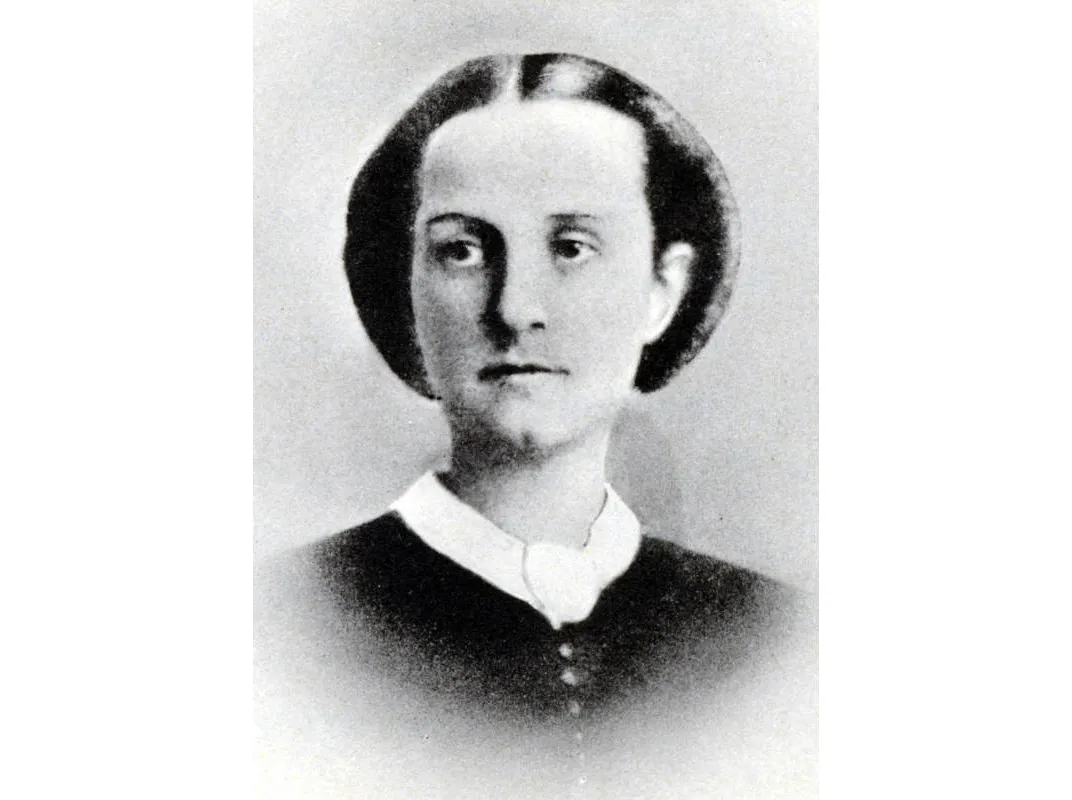

Asia was the fourth of the six Booth children who lived to adulthood; John was number five. The two were extremely close. Several years before Lincoln’s death, they had started collaborating on a biography of their famous father, a stage actor. Unable to focus, Booth had left the project to his sister. With the family name destroyed, Asia recommitted herself to the biography, which was published in 1866, and to regaining credibility.

She also became formally religious. The Booths had raised their children to be spiritual without directing them to any one church, but her brother’s ignominious act, along with his death, had “brought to a crisis Asia’s need for a sense of legitimacy and order,” Alford has noted. After converting to Roman Catholicism, Asia had her children baptized in the church. In the spring of 1868, having renounced the United States, she moved with her family to London.

In England, Asia gave birth to three more children. They all died. Her rheumatism grew worse. Friendless, she felt isolated and estranged from her husband, who was often away at the theater. Every Fourth of July, and on George Washington’s birthday, she would hang an American flag in nostalgia for the homeland to which she felt she couldn’t return. By now, she had lost her adored brother, her country, her parents, several children, her health, and now she was losing her husband to “dukelike haughtiness” and “icy indifference,” not to mention a mistress. London she despised: its weather, chauvinism, food. “I hate fat, greasy-voiced, fair-whiskered Britons with all my heart,” she wrote in a letter in 1874.

