The Confusing and At-Times Counterproductive 1980s Response to the AIDS Epidemic

A new exhibit looks at the posters sent out by non-profits and the government in response to the spread of AIDS

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/aa/66aa5e5a-e7fb-4498-8bcb-173a332fed91/past-imperfect-aids.jpg)

In 1981, an unknown epidemic was spreading across America. In June of that year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's newsletter mentioned five cases of a strange pneumonia in Los Angeles. By July, 40 cases of a rare skin cancer were reported by doctors working in the gay communities of New York and San Francisco. By August, the Associated Press reported that two rare diseases, the skin cancer Kaposi's sarcoma and pneumocystis, a form of pneumonia caused by a parasitic organism, had infected over 100 gay men in America, killing over half of them. At the end of 1981, 121 men had died from the strange disease; in 1982, the disease was given a name; by 1984, two different scientists had isolated the virus causing it; in 1986, that virus was named HIV. By the end of the decade, in 1989, 27,408 people died from AIDS.

In the years following the AIDS epidemic, medical research has given us a better understanding of HIV and AIDS, as well as made some remarkable breakthroughs unimagined in the 1980s: today, people living with HIV aren’t condemned to a death sentence, but rather have treatment options available. Still, to think of the AIDS epidemic in medical terms misses half of the story--the social aspect, which affected America's perception of HIV and AIDS just as much, if not more than medical research.

The two sides of the story are told through a collection of articles, pictures, posters and pamphlets in Surviving and Thriving: AIDS, Politics and Culture, a traveling exhibit and online adaptation curated by the National Library of Medicine that explores the rise of AIDS in the early 1980s, as well as the medical and social responses to the disease since. The human reaction to the AIDS epidemic often takes a back seat to the medical narrative, but the curators of Surviving and Thriving were careful to make sure that this did not happen--through a series of digital panels, as well as a digital gallery, readers can explore how the government and other community groups talked about the disease.

At the beginning of the epidemic, response was largely limited to the communities which were most affected, especially the gay male community. “People with AIDS are really a driving force in responding to the epidemic and seeing how change is made,” says Jennifer Brier, a historian of politics and sexuality who curated the exhibit.

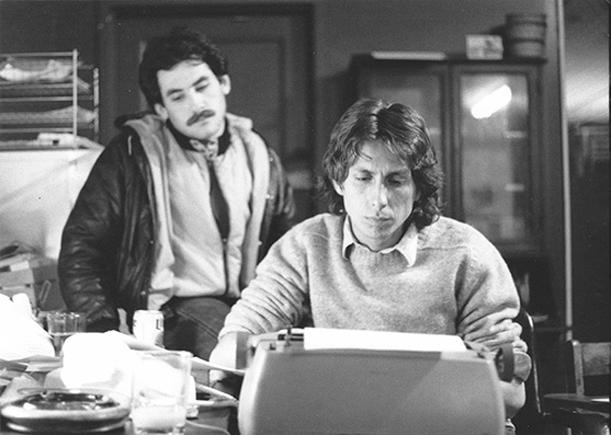

Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz, two gay men living with AIDS, wrote How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, which introduced the idea of safe sex in 1982. Image courtesy of Richard Dworkin.

In 1982, Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz, two gay men living with AIDS in New York City, published How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, which helped spread the idea that safe sex could be used as protection against spreading the epidemic--an idea that hadn't yet become prevalent in the medical community. The pamphlet was one of the first places that proposed that men should use condoms when having sex with other men as a protection against AIDS.

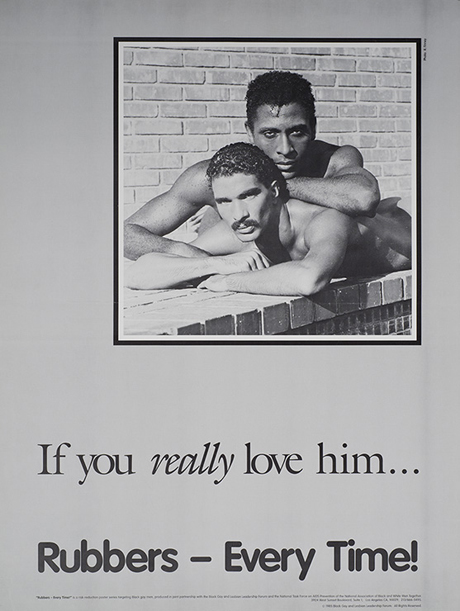

Condoms as protection against AIDS became a major theme for poster campaigns. The above poster, paid for by the Baltimore-based non-profit Health Education Resource Organization, shows how visuals attempted to appeal, at least at first, to the gay community. Due to widespread misinformation, however, many people believed that AIDS was a disease that affected only white gay communities. As a response to this, black gay and lesbian communities created posters like the one below, to show that AIDS didn't discriminate based on race.

