The Enslaved Woman Who Liberated a Slave Jail and Transformed It Into an HBCU

Forced to bear her enslaver’s children, Mary Lumpkin later forged her own path to freedom

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/0a/290a3037-d59a-4482-81f9-bd636e9ed774/lumpkin.jpg)

The cobblestone streets of downtown Richmond, Virginia, gently slope to a low-lying area where a dark history is hidden.

One of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, Shockoe Bottom is marked by throbbing nightclubs, an advertising agency, and a smattering of cafés, hotels and restaurants. Tobacco warehouses perched on the James River are now stylish lofts. Interstate 95 roars over the neighborhood, and Amtrak rails run alongside the highway, shuttling passengers to the historic Main Street Station. Old advertisements painted on the sides of brick buildings lend the neighborhood a certain charm. But it also feels abandoned and unloved, cluttered with parking lots and potholed streets.

In the shadow the train station, visitors find history delivered up on a dull brown sign: Lumpkin’s Slave Jail Archaeological Study Site. Three metal markers outline the jail’s significance, telling the story of one of the most important chapters of the domestic slave trade in America.

This is how the life of Mary Lumpkin, an enslaved woman who survived life inside the brutal jail, is shared. And this is exactly the way to tell a story so that no one will hear it.

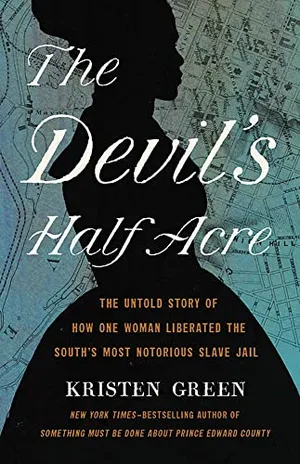

The Devil's Half Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South's Most Notorious Slave Jail

The inspiring true story of an enslaved woman who liberated an infamous slave jail and transformed it into one of the nation’s first HBCUs

Described as “nearly white” and “fair faced,” Mary, who was born in 1832, may have been the multiracial child of an enslaved woman and her enslaver, one of his relatives, or a white overseer. Sold away as a young girl, probably from one or both of her parents, she was purchased by the slave trader Robert Lumpkin, a violent white man 27 years her senior. When she was about 13, she was forced to have the first of five children with him. According to a descendant, she told him he could do with her what he wanted but demanded that their children be freed. She and the children likely lived with him on the compound of his slave jail, where he imprisoned thousands of enslaved people between 1844 and 1866. Some were imprisoned there before sale, and others were held after sale. Nearly all were eventually shipped away to the Deep South.

In this wretched place, Mary managed to educate her children and find a path to freedom, moving them and herself to the free state of Pennsylvania with Robert’s blessing prior to the Civil War. She inherited the jail in 1866, when Robert died and bequeathed the property to her. Two years later, she helped a white Baptist missionary from the American Baptist Home Mission Society turn the “Devil’s Half Acre”—a greatly feared place where countless enslaved people had long suffered—into “God’s Half Acre,” a school where dreams could be realized. The same grounds where enslaved people were imprisoned and beaten became the cornerstone for one of America’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU). Virginia Union University (VUU) is still in existence today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/b4/58b4b01c-a8d4-4477-a975-28a02c5f5316/image-asset.jpeg)

“Virginia Union ... was born in the bosom of Lumpkin’s Jail,” says W. Franklyn Richardson, chairman of the university’s board and an alumnus. “The place we were sold into slavery becomes the place we are released into intellectual freedom.”

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the school, founded as the Richmond Theological School for Freedmen, provided Black students with an education. For more than 150 years, it has elevated and nurtured generations of Black men and women, helping them to realize their potential. It has shaped civic, education and business leaders and developed activists who worked to desegregate whites-only lunch counters in Richmond department stores.

It is also one of the rare HBCUs in America that can tie its origins to a Black woman.

“For Virginia Union to have a forming story rooted in Black womanness ... it’s a story of its own,” says VUU president Hakim J. Lucas.

Yet for many years, Mary was invisible, even at the school she had played a role in forming. She lived first as an enslaved woman in the Richmond slave trade district and then as a free person in Philadelphia; New Orleans; and, later, New Richmond, Ohio. When Lumpkin’s Jail was demolished and covered with fill dirt in 1876, her story went with it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fd/d8/fdd885c7-eb2f-4c53-b505-79dfe2551719/iiif-service_gmd_gmd388_g3884_g3884r_cw0645600-full-pct_125-0-default.jpg)

Few enslaved people left the kinds of documents that historians use to trace and tell white people’s stories. Though Mary, who died in 1905 at the age of 73, was literate, she did not leave journals or personal papers. “People who are free have the ability to give their papers to someone specific,” says Niya Bates, the former public historian at Monticello. “Enslaved people didn’t have that privilege.”

Most enslaved people kept everything in their minds—“the only diary in which the records of their marriages, births and deaths were registered,” wrote Henry Clay Bruce, who was born enslaved in Virginia, in his 1895 autobiography. Oral histories were their primary means for preserving stories.

A handful of letters that Mary wrote to the administrators of the school now known as Virginia Union University survive today. These letters and the court testimony she gave on behalf of a friend are the only records in her own voice. I couldn’t find any documents that show where Mary was born or who her parents were.

