The Desperate Would-be Housewife of New York

Not even a murder trial and the unmasking of her fake pregnancy stopped Emma Cunningham’s search for love and legitimacy

![]()

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1857

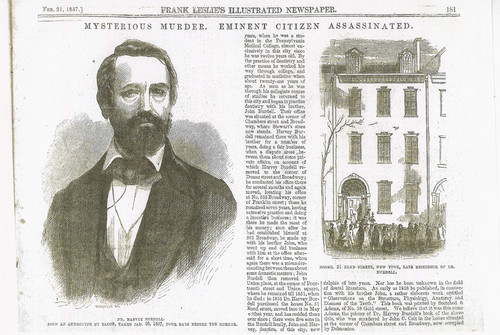

In the early evening of January 30, 1857, a middle-aged dentist named Harvey Burdell left his townhouse at 31 Bond Street, a respectable if not truly chic section of Manhattan, and set out for a local hotel. Burdell had recently been taking his dinners there, even though he had a cook on his household staff. His relationship with one of his tenants (and a regular at his table), Emma Cunningham, had become strained. Burdell had accused Cunningham, a 34-year-old widow with four children, of stealing a promissory note from his office safe. She in turn had had Burdell arrested for breach of promise to marry, which was then a criminal offense.

Cunningham had become increasingly suspicious of Burdell’s relations with his female patients and with his attractive young cousin, also a resident of 31 Bond Street. Earlier that day, she had grilled one of the housemaids:

“Who was that woman, Hannah, you were showing through the house to-day?”

“That was the lady who is going to take the house.”

“Then the doctor is going to leave it, is he?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“And when does she take possession?”

“The first of May.”

“He better be careful; he may not live to sign the papers!”

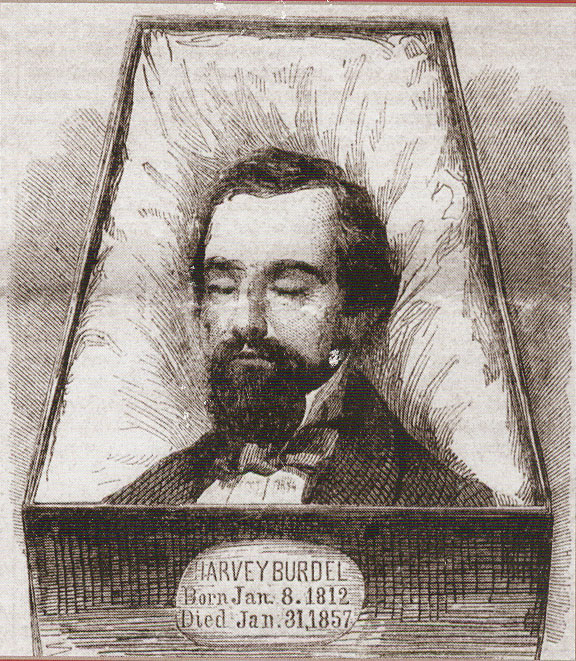

This conversation, which Hannah repeated to police and in a courtroom, would come back to haunt Emma Cunningham. On the morning of January 31, Harvey Burdell was found in his home, stabbed 15 times and strangled for good measure.

She was born Emma Augusta Hempstead in the mid-1810s in Brooklyn. When she was 19, she met and married George Cunningham, a businessman some 20 years her senior, and the two lived in relative style in a rented house near Union Square in Manhattan. But he proved to be less than adept at handling money, and by the time their fourth child was born they had moved back to Brooklyn to live among relatives. When he died, Emma Cunningham inherited his property (meager), accounts (empty) and a life-insurance policy worth $10,000. She knew that wouldn’t be enough to support her family indefinitely, especially not if she wanted to move back to Manhattan and live as a proper lady.

Using a portion of the money to outfit herself in the latest fashions, the widow Cunningham set about finding a new husband—one who would ensure that she and her children could remain among the ranks of New York’s upwardly mobile middle class. At that time, love, legitimacy and security were difficult to come by for any woman not born into privilege. Emma Cunningham’s search would prove to be more desperate than most.

How and where her path crossed Harvey Burdell’s is unclear, but in the summer of 1855 the pair jaunted to the resort of Saratoga Springs to promenade. By that autumn Cunningham was pregnant and expecting a proposal of marriage; she instead had an abortion, almost certainly at Burdell’s urging, and possibly performed by the dentist himself. She moved her children into 31 Bond Street not as lady of the house but as a tenant, paying rent to Burdell.

