The Financial Panic of 1907: Running from History

Robert F. Bruner discusses the panic of 1907 and the financial crisis of 2008

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1907panic_631.jpg)

Robert F. Bruner is the dean of the University of Virginia's Darden Graduate School of Business Administration. Last year, he and Sean D. Carr, the Director of Corporate Innovation Programs at the Darden Schools' Batten Institute, published "The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned From the Market's Perfect Storm," detailing a historic financial crisis eerily similar to the one now gripping Wall Street.

What was the Panic of 1907, and what caused it?

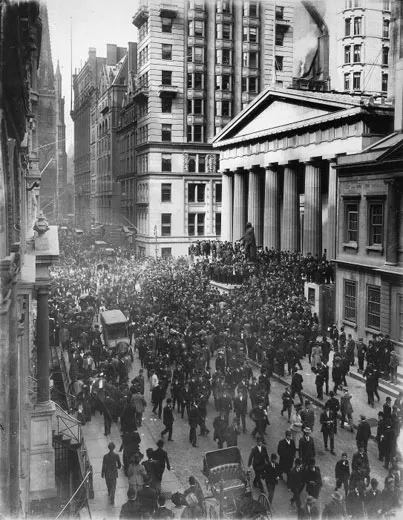

The Panic of 1907 was a six-week stretch of runs on banks in New York City and other American cities in October and early November of 1907. It was triggered by a failed speculation that caused the bankruptcy of two brokerage firms. But the shock that set in motion the events to create the Panic was the earthquake in San Francisco in 1906. The devastation of that city drew gold out of the world's major money centers. This created a liquidity crunch that created a recession starting in June of 1907.

In 2008 , is the housing market the culprit this time?

Today's panic was triggered by the surprising discovery of higher defaults on subprime mortgages than anybody expected. This discovery occurred in late 2006 and early 2007. A panic always follows a real economic shock; panics are not random occurrences of market emotions. They are responses to unambiguous, surprising, costly events that spook investors.

But the first cause of a panic is the boom that precedes the panic. Every panic has been preceded by a very buoyant period of growth in the economy. This was true in 1907 and it was true in advance of 2007.

What are the differences between the panic of 1907 and the crisis of 2008?

Three factors stand out: higher complexity, faster speed and greater scale.

The complexity of markets today is magnitudes higher than a century ago. We have subprime loans that even the experts aren't sure how to value. We have trading positions, very complicated combinations of securities held by major institutions, on which the exposure is not clear. And we have the institutions themselves that are so complicated that it's hard to tell who among them is solvent and who is failing.

Then there is greater speed: we enjoy Internet banking and wire transfers that allow funds to move instantaneously across institutions across borders. And news now travels at the speed of light. Markets react immediately and this accelerates the pace of the panic.

The third element is scale. We've just past the TARP, the Troubled Asset Relief Program, funded at $ 700 billion. There may be another $500 billion in credit default swaps that will need to be covered. And there are billions more in other exposures. We could be looking at a cost in trillions. In current dollars, these amounts may well dwarf any other financial crisis in history. In terms of sheer human misery,the Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression still overshadow other financial crises, even today's. But we aren't done with the current crisis; surely it already stands out as one of the largest crises in all of financial history.

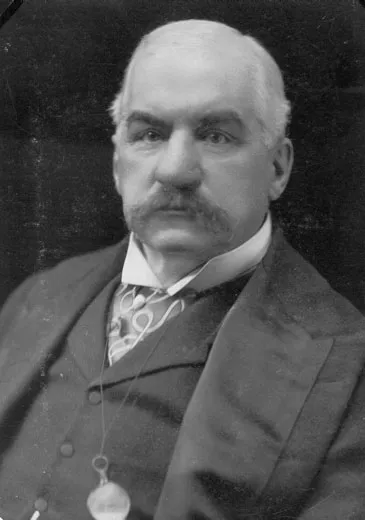

Describe J.P. Morgan and how he fit into Wall Street's culture in 1907.

J.P. Morgan was 70 years old at the time of the Panic. He was in the twilight of his extraordinarily successful career as a financier of the boom era, the Gilded Age of American expansion from 1865 to roughly 1900. He had engineered the mergers of firms that we would recognize today as still dominant—U.S. Steel, American Telephone and Telegraph, General Electric and the like. He was widely respected. In fact, the popular press personified him as the very image of the American capitalist. The little fellow on the Monopoly box with the striped pants and the balding head looks vaguely like J.P. Morgan.

He was a remarkable person. He had deep and extensive relations throughout the financial and business communities, and this is one of the keys to the leadership he exercised in the panic. He was a man of action; he galvanized people.

What did Morgan do to stop the panic?

You quell panics by organizing collective action to rescue institutions and generally convey confidence back into the market. Morgan was called back from Richmond, Va. by his partners when the panic hit. He took the equivalent of a red-eye flight, attaching his private Pullman car to a steam engine and hurtling back to New York City overnight. He arrived on Sunday, October 20th and immediately convened a meeting of the leading financiers at his mansion on 34th Street. He chartered working groups to get the facts and then over the next several weeks deployed the information to organize successive rescues of the major institutions. He did allow some institutions to fail, because he judged that they were insolvent already. But of the institutions that he declared he would save, every one survived.

