Sometime in the spring of 1893, Cassie Kirby Smith contacted Alexander Darnes, one of Florida’s first formally trained Black doctors. She shared news of a memorial honoring her recently deceased husband, Edmund Kirby Smith, a former Confederate general and professor at the University of the South.

Though Cassie’s original communication has not survived, Darnes’ reply has, and it suggests that someone made a special request: Might he be so kind to share a few words, destined for a Confederate veterans’ publication, about Cassie’s dear spouse?

Darnes agreed, and in a self-described “humble attempt” that ran almost 20 handwritten pages, Darnes extolled the virtues of the man, who was among the last Southern generals to surrender—more than a month after Robert E. Lee negotiated the end of the Civil War.

“He was a generous, virtuous Christian gentleman … a brave soldier with a benevolent turn of mind and heart of a nobleman,” Darnes wrote. “I had a good opportunity to see and know much of this good and most excellent gentleman in his private as well as in his public life. I speak truthfully when I say he was no slave to any habit whatever that was not good”—not drinking, gambling, swearing or other raucous behaviors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/fd/c0fdc758-994e-4643-847d-516a33d7d428/janfeb2023_c06_confederate.jpg)

That was high praise indeed, for Darnes had accompanied Kirby Smith across the country and beyond as his enslaved manservant. They’d been stationed at Jalapa and Veracruz during the Mexican-American War, and when that conflict ended, they headed to West Point, where the bespectacled and studious Kirby Smith taught math to soldiers. Darnes and Kirby Smith then traveled the West together during campaigns against Native peoples resisting American encroachment. And eventually, as he recounted in his long letter, Darnes was nearby when Kirby Smith took a shot in the shoulder at the First Battle of Bull Run, near Manassas, Virginia.

Privilege tends to create archives. Anyone today who wants to learn more about Kirby Smith can go to the University of North Carolina, where his archival collection contains more than 2,000 personal and family items spanning from 1776 to 1906—everything from diaries to stock certificates. His military travels; his administration of the sprawling Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department (which included parts of Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Texas and points west in then-Indian Territory); and his geographically sprawling family meant that his letters landed in archives far and wide. His camp trunk, a traveling footlocker, now rests in the Smithsonian. Thousands of preserved plant samples he collected reside in a University of Florida museum. In the 1950s, Kirby Smith was the subject of an award-winning biography. Until recently, there was a Kirby Smith Middle School in Florida and a Kirby Smith dormitory at Louisiana State University. The Jacksonville “camp” of the Sons of Confederate Veterans still bears his name, as does a chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy in Tennessee. Famously, a statue of Kirby Smith was installed in the National Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol in 1922, where it remained until it was replaced in 2022 by a statue honoring the African American educator Mary McLeod Bethune. The sculptor of the Kirby Smith likeness, a fellow Floridian, was able to use one of the general’s actual army coats to size him up. Occasionally, eBay vendors still sell Christmas tree ornaments, pillow shams and T-shirts with Kirby Smith’s image.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ec/6e/ec6e4d2a-a559-462f-8009-5bf03805820b/triptych.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/a6/bca62330-7b62-4c77-a786-369ed2271b6f/janfeb2023_c09_confederate.jpg)

Darnes’ testimony stands apart from the rest of Kirby Smith’s legacy. It’s an astounding historical document. Because teaching slaves to read or write was prohibited in many states and cities, missives written by former or then-current bondspeople are exceedingly rare. Even UNC’s Southern Historical Collection, which contains 20 million manuscripts and houses most of Edmund Kirby Smith’s papers, has only about 60 letters confirmed to have been written by enslaved people. That’s considered an abundance for an archive. Rarer still are such accounts recalling the Confederate sidelines of the Civil War.

Darnes’ letter has inspired a growing circle of history buffs and professionals to hunt high and low for any archival trace of him. Confederate heritage groups, artists, an archivist, a community historian and Darnes’ modern-day family all claim him as a hero. After emancipation, Darnes became a physician who treated his neighbors, white and Black alike, during devastating epidemics in Jacksonville. He was also a founding father of a still-extant African American Masonic lodge, and a leading member of a small but influential Black elite in Jacksonville.

To some, he was a self-made man, that much-romanticized American archetype, who carefully navigated the fraught transition from slavery to success as a free man and physician. But even his admirers concede, uncomfortably, that the letter could be interpreted as the writing of a faithful slave whose fidelity outlasted slavery itself and one whose freedom-times letter seemed to minimize slavery’s innate brutality. It wasn’t entirely unusual for some formerly enslaved people to speak favorably of the people who once owned them—especially those known as “good” masters, a subjective label that often referred to those who didn’t overwork slaves, frequently and brutally punish them, or separate them from their families.