To reconstruct the lives of Black men and women, historians have had to rely on the records created by their oppressors. But such records are unavailable for Mary, as only a few pages of a ledger book from Robert’s infamous slave jail operation were preserved. While his will instructed that his assets be distributed to Mary, and to their children if she eventually married, other documents that might have revealed more about the relationship—and more about his role in the slave trade—were either lost or destroyed, perhaps intentionally.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fb/2a/fb2ace5b-72b8-4419-9ca8-f50ae25a5dd5/2560px-another_aerial_look_of_lumpkins_jail_site.jpeg)

To flesh out Mary’s story, I went to a Richmond courthouse, where crinkling, 150-year-old court cases were still tied in “red tape”—the ribbon that has become synonymous with government bureaucracy. I traveled to the tiny seaside town of Ipswich, Massachusetts, and sat in the town museum and town library, flipping through records for the school her two white-passing daughters attended. Robert had agreed to educate them, as he feared that a “financial contingency might arise when these, his own beautiful daughters, might be sold into slavery to pay his debts,” according to Charles Henry Corey, a leader at the Richmond theology school.

Poring over old property records in a Philadelphia basement, I discovered that Mary had purchased a home in the Pennsylvania city in her own name. The girls went to live there with their two eldest brothers after two years of schooling, and Mary and her youngest son joined them before war broke out in 1861. I visited the hillside cemetery where she was buried in New Richmond, Ohio, and learned about the abolitionist roots of the community on the banks of the Ohio River where she spent her later years. An outline of a life began to emerge that seemed to be defined as much by the freedom that Mary forged in her late 20s as by her enslavement.

As I traced her movements, I discovered that in her role as the mother of Robert’s children, Mary was part of a community of girls and women, hidden from view, who were chosen as sexual partners by slave traders and forced to bear their children. These women probably managed their enslaver’s household and operated some part of the business of running his slave jail. As witnesses to the slave traders’ violence and participants in the system of slavery, they were in some ways separated from other enslaved people. Yet choices were not theirs to make. They were unfree, and their lives were a paradox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/06/c6/06c65625-1da6-4539-bc6a-153a3a99ec74/dmd-2008-1216-1030.jpeg)

These enslaved women may have encouraged each other to seek more independence and assert themselves in the slave jails and in their relationships with the fathers of their children. Perhaps they supported each other in their quests to educate themselves and their children. They may have bolstered each other’s attempts to move their children out of slavery. Maybe they shared not only tactics for enduring their lives of enslavement but also methods for seeking better lives.

Mary forged such friendships and connections throughout her adult life. Her relationships with other enslaved women, including Lucy Ann Cheatham Hagan, Corinna Hinton Omohundro and Ann Banks Davis, may have helped protect her in her interactions with Robert and must have made her daily life easier to bear.

In her relationship with Robert, Mary exercised her agency and limited authority, finding a way out of enslavement. She showed empathy and concern for other enslaved people who were tortured and held captive in Lumpkin’s Jail. She was highly mobile, seeking out opportunities in new places, and she would eventually make a home for herself in three American cities and a village. Not only did Mary ensure that her children were educated, but she helped make education available to newly free Black men in the aftermath of the Civil War and, subsequently, to generations of Black Americans. Why, then, don’t we know her story?

Traditionally, only the stories of the most exceptional women—like Harriet Tubman—and their narratives of triumph have broken through. But focusing solely on those who escaped slavery leaves out the reality of most enslaved women’s lives. Many felt that they could not run away because they had family obligations and children they would not leave. “[A]pparently many women concluded that permanent escape was impossible or undesirable,” writes the late historian Stephanie M. H. Camp.

Instead, they fled temporarily when violence became too great to withstand. They fought back to avoid abuse, and they protested beatings. When they could not avoid rape, they attempted their own birth control and chewed cotton root to abort pregnancies. In despair and defiance, some took the lives of their own infants rather than see them grow up enslaved. A few killed their enslavers. Others slit their own throats, cut off their own hands, jumped from windows. They rescued other enslaved people, and they led slave revolts—stories that are only now coming to light.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/80/e980987d-b161-4484-b42d-710ae9de8d3a/awaitingsale_c3330d46da.png)

They resisted in quiet ways too, using their agency to secure better jobs in enslavers’ households, to get education for their children, to provide their families with some security and extra food. Because historians for generations have limited the scope of storytelling about Black women to those who are better documented and those deemed exceptional, the lives of women like Mary have not been explored.

Mary’s story was even forgotten by her own family. Using public documents and newspaper stories, I built her family tree and traced the movement west of several of her children, followed by her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. During Reconstruction and Jim Crow, they headed farther and farther away from the land of her birth and enslavement, from her Blackness, from all that she endured and all she survived—until many of her descendants didn’t know that she had existed at all.

Black scholar and writer Carolivia Herron has always known the story of her ancestor Mary, who insisted to her enslaver that “these children have to be free.” When Herron visited the Lumpkin’s Jail site in 2014, she threw herself onto the ground at the adjacent African Burial Ground and whispered to her great-great grandmother and other long-suffering kin. “You won’t be forgotten,” she said. “I will hold you up.”

Adapted excerpt from The Devil's Half Acre: The Untold Story of How One Woman Liberated the South's Most Notorious Slave Jail. Copyright © 2022. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.