Nine years had passed since Lincoln’s death. Lonely and irritable, Asia revised the biography of her father and began writing about her brother. In distinctive, slanted handwriting, she worked quickly in a small, black-leather journal equipped with a lock. “John Wilkes was the ninth of ten children born to Junius Brutus and Mary Anne Booth,” she began.

The second paragraph sketched a haunting précis:

His mother, when he was a babe of six months old, had a vision, in answer to a fervent prayer, in which she imagined that the foreshadowing of his fate had been revealed to her....This is one of the numerous coincidences which tend to lead one to believe that human lives are swayed by the supernatural.

Asia, a poet, had made verse of the “oft-told reminiscence” of the vision, as a birthday gift for her mother 11 years before the assassination. (“Tiny, innocent white baby-hand / What force, what power is at your command / For evil, or good?”) Now, in the memoir, she also recounted an eerie experience her brother had as a boy, in the woods near the Quaker boarding school that he attended in their native Maryland: A traveling fortuneteller told him “Ah, you’ve had a bad hand....It’s full enough of sorrow. Full of trouble.” He had been “born under an unlucky star” and had a “thundering crowd of enemies”; he would “make a bad end” and “die young.”

The young Booth wrote out the fortune in pencil on a scrap of paper that eventually wore to tatters in his pocket. Asia wrote that in “the few years that summed up his life, frequent recurrence was sadly made to the rambling words of that old Gipsey in the woods of Cockeysville.”

Asia was smart and sociable, with a mind for mathematics and poetry. Her father thought she had a “sulky temper” at times. Thin and long-faced, she had narrow lips, brown eyes and a cleft chin, and wore her dark hair parted down the middle and gathered up in back.

