If one were to pinpoint the precise moment the Porter sisters experienced the pinnacle of literary fame, it would likely be the year 1814. By then, Jane and Anna Maria Porter were in their late 30s and living together outside London. They’d published 17 books, including several international bestsellers, and gained reputations as two very different paragons of feminine talent. Jane’s looks and personality proved a tall, dark and serious contrast to Maria’s, as light, bright and sparkling. With no more than a charity-school education, the sisters had grown up nurturing each other’s ambitions, editing each other’s writing and turning themselves into household names.

The Misses Porter (as they were sometimes called) arguably created the modern historical novel, weaving fascinating, romantic tales out of facts and events culled from history books. The sisters were certainly the first to achieve critical acclaim and bestseller status with such novels, starting with Jane’s Thaddeus of Warsaw (1803), Maria’s The Hungarian Brothers (1807) and Jane’s The Scottish Chiefs (1810). Their protagonists—a mix of historical figures and invented characters—participated in bloody conflicts on past battlefields, then faced domestic hardships at home and abroad. Both sisters used compelling flourishes, and an undercurrent of clear moralism, to bring history’s heroes and despots to life.

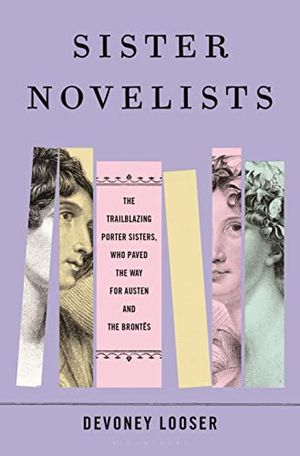

Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës

A fascinating, insightful biography of the most famous sister novelists before the Brontës

It’s no accident that Jane and Maria made these contributions to literature during the Napoleonic Wars, when the threat loomed of a despot’s global domination. Their novels about liberty and independence, set in threatened nations of decades and centuries past, couldn’t help but shed light on the situation near at hand. Indeed, Napoleon himself understood the dangers the sisters’ books posed to him: He banned Jane’s novels from publication in France, presumably because they might encourage popular uprisings. The narrator of Thaddeus of Warsaw describes the hero’s thinking in a way no tyrant would have approved of: “He well knew the difference between a defender of his own country and the invader of another’s.”

When Jane died in 1850, she was called “one of the most distinguished novelists which England has produced” and “the first who introduced that beautiful kind of fiction, the historical romance.” The Porter sisters’ careers ended just as the Brontë sisters were getting started in the early Victorian period. And over the next century, as the Brontës became literary history’s most visible sisters, the Porters were gradually—and then almost entirely—forgotten.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/2b/332b1c94-c5c1-4f3b-a0f1-e35c3082b705/jp_harlowe_2_dkl_coll_copy.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/07/00/070036e8-e082-4dbe-872c-51bfb346859f/jp_harlowe_2_dkl_coll_copy.png)

Back in 1814, no one could have predicted that the Porter sisters’ fame was about to begin its slow fade to black. Maria’s The Recluse of Norway was one of the more memorable of the 65 novels published in Britain that year, alongside titles by such popular novelists as Frances Burney and Maria Edgeworth. It’s possible the Porter sisters didn’t understand they were witnessing a literary turning point: After all, the two novels that would become 1814’s most enduring works were by authors then either unknown or underappreciated.

One was Jane Austen, whose third novel, Mansfield Park, failed to attract reviews and sold poorly. Its fame came much later. The other was Waverley; or ’Tis Sixty Years Since, which became an immediate bestseller. Set during the 1745 Jacobite rising, in which supporters of Prince Charles Edward Stuart sought to secure the throne for his father, the son of deposed king James II, Waverley was a work of historical fiction of the type the Porter sisters had pioneered. Its mysterious author came to be called “the Great Unknown.” From the first, however, many readers—including Austen—correctly guessed it was by renowned Scottish poet Sir Walter Scott. (The Porter sisters weren’t so sure.)

Austen even complained, privately and jokingly, about Scott’s entry into the world of novel-writing, which she considered her territory. As she wrote to her niece Anna, “Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones.—It is not fair.—He has fame & profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking the bread out of other people’s mouths.—I do not like him, & do not mean to like Waverley if I can help it—but I fear I must.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/89/e6/89e6277f-eb3d-42a9-a50e-5b9fb9d41309/jane.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/3c/cd3c3568-fd50-4672-9e8f-89743ba28e56/scott.jpg)

Jane and Maria were initially skeptical that Waverley had come from Scott’s pen. They’d known him as children growing up in Edinburgh and may well have believed that if Waverley were really Scott’s creation, then surely their old acquaintance would have credited their fiction as an inspiration. Yet “the Great Unknown” never did so, privately or publicly. Waverley’s long postscript named Edgeworth and several other writers as having inspired his fiction, but the Porter sisters went unmentioned. The author also claimed he’d begun Waverley about the year 1805 and then set it aside. That narrative conveniently placed Waverley’s origins before most of the Porter sisters’ historical novels.

