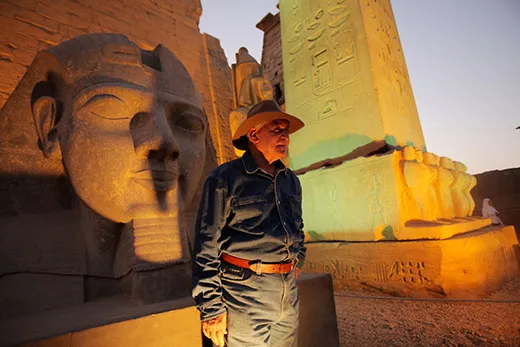

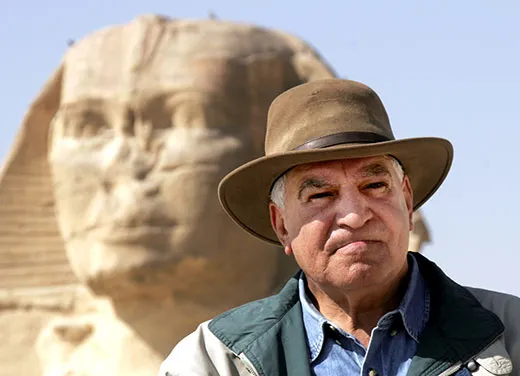

The Fall of Zahi Hawass

Removed as minister of antiquities, the high profile archaeologist no longer holds the keys to 5,000 years of Egyptian history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Zahi-Hawass-Egypt-631.jpg)

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect developments after Hawass was initially fired. (UPDATED 07/26/2011)

It is not as dramatic as the collapse of an ancient Egyptian dynasty, but the abrupt fall of Zahi Hawass is sending ripples around the planet. The archaeologist who has been in charge of Egypt’s antiquities for nearly a decade has been sacked in an overhaul of the country’s cabinet.

After several days in which his status was unclear—the appointment of a successor was withdrawn, leading to reports that Hawass would return temporarily—he confirmed by e-mail that he was out.

The antipathy toward Hawass in Egypt may be difficult to grasp in the West, where he is typically found on American television, fearlessly tracking down desert tombs, unearthing mummies and bringing new life to Egypt’s dusty past. But in Egypt he was a target of anger among young protesters who helped depose President Hosni Mubarak in February. Hawass had been accused of corruption, shoddy science and having uncomfortably close connections with the deposed president and first lady⎯all of which he vociferously denied. Many young archaeologists also demanded more jobs and better pay⎯and they complained Hawass had failed to deliver. “He was the Mubarak of antiquities,” said Nora Shalaby, a young Egyptian archaeologist who has been active in the revolution.

On July 17, Prime Minister Essam Sharaf removed Hawass, 64, as minister of antiquities, arguably the most powerful archaeology job in the world. The ministry is responsible for monuments ranging from the Great Pyramids of Giza to the sunken palaces of ancient Alexandria, along with a staff of more than 30,000, as well as control over all foreign excavations in the country. That gives the position immense prestige in a country whose economy depends heavily on tourists drawn by Egypt’s 5,000-year heritage.

“All the devils united against me,” Hawass said in an e-mail afterward.

Sharaf named Cairo University engineer Abdel Fatta El Banna to take over but withdrew the appointment after ministry employees protested that El Banna lacked credentials as an archaeologist. On July 20, Hawass told the Egyptian state news agency he had been reinstated, but it was unclear for how long. Six days later, Hawass said in an e-mail that he was leaving to rest and to write.

Finding a replacement may take time, foreign archaeologists said. In addition, the ministry of antiquities may be downgraded from a cabinet-level agency.

Mubarak had created the ministry in January as part of an effort to salvage his government; it had been a non-cabinet agency called the Supreme Council of Antiquities, which reported to the ministry of culture. The possibility that ministry would be downgraded, reported by the Los Angeles Times, citing a cabinet spokesman, worried foreign archaeologists. “I’m very concerned about the antiquities,” said Sarah Parcak, an Egyptologist at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. “And these monuments are the lifeblood of the Egyptian economy.”

Hawass had risen from the professional dead before. Young archaeologists gathered outside his headquarters February 14 to press for more jobs and better pay. He was accused of corruption in several court cases. And in March he resigned from his post, saying that inadequate police and military protection of archaeological sites had led to widespread looting in the wake of Egypt’s revolution. But within a few weeks, Sharaf called Hawass and asked him to return to the job.

In June, he embarked on a tour to the United States to encourage tourists to return to Egypt—a high priority, given that Egypt’s political upheaval has made foreign visitors wary. Egyptian officials said in interviews last month that Hawass’ ability to persuade foreigners to return was a major reason for keeping him in his position.

Hawass rose to power in the 1980s, after getting a PhD in archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and being named the chief antiquities inspector at the Giza Plateau, which includes the pyramids. In 2002, he was put in charge of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. He began to call on foreign countries to return iconic antiquities, such as the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum and the Nefertiti bust at the Neues Museum in Berlin. At the same time, he made it easier for foreign museums to access Egyptian artifacts for exhibit, which brought in large amounts of money for the Egyptian government. In addition, he halted new digs in areas outside the Nile Delta and oases, where rising water and increased development pose a major threat to the country’s heritage.

Hawass also began to star in a number of television specials, including Chasing Mummies, a 2010 reality show on the History Channel that was harshly criticized for the cavalier way with which he treated artifacts. In addition, Egyptians complained that there was no way to know what was happening to the money Hawass was reaping from his book tours, lectures, as well as his television appearances.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/andrew2.png)