Darnes’ letter further distinguished him. He had achieved literacy and clout, and he was a person who extended extreme magnanimity to the man and family that kept him in proverbial chains. The Kirby Smith family knew where to find Darnes by mail, but the doctor and the general did not seem to correspond or meet regularly. Upon hearing of Kirby Smith’s death, Darnes expressed deep regret that he hadn’t accepted multiple invitations to visit, though he was always gratified when the general looked him up wherever he resided. At some point, Darnes acquired a cardboard-mounted photograph of the aged and hoary Kirby Smith, signed “with the esteem and affectionate regards of your old master and friend.”

All in all, what we know about the relationship between Darnes and his former master doesn’t fit neatly into modern assumptions about how formerly enslaved people felt about those who owned them. Darnes’ eulogizing letter likely won’t ever circulate on the internet like the August 1865 letter of Jourdon Anderson, which has become social media legend. Months after the end of the Civil War, Anderson, living in Ohio, answered a missive from his former master who’d asked him to return to work on the Tennessee farm he’d left after emancipation. Anderson didn’t mince words: He asked whether he and his wife would be paid back wages, since they’d labored for free for 30 years—a stint that he reckoned was worth more than $11,000. Darnes’ letter provides no such satisfaction for the contemporary reader who wants indisputable evidence of slavery’s harm.

But there is no single story about slavery. The archival breadcrumbs of Darnes’ life in bondage show that slavery was a series of forced intimacies—daily acts of domination and negotiation. Darnes was Kirby Smith’s only company from home during military campaigns. As a child living with Kirby Smith in remote and sometimes dangerous military outposts, he had to depend on his enslaver for his daily bread and shelter. Over the decades of Darnes’ captivity, Kirby Smith also depended on him to care for his wardrobe, his weapons, his papers, his very person. Due to the coercive institution that bound them but dispossessed one of them, Darnes and Kirby Smith were responsible for each other.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/ef/31efe5c2-5470-4623-a393-f28068a433fa/janfeb2023_c17_confederate.jpg)

The Black population of St. Augustine, Florida, dates to 1565. Those early Black residents were joined by runaways from the Carolina colony—the Spanish accepted fugitives and promised not to return them to their erstwhile owners. By the late 1730s, a governor had granted Black residents their own town, Fort Mose, in St. Augustine, in exchange for loyalty, military alliance against the British, and conversion to Catholicism.

That freedom held for only so long. The Spanish lost the colony to the British in 1763, and many of the colony’s Black residents fled to Cuba, fearing British retaliation. The British interregnum lasted 20 years until the Spanish reclaimed the territory. In 1821, Florida became part of the United States, and it was admitted to the union in 1845 as a slave state.

The 1850 U.S. census listed four enslaved people belonging to Edmund Kirby Smith’s widowed mother, Frances Kirby Smith, on Aviles Street in St. Augustine: a 4-year-old girl, a 50-year-old woman, a 26-year-old woman and a 10-year-old mulatto boy. The last of these was probably Darnes, who was known by the family as Aleck or Alex. Some sources suggest that his mother, Violet Pinckney, gave birth to him at age 16.

Young Aleck Darnes left St. Augustine in 1847, when he joined Edmund Kirby Smith in Jalapa, Mexico, a hot spot in the Mexican-American War. It would appear that Darnes had long been intended to serve the young officer. In 1845, while Kirby Smith was a cadet at West Point, his father, Joseph Smith, sent him a letter: “Your servant boy Alex thrives rapidly and will be a useful waiter for you in a year or so—when you graduate.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0b/9e/0b9ee662-e7bf-41ed-970c-3fd4d1b0c95a/janfeb2023_c08_confederate.jpg)

Walt Bachman, a writer who studies the use of slaves in military settings, found dozens of vouchers that Kirby Smith submitted for provisions he bought for his “servant.” As Bachman explained to me, “The Army had a unique pay system that boosted an officer’s pay if he kept a servant. The Army’s system created a great incentive for officers to obtain an enslaved servant who could be taken wherever the officer or surgeon was sent.” He added, “Obviously, a slave could not refuse to join any master, even if he or she knew the risks of being sent to a war zone.”

Sometimes those slaves were children. Darnes was in the Mexican-American War theater when he was probably no more than 7 or 8 years old. Kirby Smith received reimbursement for Darnes from 1847 to 1861—right up to the Civil War, when Kirby Smith resigned from the U.S. Army to take up arms for the Confederacy.