Poster from the Black Gay and Lesbian Leadership Forum, in Los Angeles, 1985. Photo courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Many posters and education campaigns harnessed sexual imagery to convey the importance of safe sex in an attempt to make safety sexy (like the Safe Sex is Hot Sex campaign), but it wasn't a campaign tactic supported by governmental bodies--in fact, in 1987, Congress explicitly banned the use of federal funds for AIDS prevention and education campaigns that "[promoted] or [encouraged], directly or indirectly, homosexual activities" (the legislation was spearheaded by conservative senator Jesse Helms and signed into law by President Reagan).

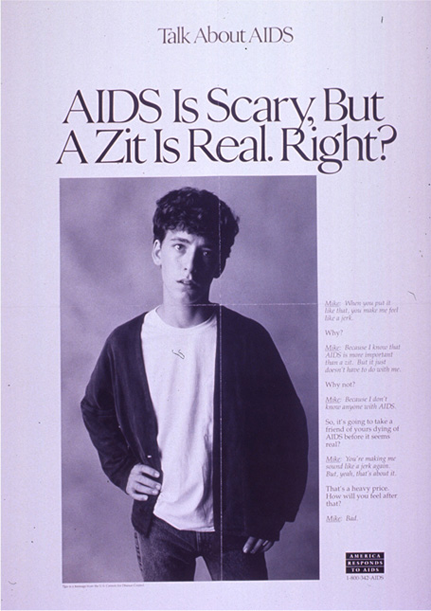

Instead, federally-funded campaigns sought to address a large number of people from all backgrounds--male, female, homosexual or heterosexual. The America Responds to AIDS campaign, created by the CDC, ran from 1987 to 1996 and became a central part of the "everyone is at risk" message of AIDS prevention.

This poster spoke to parents about the challenges of talking to a teenager about AIDS, but stressed that the issue was relevant and important to young Americans. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

The campaign was met with mixed feelings by AIDS workers. "The posters really do help ameliorate the fear of hatred of people with AIDS," Brier explains. "There’s a notion that everyone is at risk, and that’s important to talk about, but there’s also the reality that not everyone is at risk to the same extent." Some AIDS organizations, especially those providing service to communities at the highest risk for contracting HIV, saw the campaign as diverting money and attention away from the communities that needed it the most--leaving gay and minority communities to compete with one another for the little money that remained. As New York Times reporter Jayson Blair wrote in 2001 (, "Much of the government's $600 million AIDS-prevention budget was used...to combat the disease among college students, heterosexual women and others who faced a relatively low risk of contracting the disease."

(This linked column by Blair was later found to be plagiarized from reporting by the Wall Street Journal, but the point still holds.)

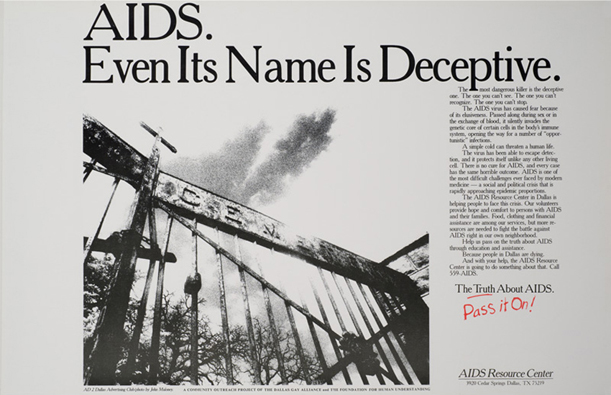

Beyond campaigns that tried to generalize the AIDS epidemic, a different side used the fear of AIDS to try and affect change. These posters, contained under the section "Fear Mongering" in the exhibit's digital gallery, show ominous images of graves or caskets behind proclamations of danger.

"It was like this sort of scared straight model, like if you get scared enough, you really will do what is right," Brier says of the posters. "There were posters that focused on pleasure, or health, or positive things to get people to affect change in their behavior, but there were consistently posters that used the idea that fear could produce behavior change."

"A bad reputation isn't all you can get from sleeping around." Poster courtesy of Dallas County Health Department.

The above poster exemplifies the tactic of fear mongering: a large, visible slogan to affect fear (and shame sexual behavior), while information on how to prevent the spread of AIDS is buried in small print at the bottom of the poster. A lack of information was typical of fear-mongering posters, which relied on catchy, scary headlines rather than information about safe sex, clean needles or the disease itself.

"The posters fed on people’s inability to understand how AIDS actually spread. It didn’t really ever mention ways to prevent the spread of HIV," Brier says. "Fear-mongering posters don’t talk about condoms, they don’t talk about clean needles, they don’t talk about ways to be healthy. They don’t have the solutions in them, they just have the fear."

This ominous image claims that "people are dying to know" facts about AIDS. Poster from the Pharmacists Planning Service.

Through exploring the exhibit, users get a sense of the different approaches public organizations took to spread information about AIDS. "It's a fundamental question of public health," says Brier. "Do you spread information by scaring people, do you do it by trying to tap into pleasure or do you do it by recognizing that people’s behavior isn’t just about their individual will but a whole different set of circumstances?"

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)