The Early History of Football’s Forward Pass

The forward pass was ridiculed by college football’s powerhouse teams only to be proved wrong by Pop Warner and his Indians

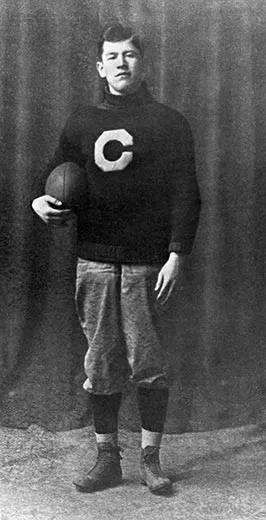

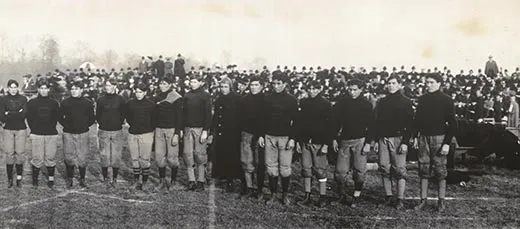

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/football-forward-pass-Carlisle-Indian-School-football-squad-631.jpg)

By 1905, college football was all the rage, attracting tens of thousands of fans to games at a time when major-league baseball teams often attracted only 3,000—and pro football was still more than a decade away. But it was also an increasingly violent and deadly passion. There were 18 fatalities nationwide that year, including three college players (the rest were high-school athletes), and President Theodore Roosevelt, whose son was on the freshmen team at Harvard University, made it clear he wanted reforms amid calls by some to abolish the college game. In a commencement address at the school earlier in the year, Roosevelt alluded to the increasingly violent nature of football saying, “Brutality in playing a game should awaken the heartiest and most plainly shown contempt for the player guilty of it.”

So in December representatives of 62 schools met in New York to change the rules and make the game safer. They made a number of changes, including banning the “flying wedge,” a mass formation that often caused serious injury, created the neutral zone between offense and defense and required teams to move 10 yards, not 5, in three downs.

Their biggest change was to make the forward pass legal, beginning the transformation of football into the modern game. But at first, it didn’t seem like a radical move. Established coaches in the elite Eastern schools like Army, Harvard, Pennsylvania and Yale failed to embrace the pass. It was also a gamble. Passes couldn’t be thrown over the line on five yards to either side of the center. An incomplete pass resulted in a 15-yard penalty, and a pass that dropped without being touched meant possession went to the defensive team. “Because of these rules and the fact coaches at that time thought the forward pass was a sissified type of play that wasn’t really football, they were hesitant to adopt this new strategy,” says Kent Stephens, a historian with the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Indiana.

The idea of throwing an overhand spiral was relatively new, credited to two men, Howard R. “Bosey” Reiter of Wesleyan University, who said he learned it in 1903 when he coached the semipro Philadelphia Athletics, and Eddie Cochems, the coach at St. Louis University.

St. Louis quarterback Bradbury Robinson completed the first legal pass on September 5, 1906 when he threw 20 yards to Jack Schneider in a scoreless tie against Carroll College (Robinson’s first attempt fell incomplete, resulting in a turnover). St. Louis went on to win the game 22-0. That completion drew little attention, but a month later a pass from Wesleyan’s Sam Moore to Irwin van Tassel in a game against Yale garnered more attention, including accounts in the press.

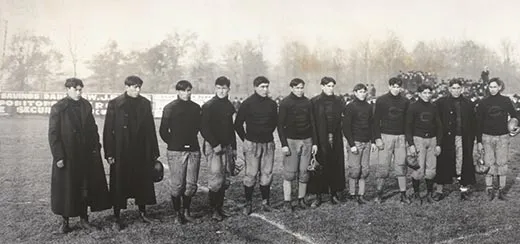

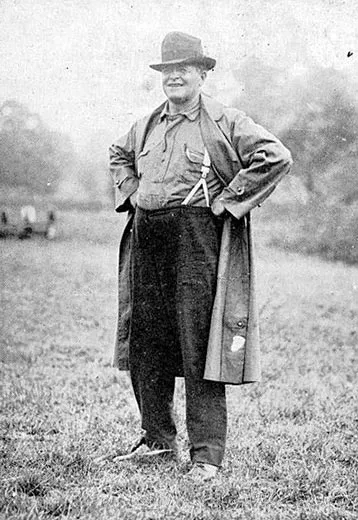

But it took another year and the team from Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School to showcase the potential of the pass. In 1907, Glenn Scobey (Pop) Warner had returned to coach at the boarding school for Native Americans that he’d built into a football powerhouse beginning in 1899, largely through trick plays and deception. Over the years, he drew up end arounds, reverses, flea flickers and even one play that required deceptive jerseys. Warner had elasticized bands sewn into his players’ jerseys so that after taking the kickoff, they would huddle, hide the ball under a jersey and break in different directions, confounding the kicking team. Warner argued there was no prohibition against the play in the rules. The tricks were how the smaller, faster Native Americans could compete against players 30 or 40 pounds heavier.