This was not the usual forced separation of the enslaved family. Kirby Smith’s letters to his mother, Frances, occasionally included a line or two about Darnes. In a letter dated August 15, 1859, Kirby Smith told Frances that the boy was growing “prodigious in stature and laziness. He is as slow as he is long-legged.” Three weeks later: “I enclose you my dear mother a letter of Aleck for his mother … Send me her address for Aleck’s benefit.”

Along with nostalgic references to the old house on Aviles, those letters also included discussions of possible slave sales. Though the Kirby Smith family didn’t live far from the outdoor pavilion in St. Augustine where people were sometimes auctioned off, the people they enslaved moved in and out of the household in less public ways. In November 1859, Edmund wrote from Fort Cooper, Texas, “I am glad that Kate expects to purchase Violet.” The purchaser was relative Kate Kirby Putnam Calhoun, daughter-in-law of the vociferously pro-slavery politician John C. Calhoun, and Violet was Darnes’ mother, Violet Pinckney. Kirby Smith added, “I will in all probability be an old bachelor and able to support all the old family negroes if necessary.” He further instructed that his nanny, Peg, should never be sold unless he personally approved the purchase. In a letter back to her son, Frances reported ominously that Violet was “much changed” and “saddened” into being a “staid, faithful servant” after discipline in the Calhoun household. She remarked on Aleck, opining that “the poor boy” had not been blessed with brilliance, but noted, “he is attached to you.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/86/fa/86fa9469-0341-4cab-b91a-24becd6f4412/janfeb2023_c01_confederate.jpg)

Kirby Smith and Cassie Selden, a spirited demoiselle from Lynchburg, Virginia, married in 1861. She’d caught his eye by winning an informal contest to sew a coarse blue-and-white-dotted flannel shirt for the young colonel, who was in the city preparing for war. Cassie won her man by having one of her enslaved people—predictably, “Mammy,” the household manager—craft perfect buttonholes. (“I’ve always been glad I told the lie,” she added.)

Darnes spent time with the couple as they prepared for war and separation. Cassie Kirby Smith described that time in a chatty booklet designed for her grandchildren, “All’s Fair in Love and War, or the Story of How a Virginia Belle Won a Confederate General.” She felt tension with the boy, whom she said wept when he heard Kirby Smith would marry in a troubled time and asked, “Don’t I serve you and take care of you always?” Whenever she helped her husband put on his coat, she wrote, “Aleck always stood by looking at me with jealous eyes, feeling that I had usurped his privileges.” She once kvetched to her husband that she could no longer stand the young man’s supposed impertinence, evidenced by the fact he saluted her rather than saying “Yes, ma’am” when receiving orders.

As historian Thavolia Glymph has written in Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household, the household was a “workplace and … a field of power relations and political practices”—and a milieu where violence perpetually loomed. Despite her subordination to her husband or whatever patriarch ruled in her home, the mistress was capable of wielding tremendous power: meting out violence herself; encouraging slave sales; delegating beatings to overseers and male proxies; or suggesting, as Cassie did, that some discipline was in order. For many enslaved people, a mistress’s complaint of impudence could end in a beating. But Edmund laughed it off and told his wife the response was simply Darnes’ “military training.”

Darnes appears in various roles in Cassie’s writing: rival, waiter, guard, advance scout who made travel and other arrangements for the young couple, her husband’s biggest hype man, trusted servant, collaborator and competitor. Cassie’s account and Darnes’ letter agree on most major points and events. Yet her memoir raises a glaring question that’s probably an inaccuracy. Cassie asserted that her late husband “did not believe in slavery, and gave Aleck his freedom.” But Edmund’s beliefs about slavery are not clear. No evidence exists to suggest Kirby Smith did manumit him. And as effusive as Darnes was in his praise of the general, Darnes does not say he was freed by the general’s order.

Darnes does say he reveled in the hustle-bustle and responsibility of carrying swords and guns: “The sight of the soldiers and their equipments and their horses was grand to me.” Of Kirby Smith, he wrote, “I would follow him everywhere he went: the soldiers quarters, and the stables.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bf/58/bf58d9e9-8785-4bcb-ac35-3129e29e3813/janfeb2023_c07_confederate.jpg)

Young Darnes accompanied Kirby Smith to the Bull Run battlefield, retreating to a fence and then the rear as fighting got “so hot and heavy.” After being separated from the general and hearing reports of his death, he found Kirby Smith lying wounded. Cassie picked up the story: Darnes had saved for posterity and for “Ole Miss”—Edmund’s mother, Frances—“the blue flannel bloody shirt which he had taken off his general when he was removed from the battlefield.” According to Cassie, “He never tired of telling of his ‘Marse Edmund’s’ deeds of bravery.”