Was Morgan practicing a kind of "profitable patriotism"?

Nowhere in the archives could I find an expression of principles or sentiment by J.P. Morgan to suggest that he was trying to save the system because the free market is good or because capitalism is better than the alternative economic systems. But we can say that Morgan had lived through perhaps half a dozen anguishing financial crises and that he understood the extraordinary disruptions panics could cause. Morgan devoted his career to developing the industrial base of the United States and felt that destabilizing forces should be fought in order to sustain this legacy. And he felt a great sense of duty to the backers who supported this extraordinary episode of growth.

Is Warren Buffet the new "Jupiter" of Wall Street, as Morgan was called?

It's an appropriate comparison and yet there are big differences. The points of similarity are obvious: two very bright individuals, widely respected, able to mobilize large sums of money on short notice. But Morgan was an anchor of the East Coast establishment and Warren Buffet rather recoils from that role. He likes living in Omaha, and he shuns some folkways of the East Coast elite.

In 1907, was the average American fonder of the Wall Street titans than "Joe Six-Pack" is today?

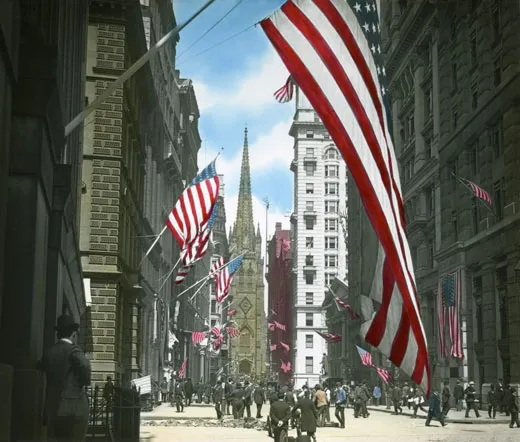

No. There was a growing distrust among average Americans toward the financial community in 1907—this reflected the extensive social changes in America. The Gilded Age spawned the age of Progressivism. Progressives gained traction because the incredible industrial expansion of the Gilded Age carried with it rising economic inequality, major societal changes (such as urbanization and industrialization), and shifts in political power. America saw the rise of movements involving worker safety and the new urban poor. Over a million people immigrated to the U.S. in 1907 alone, which was associated with urban crowding, problems of public health, and poverty. And of course the Gilded Age also produced extraordinary companies such as Standard Oil. John D. Rockefeller was the epitome of the monopolist who sought to corner industrial production in certain commodities. In 1907, Teddy Roosevelt gave two speeches that raised the level of hostility that the Progressives and the American public in general felt toward the financial community. In one speech Roosevelt referred to the "predatory man of wealth."

What reforms followed the 1907 panic?

Most importantly, it led to the founding of the U.S. Federal Reserve System. The act was passed in December of 1912, and is arguably the high water mark of the Progressive era. The panic was also associated with a change in the voting behavior of the American electorate, away from the Republicans who had dominated the post-Civil War era and toward the Democrats. Though Howard Taft was elected in 1908, Woodrow Wilson was elected in 1912, and fundamentally the Democratic Party dominated the first seven decades of the 20th century.

What reforms are we likely to see in the coming months?

I think we'll see some very pointed hearings in Congress, getting the facts, finding out what's broken down, what's happened. In the period from 1908 to 1913 there were a series of Congressional hearings that explored whether there was a money trust on Wall Street, and whether the leaders on Wall Street had triggered the panic out of their own self-interest. We may see the same starting in 2009.

If the next few years mirror past crises, we should not be surprised to see new legislationthat consolidates oversight of the financial industry within one agency or at least a much smaller set of regulators. We are likely to see legislation requiring greater transparency and heightened levels of reporting on the status and soundness of financial institutions. We're almost certain to see limits on CEO pay and benefits for corporate leaders. We may even go so far as to see a new Bretton Woods type of meeting that would the restructure multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which were founded in 1944 and have since waned somewhat in their capacity to manage global crises.

How long will it take for investors to get their confidence back this time?

The actual panic will end with a comprehensive restoration of liquidity and lender confidence. Confidence could return in a matter of weeks. The Panic of 1907 ended in the first week of January of 1908. That was a period of about 90 days. But the recession that the panic triggered continued to worsen until June of 1908 and it wasn't until early 1910 that the economy recovered to a level of the activity it enjoyed before the onset.

Panics can be short lived but devastating in their collateral damage on the economy. What we don't know this very day is which companies are laying off workers or delaying or canceling investments, or which consumers are not planning to build houses or buy cars or even have children because of these difficulties. It is the impact on the "real" economy that we should fear. I believe the government and the major institutions ultimately will prevail. But it's the collateral damage that could take a year or 18 months or 24 months to recover.

Did you anticipate the modern crisis when writing the book?

We had no premonition that there would be a panic this year but we could say with confidence that there would be a crisis someday, because crises are commonplace in market economies.

We should manage our affairs as individuals and corporations and governments to anticipate these episodes of instability.