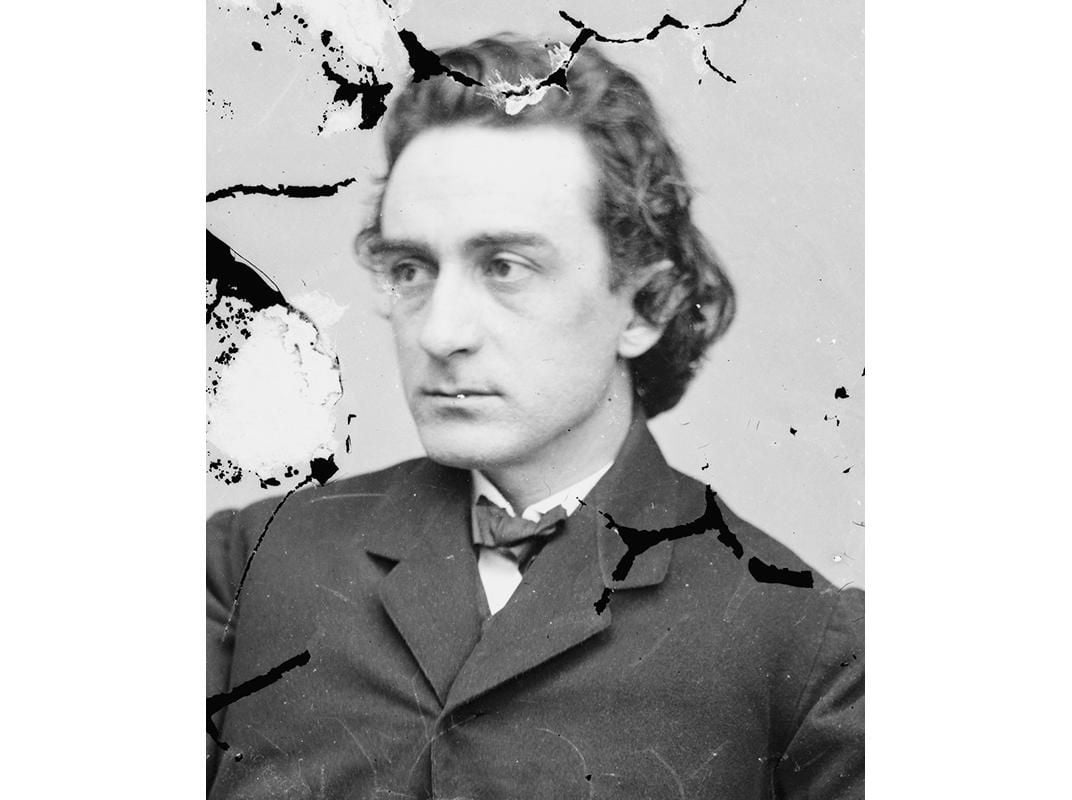

Her brother was beautiful, with “long, up-curling [eye]lashes,” “perfectly shaped hands,” his “father’s finely shaped head,” and his mother’s “black hair and large hazel eyes,” she wrote. In intimate detail, Asia documented his preferences and habits, as if to freeze his memory and humanize him before the public:

He had a “tenacious rather than an intuitive intelligence” as a boy—he learned slowly but retained knowledge indefinitely. He had a “great power of concentration”—at school, he sat with “forehead clasped by both hands, mouth firm set, as if resolute to conquer.” When trying to accomplish a difficult task, his strategy was to imagine challenges as a column of foes to be struck down one by one. In the woods, he practiced elocution. (“His voice was a beautiful organ.”) A lover of nature, he might “nibble” some roots or twigs or throw himself to the ground to inhale the “earth’s healthy breath,” which he called “burrowing.”

The president’s killer loved flowers and butterflies. Asia noted that her brother considered fireflies “bearers of sacred torches” and that he avoided harming them. She remembered him as a good listener. He was insecure about his lack of stage grace, and he worried about his chances as an actor. The music that he enjoyed tended to be sad, plaintive. A flautist, he adored reciting poetry and Julius Caesar. He loathed jokes, “particularly theatrical ones.” He smoked a pipe. He was a “fearless” rider. He preferred hardwood floors to carpet for the “smell of the oak,” and sunrises to sunsets, which were “too melancholy.”

Describing her brother’s bedroom, Asia wrote: “A huge pair of antlers held swords, pistols, daggers and a rusty old blunderbuss.” His red-covered books, cheaply bound, contained “Bulwer, Maryatt, Byron and a large Shakespeare.” He slept on “the hardest mattress and a straw pillow, for at this time of his life he adored Agesilaus, the Spartan King, and disdained luxuries.” In dire times, he “ate sparingly of bread and preserves” so as to leave more for others. He was mannerly, “for he knew the language of flowers.”

Asia wrote straightforwardly, often lyrically. (A stream “came gurgling under the fence and took its way across the road to the woods opposite, where it lost itself in tangled masses of wild-grape bowers.”) A few passages are tone deaf (her brother, she recalled, had “a certain deference and reverence towards his superiors in authority”) or objectionable: While the family did not share Wilkes’ Southern sympathies, Asia referred to African-Americans as “darkies” and immigrants as “the refuse of other countries.”

It should be noted that Asia worked almost entirely from memory as she wrote what she might have hoped would be the definitive portrait of her brother. “Everything that bore his name was given up, even the little picture of himself, hung over my babies’ beds in the nursery,” she wrote. “He had placed it there himself saying, ‘Remember me, babies, in your prayers.’”

Several months before the assassination, Booth showed up at Asia’s house, his palms callused, mysteriously, from “nights of rowing.” His thigh-high boots contained pistol holsters. His threadbare hat and coat “were not evidence of recklessness but of care for others, self-denial,” Asia wrote. Their brother Junius would later describe to Asia a moment, in Washington, when Booth faced the direction of the fallen city of Richmond, and “brokenly” said, “Virginia—Virginia.”

During his visit with Asia, he often slept in his boots on a downstairs sofa. “Strange men called at late hours, some whose voices I knew, but who would not answer to their names,” Asia wrote, adding, “They never came farther than the inner sill, and spoke in whispers.”