After Lee surrendered, Edmund Kirby Smith fled to Mexico and Cuba to evade punishment for serving the Confederacy. It was Darnes who ushered Cassie Kirby Smith and the couple’s two children, along with their belongings and horse, to safer quarters in Virginia. In November 1865, Kirby Smith returned and took an oath of amnesty, pledging allegiance to the reconstituted United States. Darnes remained part of the growing household as a free man until 1867, well after emancipation was the law of the entire land. Fear and caution may have kept him in place. Where would he and his aging mother work and live? Did they consider St. Augustine their home? Staying with the Kirby Smiths for a time—and for pay—could have seemed a safer move than leaping into the unknown.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/9f/8f9fc338-4b71-492b-a8f5-e337553e5aee/janfeb2023_c02_confederate.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/92/45/92456b68-27e9-4c81-96dc-36f78493492c/janfeb2023_c03_confederate.jpg)

Or did Darnes feel some lingering sense of loyalty? Indeed, he noted with apparent gratitude that Kirby Smith had whipped him only once, for accidentally letting a dog escape. We don’t know how old Darnes was at the time of this incident, but when he retold the story in the 1893 eulogy letter, he still remembered his confusion: “I did not know and could not understand why I was being punished,” he wrote. “I would say as best I could, ‘I ain’t done nothing, I ain’t done nothing.’” Darnes said he felt so “bad over the circumstances that I took leave of absence without permission for two days.” After he came back, he recalled, Kirby Smith “spoke very kindly to me, but I was thinking that death was better for me, and said to him to kill me, that I did not want to live. I am proud to say he never laid the weight of his hand on me for anyone, not even his own wife.” In the next sentence, he added diplomatically, “I don’t know she ever wished him to.”

In 2001, a great-great-granddaughter of Edmund Kirby Smith reached out to the St. Augustine Historical Society. Maria Kirby-Smith (who hyphenates her last name, like many in the family today) is an artist in Camden, South Carolina, and she wanted to create a statue of her famous Confederate ancestor, funded by her family. It would be placed prominently in the courtyard of the society’s headquarters and just visible to passersby through an arched entrance on Aviles Street. The Spanish Colonial-style building that now houses the historical society was once her family’s ancestral home and was the literal birthplace of the general himself (and likely of Darnes).

The historical society’s research librarian, Charles Tingley, remembers hearing about the proposed sculpture alongside the society’s then-executive director, Taryn Rodriguez-Boette. “Well, that’s all very good,” was the response. “We’ll bring it up to our board of trustees.” Then came the kicker: “You know,” the sculptor said, “I’d really like to include Aleck.” Rodriguez-Boette and Tingley looked at each other. “Who’s Aleck?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a7/e0/a7e0f1d4-c44d-4c5a-9443-66df20fd07a0/janfeb2023_c18_confederate.jpg)

Tingley, hunting for living relatives of Darnes, scanned microfilm rolls, online newspaper databases, musty volumes about pioneering doctors of Florida, book indexes and conference proceedings. Over the next 20 years, he filled two boxes with newspaper mentions, probate records detailing Darnes’ estate after his 1894 death, and photographic calling cards popular during the 19th century. As painstaking as Tingley’s research has been, the two boxes of materials stand in stark contrast to the voluminous historical footprint left by Kirby Smith. Maria, for her part, had read about Darnes in Cassie’s memoir. She told me, via email, not to mistake her for a Confederate enthusiast. “The ‘Anthem of Southern history’ was not played during my upbringing.” Her father, like many of his male ancestors before him, had been a West Point graduate, and his career as an Army engineer meant many moves.

“We traveled light, a minimum of furniture, no ancestral portraits,” Maria wrote in her email. In other words, her family hadn’t followed the path of forebears who’d enthusiastically embraced their pedigrees and worked to preserve the history of their ancestors and the Confederacy. (One of Edmund and Cassie’s daughters, Nina, wrote to Confederate Veteran magazine in 1898 to dispute a claim that another general—not her father—had “saved the day” at Manassas.) Still, Maria had something in common with those ancestresses who collected relics of the Confederacy and raised funds for the monuments that are now falling around the country: a desire to leave a historical mark on the landscape.