For the 1907 season, Warner created a new offense dubbed “the Carlisle formation,” an early evolution of the single wing. A player could run, pass or kick without the defense divining intent from the formation. The forward pass was just the kind of “trick” the old stalwarts avoided but Warner loved, and one he soon found his players loved as well. “Once they started practicing it, Warner pretty much couldn’t stop them,” says Sally Jenkins, author of The Real All Americans, a book about Carlisle’s football legacy. “How the Indians did take to it!” Warner remembered, according to Jenkins’ book. “Light on their feet as professional dancers, and every one amazingly skillful with his hands, the redskins pirouetted in and out until the receiver was well down the field, and then they shot the ball like a bullet.”

Carlisle opened the 1907 season with a 40-0 triumph over Lebanon Valley, then ran off five more victories by a total score of 148-11 before traveling to the University of Pennsylvania’s Franklin Field (still used today) to meet undefeated and un-scored upon Pennsylvania before 22,800 fans in Philadelphia.

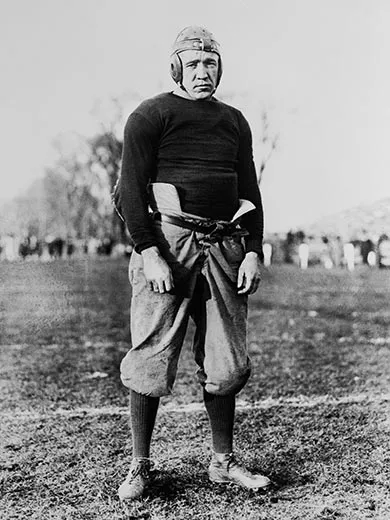

On the second play of the game, Carlisle’s Pete Hauser, who lined up at fullback, launched a long pass that William Gardner caught on the dead run and carried short of the goal, setting up the game’s first touchdown. The Indians completed 8 of 16 passes, including one thrown by a player relatively new to the varsity squad named Jim Thorpe. The sub-headline to the New York Times account of the game read: “Forward Pass, Perfectly Employed, Used for Ground Gaining More Than Any Other Style of Play.” The story reported that “forward passes, end runs behind compact interference from direct passes, delayed passes and punting were the Indians’ principal offensive tactics.”

According to Jenkins’ book, the New York Herald reported: “The forward pass was child’s play. The Indians tried it on the first down, on the second down, on the third down—any down and in any emergency—and it was seldom that they did not make something with it.”

Carlisle romped 26-6, outgaining Penn 402 yards to 76. Two weeks later, the Indians again used the pass to defeat Harvard, a team they’d never beaten, 23-15. Carlisle lost one game that year, to Princeton 16-0 on the road. The game had changed forever. In the ensuing decades, a Notre Dame victory over Army in 1913 somehow earned the reputation as the game that pioneered the use of the forward pass and changed football. Irish quarterback Gus Dorais completed 14 of 17 passes for 243 yards, some to an end named Knute Rockne, in a shocking 35-13 victory. By then, the rules had been changed to eliminate the penalties for incompletions and throwing the ball over the center of the line.

But Jenkins says the idea that Notre Dame created the modern passing game “is an absolute myth.” Newspaper story after newspaper story from the 1907 season details the Carlisle passing game. Even Rockne, she adds, attempted to correct the record later in life.

“Carlisle wasn’t just throwing one or two passes a game. They were throwing it half their offense,” she adds. “Notre Dame gets credit for popularizing the forward pass, but Pop Warner is the man who really created the passing game as we know it.”

Thorpe, who became an Olympic hero and one of the most celebrated athletes of the century, went on to play for Carlisle through the 1912 season, when Army Cadet Dwight Eisenhower was injured trying to tackle him during a 27-6 Indians victory. After the 1914 season, Warner left Carlisle for Pittsburgh, where he won 33 consecutive games. He went on to Stanford and Temple, finishing his coaching career in 1938 with 319 wins.

In 1918, the U.S. Army reoccupied the barracks at Carlisle as a hospital to treat soldiers wounded in World War I, closing the school. Carlisle ended its short stretch in the football limelight with a 167-88-13 record and a .647 winning percentage, the best for any defunct football program.

“They were the most innovative team that ever lived,” Jenkins says. “Most of Warner’s innovations he got credit for later were created in 1906 and 1907 at Carlisle. He was never so inventive again.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)