Scott’s failure to acknowledge any debt to the famous Porters naturally left the sisters hurt and angry, and it must have struck many readers as strange. By 1814, any regular reader would have thought it obvious that Scott was following in the sisters’ footsteps. Scott would go on to publish two dozen similar titles, collectively referred to as the “Waverley novels,” and would veil his identity as author for another decade and a half, still without crediting the Porters. By the 1820s, Scott had begun to overshadow Jane and Maria in output and reputation. The origins of the historical novel were becoming obscured.

Despite these circumstances, the Porter sisters were, as usual, busy writing. Maria’s The Recluse of Norway, her 11th book, had been rushed to completion in 1814, since the sisters were struggling for money. Mercifully, it did well enough: The novel was republished in America and translated into French; it earned a second British edition by 1816. Reviews were nevertheless mixed. The most glowing one came from what might today seem a surprising source: Maria’s sister, Jane. Jane had accepted an invitation from the editor of the Augustan Review to submit a customary unsigned review of The Recluse. Safe under the cover of anonymity, Jane went beyond praise of her sister’s book to trace the arc of the novel from what was considered a lowly genre into a high art form. This change had happened over the course of a century, Jane wrote, in large part thanks to women writers.

The ascension of the novel, Jane argued, “will be found in the late elevation of the female sex, who form at once its most delightful subjects and its ablest votaries.” Jane indulged, too, in a little secret self-congratulation: “Among the female novelists, there is, perhaps, none who more strikingly proves the truth of these observations, than the lady before us [Anna Maria Porter], or her sister.” In this hidden act of self-praise, Jane wasn’t exaggerating her prominence. But she didn’t grasp how quickly the phenomenon she was describing would change after the success of Scott’s Waverley. The Waverley novels flipped the narrative about men’s versus women’s capacity for producing great fiction writing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/ae/c0ae9d32-411a-44fc-9441-f8a23cc20826/img_0420.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5e/a7/5ea7492f-1476-4d7a-abf8-752c3f5d275b/scottish-chiefs.jpg)

Scott hadn’t played any part in the Porters’ lives after their childhood. In the 30 years since he had been friends with the sisters, he’d married and had children and was working as a lawyer and sheriff in Edinburgh. He’d published historical romances in verse that sold brilliantly and became the most popular poet in Britain. Indeed, even before the Porters understood that Scott was the author of Waverley, they saw traces of their own fictional methods in his historical verse, and it rubbed them the wrong way.

“Borrowing,” Jane had once privately called it. Maria used a stronger word—“theft.” One of Scott’s poems, The Vision of Don Roderick (1811), parlayed the same historical material about conflicts in Portugal that Maria had used in her novel Don Sebastian (1809). Another of Scott’s poems, Lord of the Isles (1815), seemed to pick up where Jane’s The Scottish Chiefs had left off. By April 1815, Jane had become privately irate. She complained to Maria that Scott and Robert Southey, then the poet laureate of Great Britain, were doing for verse what the sisters had done for fiction. Each man seemed to be lifting his characters from their novels, commenting on current events through historical material and enlivening it all with domestic romance. “It is monstrous how these poets play the vampire with our works,” Jane wrote to Maria. “Some time or other, I think I shall be provoked to give the public the real Genealogy of these matters.”

The circumstances that provoked Jane’s ire in the spring of 1815 have been hidden away for almost 200 years, in the sisters’ thousands of still-unpublished private letters. (A handful of scholars have tried to piece together what exactly happened, using the sisters’ massive correspondence, much of which is now housed in libraries in California, Kansas and New York.) It’s clear that Jane’s anger arose because, two weeks earlier, she’d been reunited with Scott for the first time since their youth. After hearing Scott was staying in London, she sought him out. The idea of renewing their acquaintance must have seemed obvious—at least to Jane. He was a famous poet. She was a famous novelist. Their families had once known each other.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/0c/7c0ccd42-ec57-4d9f-80bd-53fb4027d760/amp_color_dkl_coll_copy.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2b/38/2b381695-4ad4-4c6d-bf75-d55792301bda/jane2.jpg)

“I knew him instantly at the door he was coming out of,” Jane wrote to her sister in April 1815. “His picture, but more the face as I had remembered it in Scotland, assured me it was him. He kindly expressed much pleasure in seeing me. I was in Mrs. Patterson’s carriage; & tomorrow I call on his wife.” That week, Jane visited the Scotts more than once. She found Mrs. Scott pleasing and animated. She liked Scott, too, although she thought he lacked a degree of grace and frankness. “In short,” Jane wrote, “he looks like a man, who could play the literary part, he has done to me.”