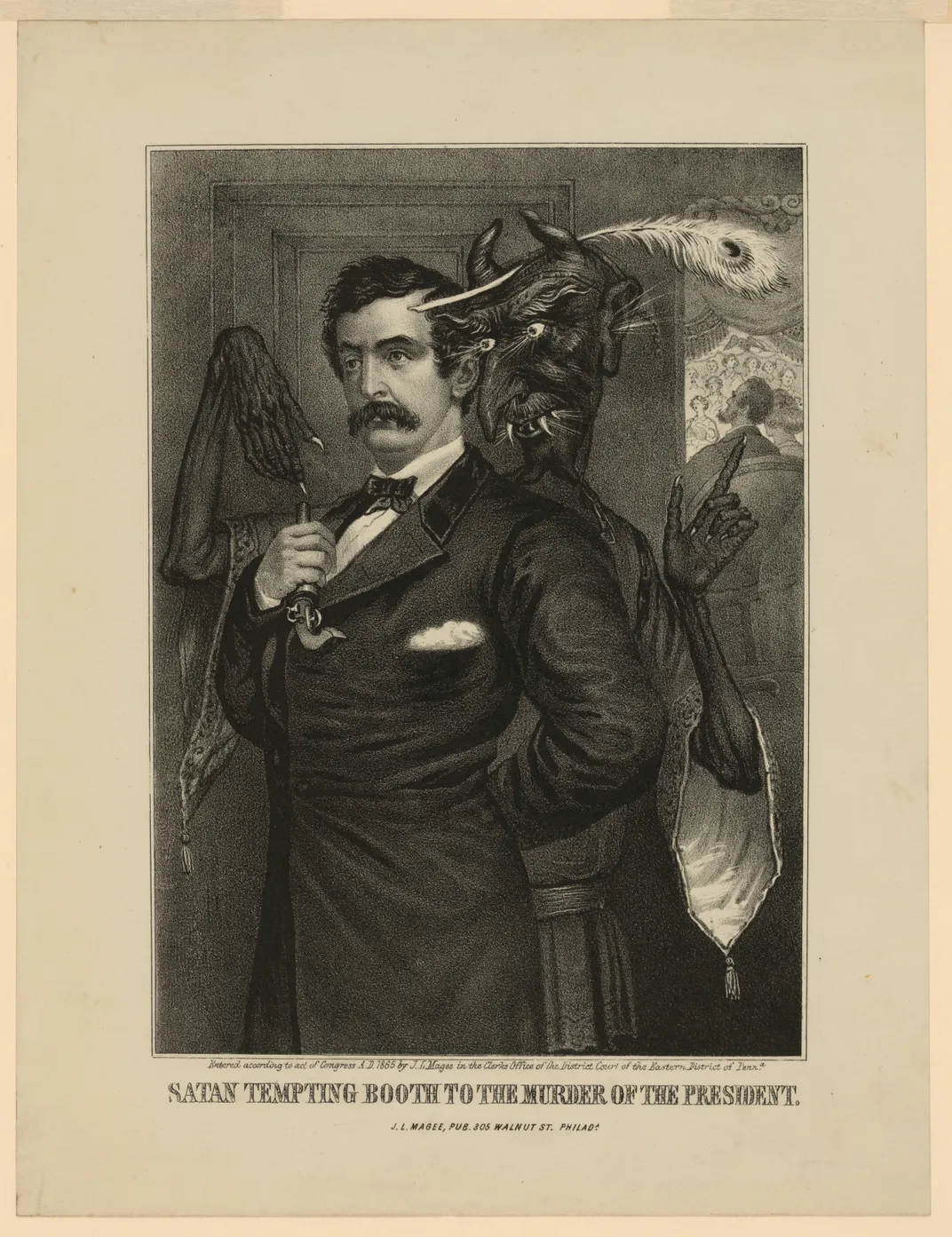

One night, Booth raged against Lincoln and his delusions about an impending monarchy. “A desperate turn towards the evil had come!” Asia wrote. For once, she found herself unable to calm her brother’s “wild tirades, which were the very fever of his distracted brain and tortured heart.”