Still, she behaved as though she and Burdell were man and wife—ordering the food, hiring the maids, dining at his table. The breach-of-promise suit, brought in 1856, was a final attempt to get Burdell to legitimize their relationship, which Cunningham had become increasingly anxious to do as she noticed the attentions he paid to other women. The two fought constantly, with neighbors reporting later that shouts and crashes came from 31 Bond almost nightly. Burdell refused her demands for marriage, telling a friend that he would not marry “the best woman living.”

Harpers, 1857

Found among Burdell’s papers after his death was a document that read:

In consequence of the settling of the suit now pending between Emma Augusta Cunningham and myself I agree as follows:

1.1 I extend to herself and family my friendship through life.

1.2 I agree never to do or act in any manner to the disadvantage of Mrs. Emma A. Cunningham.

Harvey Burdell

His associates took this declaration to mean that he and Cunningham had reached some kind of agreement, and so were shocked to learn that Cunningham, two days after Burdell’s body was discovered, presented to the coroner’s office a marriage certificate. Not only was she Burdell’s grieving widow, devastated by his death and horrified that anyone could have such animosity toward her beloved, she announced, she was also the sole heir of his $100,000 fortune and the Bond Street townhouse. She was soon indicted on charges of murdering him.

The press painted Cunningham as a money-hungry schemer. She was sleeping with at least one of the other boarders, it was alleged, and allowing one of her lovers to engage in immoral acts with her 18-year-old daughter. Household staff and neighbors came forward with stories of lurid sexual escapades and elaborate plots to ruin the good name of the dentist who had worked so hard to rise to the ranks of the professional class.

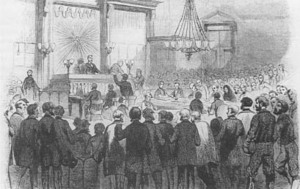

At her trial, the prosecution relied on physical evidence: The murderer was almost certainly left-handed; Emma Cunningham was left-handed. What more was there to debate?

Cunningham’s attorney, Henry Clinton Lauren Clinton, pointed out that while his client (whom he discouraged from taking the witness stand) did indeed lead with her left hand, so did who knows how many others across the city. What’s more, he said, Cunningham, by this point in her mid-30s, was an aging woman suffering from rheumatism. Burdell had 12 inches of height and a hundred pounds on her—even if she’d wanted to, how could such a delicate creature commit such a physically demanding act?

Clinton’s portrait of Burdell and his relationship with Cunningham was much darker than the initial press accounts. It was confirmed that Burdell had been engaged once before and, on the day of the wedding, demanded a check for $20,000 from the bride’s father, whereupon the marriage was called off. He regularly engaged in sexual activity with his dental patients, preferring girls in their late teens. He owed gambling debts and was parsimonious to the point of cruelty, almost starving his servants. He’d been especially abusive, the defense claimed, to Mrs. Cunningham. Court papers alluded to a variety of sexual assaults, verbal abuse and humiliation. The abortion she’d been convinced to undergo in the fall of 1855 was not her last—several others had occurred in the dentist’s chair. One newspaper claimed to have obtained, from a secret cabinet in Burdell’s office, a jarred fetus—a result of Cunningham and Burdell’s relations.

Whether persuaded by Clinton’s presentation or the fact that there was no physical evidence linking Cunningham to the murder, the jury acquitted her in less than two hours. The wicked woman, the press exclaimed, had gotten away with murder.

There was still, though, the matter of Cunningham’s marriage to Burdell. More than one member of Burdell’s inner circle had challenged the marriage certificate as a fake, and the Surrogate Court was investigating Cunningham’s activities in the months leading up to the murder trial.

Harpers, 1857

Not believing her assertion that Burdell had sworn her to keep their marriage a secret, especially from his own attorneys, court-appointed State’s Attorney Samuel J. Tilden (future governor of New York and presidential candidate, who was representing the Burdell family) presented to the court a seemingly outlandish scenario: Cunningham was having an affair with another of Burdell’s tenants, John J. Eckel; she had hired a minister who knew neither Eckel nor Burdell and disguised Eckel in a fake beard to match Burdell’s real one, and then she had married Eckel, who forged Burdell’s signature on the marriage certificate. The press took the idea to its logical conclusion: Eckel and Cunningham, drunk on lust and greed, had conspired to murder Burdell and live together ever after on the dead dentist’s dime. (Eckel was never charged with murder, but his case was dismissed.)