Maria hoped Scott would make things right. She replied, “I doubt not, now he has seen you, he will repent his literary sins against you.” Borrowing, theft or vampirism—these were the “literary parts” that Jane believed Scott had played, and Maria clearly considered them a sin. The sisters may have hoped Scott would express a debt of gratitude for the inspirations he’d found in their novels. Even a private compliment or two would likely have sufficed as penance, but a public acknowledgment would have been more welcome—and more powerful.

The Porter sisters weren’t unrealistic. They knew the literary marketplace thrived on imitation and recycling. It didn’t seem to bother them unduly, as long as author-borrowers made gracious acknowledgments and the imitations didn’t hamper their own reputations. But in the end, no such acknowledgment came from Scott, and the sisters’ reputations suffered materially as a result. Jane was later told by the physician Sir Andrew Halliday that Scott, when put on the spot, had admitted Jane’s role in inspiring Waverley. It reportedly happened in a conversation before George IV, no less. But Scott never went on the record to give the sisters the credit that could have secured their enduring place in literary history.

Eventually, Jane took her case to the public, but not until more than 12 years after Waverley’s publication. She first detailed her complaint in 1827, under the initials “J. P.,” in a short story titled “Nobody’s Journal.” Writing in character as Nobody, Jane sarcastically argued that Nobody had published historical fiction before Scott. In 1831, she dropped the cloak of anonymity and signed an essay asserting, in her own voice, that Scott “did me the honour to adopt the style or class of novel of which Thaddeus of Warsaw was the first.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/4b/8f4b4d56-5d2b-4579-b831-069c5b198dc4/img-0419_orig.jpeg)

Her claim prompted sexist cruelty and outright ridicule, as the literary elite lined up behind Scott. One of Scott’s camp mocked her in the pages of the Aberdeen magazine, writing, “Let us hope that the world will now do justice to you—that Sir Walter Scott will be ignominiously deprived of his laurels, while Miss Jane Porter will float down to posterity … when Homer, Shakespeare, Scott … are all buried in dusky oblivion!”

The following year, Jane buried her beloved sister Maria, who died after a brief illness in June 1832. Three months later, Scott died, too, deep in debt. His supporters began a fundraising campaign to preserve Abbotsford, his grand estate, with its extensive library and large collection of antiquities, for the good of the nation. Jane—broke, homeless and staying in friends’ spare bedrooms—was invited to contribute. Although she had practically nothing, she scraped together £5 so as not to appear stingy to the powerful men who’d asked her to give. She arranged for her publisher to sign the public donation book on her behalf, without naming the amount, saying the contribution was a small tribute to his memory from the Porters, the friends of his youth.

In the 1840s, in Jane’s old age, Scott’s admirers erected a remarkable tower to memorialize him in Edinburgh. It still stands as one of the world’s largest literary monuments. After Jane died, never having owned a home of her own, her family’s private papers were sold at auction for a pittance and squirreled away by a notorious manuscript hoarder. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the hoarder’s heirs returned his massive collection, bit by bit, to the auction houses, including the Porter papers.

Jane and Maria’s fascinating letters, and the secrets they contain, came to be divided among dozens of libraries across the globe. Most ended up in the United States, which is in some ways fitting, because Jane’s novels sold at least a million copies in America before her death. That transatlantic export of the Porters’ unpublished papers may also explain why their first full-length biography, Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës, is being published in the United States by an American biographer. The lives and careers of these wrongly forgotten sister novelists have been freshly reconstructed from the archives, two centuries after their fall from fame. Once again, the public will have the chance to restore to the Porter sisters the literary credit they enjoyed, however briefly, and which has long been their due.

Excerpted from Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës by Devoney Looser. Published by Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2022 by Devoney Looser. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(673x467:674x468)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/75/0b/750b7c43-63e4-45be-8302-1552159646bb/porter2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/devoney2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/devoney2.png)