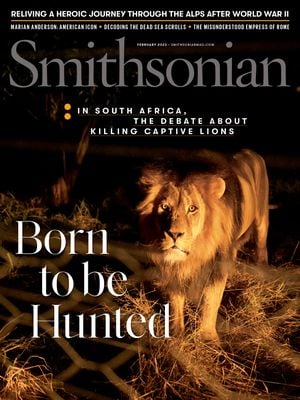

Maria, compelled by illness and a recent inheritance, wanted to make a statement about her famous ancestor and his enslaved valet. The sculpture, installed in 2003 and titled Sons of St. Augustine, shows the two men in their later years, standing together like old friends. Maria calls it “a metaphor, an imagined meeting of the two older gentlemen. They had overcome adversities, each maturing into their true calling, and were honored in their professions and beloved by their communities.”

When Maria later asked my opinion of the statues, I floundered a bit. I had walked around the statues and admired the metallic ripples of Kirby Smith’s professor’s robes. I felt the power in locating a statue of Darnes there, where he was probably born into bondage and lived his early childhood in the attic or a long-ago demolished outbuilding. I absorbed the visual message in the statues standing at near-equal height. Russell Earl, Darnes’ great-great-great-nephew and a Jacksonville resident, recognized all those things, too; he emphatically told me that he loved the statue for showing Darnes as a man in his own right.

Therein lies the rub. Creative license empowers the artist, but in their lifetimes, Kirby Smith and Darnes could not have made equivalent claims to citizenship or humanity.

Critics pointed out as much. In 2016, amid rumblings over the general’s statue in the U.S. Capitol, the Tallahassee Democrat reported that Maria Kirby-Smith “was accused of being a revisionist and a Pollyanna” whose artwork bronze-washed her family’s slaveholding past. (She responded, “If we don’t stay on the side of the positive, we’ll never find the light.”)

Without the accompanying historical marker, a visitor would not know that one of these men had enslaved the other. Rather than the common visual tropes of slavery—chains or a barely clothed Black body, crouched in submission—Darnes’ sculpture depicts him with his doctor’s bag and Masonic fob. It indicates nothing about Darnes’ precarious journey from enslaved laborer to celebrated physician. The men might be old chums reunited for a moment.

Sculpture can be a narrative device for telling a story that’s more aspirational than actual. As I left the historical society, I wondered: What will viewers think those two figures are trying to say a century from now? I turned and looked at the statues one last time. Edmund Kirby Smith’s statue stretches out an arm in a goodwill gesture, or maybe a half-embrace. But from another angle, it looked like Darnes’ statue is keeping Kirby Smith’s at a careful arm’s length.

When Darnes died in Jacksonville in 1894, the Evening Telegram reported that more than 3,000 people crowded his funeral at Mt. Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church. Two bands played sacred music, and Masons marched in regalia. As a pastor read the funeral rites, the newspaper reported, “two pigeons flew to the top of the church and remained there. Some of the people present said that t’was angels that came to guard the soul home to heaven.”

The article noted that Darnes “had been a popular practicing physician in this city for about 16 years, and rendered valuable services during the smallpox and yellow fever epidemics.” In 1867, Darnes had left the Kirby Smith family and moved north for an education. Edmund Kirby Smith’s older sister Frances Webster, a known Union sympathizer, had taught Darnes to read before the Civil War. First, he went to Pennsylvania and attended Lincoln University, a historically Black college. Then he went on to the newly launched Howard University Medical School in Washington, D.C. After earning his medical degree, he returned to Florida and settled in Jacksonville.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/90/9f/909f1735-8993-4784-9566-e4eb4cad1f69/janfeb2023_c20_confederate.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/9e/2f9e6661-21d3-4d0b-aec6-0527cad6eb54/janfeb2023_c16_confederate.jpg)

Little is known about what Darnes actually did to care for patients. After his death, his estate records showed an operating table and obstetric textbooks among his belongings, suggesting that he may have delivered babies. Equally little is known about his day-to-day role during yellow fever outbreaks. A bulletin by the Jacksonville Auxiliary Sanitary Association, a public health agency that essentially took over the city during the 1888 outbreak, listed Darnes among the local physicians specially employed to combat the crisis. Darnes had likely encountered the sometimes-fatal disease that came with jaundice and black vomit well before he trained as a doctor. Edmund Kirby Smith had contracted yellow fever in Texas in 1853; military pay vouchers show Darnes was with him in the early months of the year. A teenaged Darnes may have been by Kirby Smith’s side during his illness and recovery, ministering to him even then.