Before having his sister deposit some of his papers in her safe, Booth told her that if anything should happen to him she should follow the instructions in the documents. He then knelt at her knee and put his head in her lap, and she stroked his hair for a while. Rising to leave, he told her to take care. She said she would not be happy until they saw each other again. “Try to be happy” were his last words to her.

“There is no more to add,” she wrote. “The rest is horror, fitter for a diary than for these pages.”

In a letter, her brother Edwin advised her to forget John: “Think no more of him as your brother; he is dead to us now, as he soon must be to all the world.”

But Asia could not let it go. She used her memoir to assert that her brother never openly plotted against the president and, contrary to rumor, never carried in his pocket a bullet meant for Lincoln. She repeatedly defended his mental health, citing the fortuneteller’s augury to explain his actions: only a “desperate fate” could have impelled someone with such “peaceful domestic qualities” to murder the nation’s leader.

Ultimately, she conceded a possibility:

The fall of Richmond “breathed air afresh upon the fire which consumed him.” Lincoln’s visit to the theater signaled the “fall of the Republic, a dynasty of kings.” His attending a play “had no pity in it,” Asia wrote. “It was jubilation over fields of unburied dead, over miles of desolated homes.” She ended her book by calling her brother America’s first martyr.

The handwritten manuscript totaled a slim 132 pages. Asia left it untitled—the cover held only “J.W.B.” in hand-tooled gold. In it, she referred to her brother as “Wilkes,” to avoid reader confusion about the other John in her life. She hoped the book would be published in her lifetime, but she died in May of 1888 (age 52; heart problems) without ever seeing it in print.

In a last wish, she asked that the manuscript be given to B.L. Farjeon, an English writer whom she respected and whose family considered Asia “a sad and noble woman,” his daughter Eleanor wrote. Farjeon received the manuscript in a black tin box; he found the work to be significant but believed the Booths, and the public, to be unready for such a gentle portrait of the president’s killer.

Fifty years passed. Eleanor Farjeon pursued publication. In 1938, G.P. Putnam’s Sons put out the memoir as The Unlocked Book: A Memoir of John Wilkes Booth by His Sister Asia Booth Clarke, with a price of $2.50. In the introduction, Farjeon described the project as Asia’s attempt to repudiate the “shadowy shape evoked by the name John Wilkes Booth.” The New York Times gave it a matter-of-fact review. In the Saturday Review, the historian Allan Nevins said it had been “written with a tortured pen.”

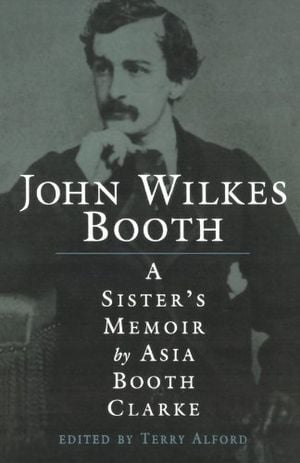

University Press of Mississippi republished the memoir in 1996 as John Wilkes Booth: A Sister’s Memoir, with an introduction by Alford, a professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College (and the author of “The Psychic Connection” on p. 40). An addendum contains family letters and documents; if Asia’s feelings about her brother are conflicted, Booth’s are made clear on the issues of slavery (a “blessing”), abolitionists (“traitors”) and secession (he was “insane” for it).

The original manuscript is privately owned, in England, according to Alford, whose research and introduction provide much of the contextual narrative detail given here. He thinks of Asia’s work as “diligent and loving,” and told me, “It’s the only thing we’ve really got about Booth. If you think about the sources, most are about the conspiracy. There’s nothing about him as a person, no context.”

Though an important commentary on Booth’s life, the text was unpolished and never “properly vetted for the reader by literary friends and a vigilant publisher,” Alford notes. Better to think of the memoir as “an intense and intimate conversation,” he wrote, “thrown out unrefined from a sister’s heart.”