Cunningham’s every move was publicly scrutinized—the New-York Daily Times spoke to neighbors who claimed she “constantly had several women in her house; that she would sit in the front parlor, in company with one or more of them, with the blinds and windows open; and thus exposed to the gaze of the over-curious public, would talk to them in the most violent and boisterous manner, gesticulating and preforming various fantastic feats, laughing in triumph, shaking her fist, &c.”

Men of all ages were reported to be entering the house at all hours of the night. Anyone living in New York at the time would have caught the insinuation—the area around Bond Street, being next to some of the city’s most notorious theaters, was widely recognized as a center of prostitution. While there is no evidence Cunningham ever engaged in prostitution, the newspaper coverage had inclined the obsessed public to believe she was that kind of woman.

With a Surrogate Court decision expected in late August, eyebrows were raised as Cunningham began to appear in court looking noticeably fuller around her midsection. Yes, she said, she was pregnant with her late husband’s child. No, she demurred, she would not submit to an examination by any physician but her own.

From her initial pregnancy announcement, whispers grew to the effect that Cunningham was padding her gowns with pillows and faking exhaustion and other symptoms of the condition. In early August, she appeared in public with an infant, hoping to silence the rumors that she’d been anything other than a devoted wife and mother.

Alas, it was not to be, and Cunningham found herself once more in the Tombs and on the front page of every newspaper in the city. While she swore the baby was the product of her marriage to Burdell, she had in fact purchased the baby for $1,000 from an indigent woman, in a plot engineered by District Attorney Abraham Oakley Hall, who had been skeptical of her pregnancy from the start. The would-be mother went so far as to stage a birth scene at her home: “About half past ten o’clock both physicians entered, and in due form Mrs. Cunningham was ‘brought to bed,’ ” reported the New-York Daily Times. “A fictitious afterbirth had been prepared, and a large pailful of lamb’s blood. The bloody sheets of Mrs. Cunningham’s bed and the placenta, stowed away in a cupboard, completed this mock confinement, which had also been systematically accompanied with imaginary pains of labor.”

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1857

After Cunningham presented the baby as her own, Hall produced the baby’s mother, and noted a series of small marks that had been made on the infant in the foundling hospital where it had been born. With that, Cunningham’s quest to get what she thought Harvey Burdell owed her was finally put to rest, though baby’s mother did find a way to capitalize on the situation—cutting a deal with showman P.T. Barnum to exhibit the child at his downtown Manhattan museum, where visitors could pay 25 cents a head to gaze upon the infamous infant.

Disgraced and virtually penniless, Cunningham fled to California—where she eventually wed and placed her daughters in respectable marriages. She returned to New York in 1887 to live with a cousin but died that year, an event marked by a small notice in the New York Times. The murder of Harvey Burdell was never officially solved, though modern scholars agree Cunningham was likely involved.

What she wanted from Harvey Burdell was not just his wealth, but also his attention. And in a small way, she has it—in 2007 Benjamin Feldman, a lawyer and historian researching the case, partnered with persuaded Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn to erect two stone markers, one for Cunningham and one for Burdell, to stand side by side for eternity, just as Cunningham, throwing herself onto Burdell’s coffin before at his packed funeral, exclaimed she wanted.

That she got it wouldn’t have come as a surprise to Harvey Burdell. One of his last conversations about Cunningham was with a cousin, who recounted it on the witness stand:

Q: Did he speak very highly of her?

A: Yes.

Q: Did he tell you that she was a rich widow?

A: Yes. He said she was lady-like. He said that to have a public outbreak with her, he feared, would injure his business; he said she was a cunning, intriguing woman, and that she would resort to anything to carry out her plans.

Sources

Books: Clinton, Henry Lauren. Celebrated Trials (Harper & brothers, 1897); Feldman, Benjamin. Butchery on Bond Street: Sexual Politics and the Burdell-Cunningham Case in Ante-bellum New York (Green-wood Cemetery Historic Fund, 2007); Sutton, Charles. The New-York Tombs: Its Secrets and Mysteries (A. Roman & Company, 1874)

Articles: “The Bond Street Murder: Indictment of Eckel and Mrs. Cunningham,” New-York Daily Tribune, February 23, 1857; “The Widow Burdell Before the Surrogate,” New York Daily Times, March 13, 1857; “Mrs. Cunningham: Is the House Haunted,” New York Daily Times, August 8, 1857; “The Burdell Murder!!: The Burdell Estate Before the Surrogate Again,” New York Daily Times, August 5, 1857; “The Burdell Murder: Scenes in Court. Eckel Discharged,” New York Daily Tribune, May 11, 1857; “A Lurid Tale Revived in Granite,” New York Times, September 19, 2007.