Decades later in Jacksonville, Darnes was likely beloved because of what he didn’t do: leave the city. In September 1888, a Boston medical journal projected that 2,000 to 3,000 people—of 3,945 remaining white residents and 9,812 Black ones—would leave Jacksonville in less than two weeks; it noted that at least a third of the remaining Black residents did not have the means to leave or worried that uprooting themselves would mean losing their right to vote. Other Black people headed into the city after hearing a rumor that the federal government had sent relief earmarked for local Black communities. But relief agencies complained of loafers and were quick to expect trouble from groups they called “unruly colored people”—a charge refuted vociferously by Black ministers. Meanwhile, Jacksonville’s mayor, who was visiting Ohio at the time, didn’t return—supposedly due to pneumonia, but the story made locals scoff and seethe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/cd/6bcdf41d-3edf-44b3-aa19-84774dcaf0ce/janfeb2023_c04_confederate.jpg)

It was not yet accepted that the disease was spread by mosquitoes. Instead, city officials and the sanitary association took drastic and unproven measures such as firing cannons of sulfureous gas to disperse “sick air.” Burnings of “infected” bedding also made Jacksonville a smoky hellscape, and federal and state officials mulled over measures that would permit destruction of any dwelling where yellow fever cases had been detected. Railways across the South banned travelers and baggage from Jacksonville and established temporary quarantine houses to keep new arrivals from mingling with the locals.

Meanwhile, the mass exodus created a demographic shift in Jacksonville, leaving opportunities for Black politicians and civic entrepreneurs. The city in which Darnes quite successfully plied his trade was at once segregated and opening. When newspapers reported the yellow fever dead, they often separated the tallies by race. But with Black residents forming a higher percentage of the population than before, Black voters became important blocs that white politicians could not avoid. In fact, white politicians had to woo them if they wanted electoral victory, which also meant overturning measures like the poll tax. Throughout most of the South, Black voters were allied with the Republicans, the party of Lincoln. But in Jacksonville, even the rising Democratic Party, marked elsewhere by terrorism against Black constituents, courted Black residents. “Fusionist” coalitions—interracial political networks that had short-lived moments across the South after the Civil War—put Black people in the all-too-temporary catbird seat. In 1887, five Black men were elected to the City Council, an unprecedented win.

This time period—and Darnes’ possible role in it—fascinates Gerald Urso, a lay historian and general contractor who specializes in historical renovations. Urso contends that Jacksonville had as vibrant a history as “Black Wall Street” cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Durham, North Carolina. Urso lists the names of Black lawyers, doctors and institution-builders whose energy and race-based activism fueled the city from emancipation all the way through the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century. This 1880s version of the “greatest generation” had its center of gravity at the Most Worshipful Union Grand Lodge of Florida, a Black Masonic order to which Urso belongs today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/c6/7bc6a128-8098-4e1c-aa13-f5861f4145bd/janfeb2023_c11_confederate.jpg)

“Look at Harmony Lodge, No. 1, which Darnes belonged to,” Urso told me. “You had congressmen; senators, including men such as Joseph Lee, the city’s first Black lawyer and later a member of the state House.” Many of the lodge’s records were destroyed in the city’s 1901 fire, but Urso found evidence in other archives that Darnes wasn’t just a member but a grand master. And he had exacting standards. Time and time again, he reported fellow Masons for conduct considered unbecoming.

Like Tingley, Urso is a walking compendium of facts about his elusive historical subject. He can rattle off citations: Have you read the James Weldon Johnson memoir that describes a meeting with this “strange creature, the colored doctor,” who taught Johnson how to fish and gave him nickels to learn the sign language alphabet as a child? Or Darnes’ letter to a Florida newspaper setting the record straight about the time a leader of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination was forced to leave a train for no apparent reason but his color? Urso believes wholeheartedly that Darnes was a “race man” actively dedicated to his Black community, unafraid to publicly call out discrimination, and hardly one to soft-pedal slavery.

On a steamy morning in August, I rode in Urso’s truck along the gleaming ribbon of asphalt that bisects the back reaches of Jacksonville’s Old City Cemetery. To the left, white tombstones shimmered brightly. To the right, the rows of graves were not so well defined, the grass was a bit weedier, and food wrappers blew past whenever a breeze deigned to stop by. I could see, without needing Urso to tell me, which side of the road was the old “colored” burial ground.

Once we got out of the truck, Urso moved with unerring focus, pointing out the luminaries interred on the grounds. Over there, the mausoleum of Laura Adorkor Kofi, a Ghanaian-born follower of Marcus Garvey and self-proclaimed prophet. Sprinkled here and there, the graves of a few Black Union soldiers, part of a force that occupied the city in 1863—much to the horror of white residents. Their final resting place was just a few long strides away from the tidy markers to Confederate dead on the other side of the path.

I followed slowly, scratching mosquito bites and skirting large stones that tend, in very old burial grounds, to signal otherwise unmarked graves. Behind me walked Darnes’ great-great-great-nephew Russell Earl, a retired postal worker.

Earl knew little about his ancestor until he was approached by Tingley, who was searching for living relatives as well as old documents related to the doctor. “I only knew what my grandmother had said, that there was a doctor somewhere in the family,” said Earl, wearing a purple polo emblazoned with Masonic symbols. Like his ancestor, and Urso, Earl belongs to the Most Worshipful Union Grand Lodge of Florida.

Earl’s family had retained something of Darnes’ legacy, if they didn’t entirely understand why: his name. Russell Earl’s middle name is Alexander. Same for his first cousin, Reginald, and same for Earl’s son and grandsons. Seven people in four generations have borne the name even as familial memory of Darnes slipped away.

I walked with the two men to Darnes’ grave, which Urso and another Mason clean from time to time. It was topped with a small, wilted U.S. flag and a gray headstone showing two hands clasped in unity or greeting. Even though Darnes died in 1894, the local Sons of Confederate Veterans camp met members of the Earl family and replaced Darnes’ previous damaged gravestone in 2013 with this newer memorial.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b9/80/b980bb42-d60a-4f50-845e-f8b6140e432c/janfeb2023_c12_confederate.jpg)

According to its website, the Jacksonville chapter of the Confederate descendants’ organization is among the most active in the nation. It is named Kirby Smith Camp 1209. Calvin Hart, a representative of the camp, said via email, “We raised the funds and restored his grave because it was the right thing to do.” Along with Darnes’ presence alongside Kirby Smith in battle (though not as combat personnel), Hart noted, “He served the community of Jacksonville with distinction during a critical time.”

It’s not hard to understand why Sons of Confederate Veterans might want to celebrate a local Black luminary who wrote so glowingly of a Southern war hero and slaveholder. But was Darnes’ sanguine view of his bond with Kirby Smith some form of Stockholm syndrome, a controversial condition where a hostage identifies with his kidnapper? When I asked Urso what he thought, he sighed, saying, “I think there was love there.” Had Darnes been treated better or differently than an enslaved worker toiling in a field in Alabama? “Probably, yes,” he answered his own question. “But was it still a situation of ‘I’m better than you’? I’m sure.”

Urso was especially struck by the way Darnes described the beating he received at Kirby Smith’s hands. “I don’t know if there’s a 19- or 20-year-old brother who’s never beaten his 15-year-old brother,” he mused. “I don’t know if it was a mentally incestuous relationship, or if there wasn’t an actual brother-brother sibling relationship. I find it interesting that he did take him everywhere. Like, he didn’t need an 11-year-old to go with him in the battle.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a3/f3/a3f3ffde-0926-4c2a-9690-f6d679919edf/janfeb2023_c19_confederate.jpg)

As if there weren’t enough questions, some of these latter-day Darnes detectives speculate that the two men bear an uncanny resemblance and that they might be connected by blood—perhaps brothers or some other kinfolk.

Photographs of Kirby Smith and Darnes have sparked some of this discussion. Maria Kirby-Smith didn’t have a picture of Darnes until well into her sculpting process. But when she finally got one, she thought there was a resemblance—as did Tingley, Urso and Earl. Both men had a receding hairline and prominent forehead. Both had deep-set eyes. But perhaps the two men looked somewhat alike because they were balding, of a certain age, dressed formally and frozen in the stony-faced gaze required for 19th-century photography. Genetic testing of surviving Darnes and Kirby Smiths likely would not help. Darnes left no direct descendants; Russell Earl’s lineage came from Darnes’ sister, believed to be a half-sister with a different and likely Black father.

Darnes’ paternity will probably remain an open question. There’s little information about the years between his departure from the Kirby Smith household and his graduation from Lincoln University, but somewhere, he acquired his full name: Alexander Hanson Darnes. Tingley discovered that Darnes’ mother, Violet, had been hired out at some point before his birth to a Lt. Alexander Hanson Darne, so he tops the list of candidates for her son’s paternity.

Sexual exploitation of bondswomen was a linchpin upon which slavery revolved. Darnes’ father could have been one of the Kirby Smiths’ frequent visitors, a man off the street, a secret lover—or someone in the household. Edmund’s father, Joseph, was a possibility. (For that matter, so was Edmund himself—though he was mostly away at school and was a teenager, roughly the same age as Violet, when Aleck was born.) White slave owners often increased their wealth by fathering children by enslaved women. In the mid-1800s, South Carolina diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, wife of Senator James Chesnut, acerbically observed, “Like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines; and the mulattos one sees in every family partly resemble the white children. Any lady is ready to tell you who is the father of all mulatto children in everybody’s household but her own. Those, she seems to think, drop from the clouds.”

Was Frances Kirby Smith, Edmund’s mother, a woman whose husband or male relative fathered such a child? In the early 1840s, around the time of Darnes’ probable birth, the hot-tempered Connecticut-born woman left her spouse and refused to return for months. It was an unusually radical move for a woman in a society where divorce was not an option.

Darnes’ letter, of course, says none of these things. On the one hand, it seems a straightforward account. On the other, it invites multiple interpretations. Darnes could have been simply writing to the brief, eulogizing his former owner, and hewing to the common postmortem cultural philosophy of not speaking ill of the dead. He may have been influenced by the fact that his remarks were initially intended to be published in a Confederate veterans’ journal.

But there is a moment when Darnes might have deviated from his paean to the Kirby Smith family. On the second page of the letter, someone—probably Darnes himself, as the ink color matches his script—struck through the line, “A good and happy relationship always existed between master and servant.” He never calls himself a slave, rather a servant, though the terms were often used interchangeably in his time. Speaking of Kirby Smith’s mother, whom even her descendant Maria referred to as a “harridan,” Darnes wrote, “She was good and kind to me.” Again, he or some editor marked out part of the sentence that would have made it read: “She was as good and kind to me as she could be.” Darnes’ letter is the interpretive challenge that keeps on giving: Those crossed-out words could be read as an uncomplicated turn of phrase—or as a sly question about whether slavery was compatible with kindness. But Darnes then went on to unambiguously shout out Edmund’s sister, who had taught him to read, calling her a “most fortunate and Christian-hearted lady who pitied the unfortunate condition of this part of humanity.”

The historian Erin Austin Dwyer, author of Mastering Emotions: Feelings, Power and Slavery in the United States, has some ideas about why Darnes’ letter might have downplayed the mistreatment inherent in enslavement. Bondspeople concealed their true feelings in order to survive. They smiled and nodded even when insulted. Young Frederick Douglass saw enslaved parents beaten for sobbing too much when their children were sold away. Slaveholders also had reason to mask their feelings: To control others required taming one’s own temper. Being passionate, violent, sentimental or soft were liabilities and undermined the capacity to rule wisely.

Dwyer emphasized that Darnes was walking a fine line in his letter, contending with the legacy of his past as well as the politics of his present. She noted that Jourdon Anderson, the freedman who wrote that sly yet scathing response from Ohio to his former master in Tennessee, was able to be so bold because he was “fully out of the financial power, out of the geographic scope, out of the legal power of his former owner. But of the many things that strike me reading Darnes is, yeah, he’s still in Florida at the height of Jim Crow.” After all, she pointed out, “Ida B. Wells wrote her famous anti-lynching pamphlet ‘Southern Horrors’ a year before” and faced lynching threats for truth-telling.

Was Darnes being careful and gracious in that letter at least in part because the memory of Edmund Kirby Smith was currency? Did he need a favor from Cassie Kirby Smith or someone in that family’s network? Playing into the Lost Cause narrative of happy slaves and bighearted Confederates could have helped Darnes preserve his safety and reputation. Saying the wrong thing might have endangered his business or his very life. Even with the power and prestige Darnes had accrued in Jacksonville by 1893, Dwyer believes Darnes didn’t “have full liberty to be saying everything he wanted to about Kirby Smith, even if he loathed him every moment of his life.”

Even so, she allows for something Freudian theorists call “cupboard love,” when a child attaches to an adult who might feed or otherwise give him or her something needed. Such feelings aren’t less real even if they’re forged in deplorable circumstances—in this case, during a childhood of unpaid labor spent on the literal warpath. She tries not to deprive enslaved people of a full slate of emotions, even when their feelings run contrary to modern sensibilities. “Emotions are sticky, messy things in the present,” she said. “Why should they be nice and neat in the past?”

:focal(2250x1693:2251x1694)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/41/0e/410e184d-3b6a-4310-a405-d608bfe4c25c/opener_-_janfeb2023_c15_confederate.jpg)