The Fox Sisters and the Rap on Spiritualism

Their seances with the departed launched a mass religious movement—and then one of them confessed that “it was common delusion”

![]()

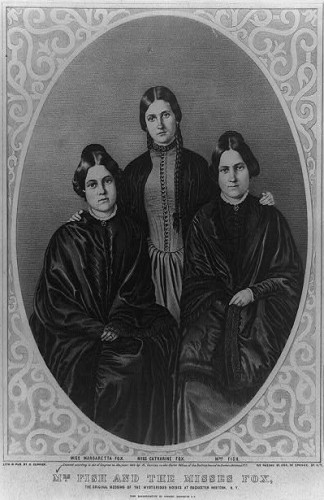

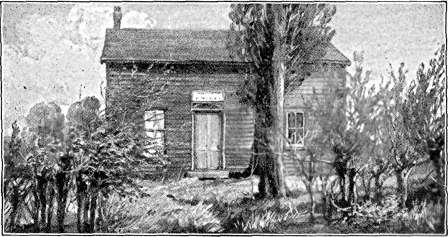

One of the greatest religious movements of the 19th century began in the bedroom of two young girls living in a farmhouse in Hydesville, New York. On a late March day in 1848, Margaretta “Maggie” Fox, 14, and Kate, her 11-year-old sister, waylaid a neighbor, eager to share an odd and frightening phenomenon. Every night around bedtime, they said, they heard a series of raps on the walls and furniture—raps that seemed to manifest with a peculiar, otherworldly intelligence. The neighbor, skeptical, came to see for herself, joining the girls in the small chamber they shared with their parents. While Maggie and Kate huddled together on their bed, their mother, Margaret, began the demonstration.

“Now count five,” she ordered, and the room shook with the sound of five heavy thuds.

“Count fifteen,” she commanded, and the mysterious presence obeyed. Next, she asked it to tell the neighbor’s age; thirty-three distinct raps followed.

“If you are an injured spirit,” she continued, “manifest it by three raps.”

And it did.

Margaret Fox did not seem to consider the date, March 31—April Fool’s Eve—and the possibility that her daughters were frightened not by an unseen presence but by the expected success of their prank.

The Fox family deserted the house and sent Maggie and Kate to live with their older sister, Leah Fox Fish, in Rochester. The story might have died there were it not for the fact that Rochester was a hotbed for reform and religious activity; the same vicinity, the Finger Lakes region of New York State, gave birth to both Mormonism and Millerism, the precursor to Seventh Day Adventism. Community leaders Isaac and Amy Post were intrigued by the Fox sisters’ story, and by the subsequent rumor that the spirit likely belonged to a peddler who had been murdered in the farmhouse five years beforehand. A group of Rochester residents examined the cellar of the Fox’s home, uncovering strands of hair and what appeared to be bone fragments.

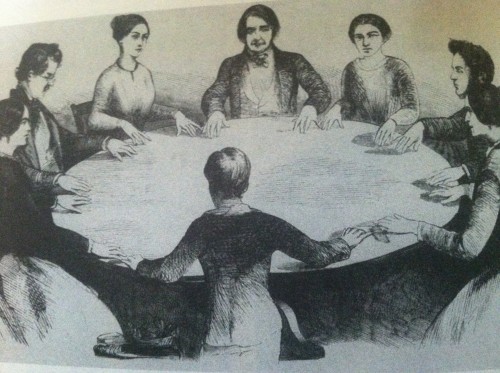

The Posts invited the girls to a gathering at their home, anxious to see if they could communicate with spirits in another locale. “I suppose I went with as much unbelief as Thomas felt when he was introduced to Jesus after he had ascended,” Isaac Post wrote, but he was swayed by “very distinct thumps under the floor… and several apparent answers.” He was further convinced when Leah Fox also proved to be a medium, communicating with the Posts’ recently deceased daughter. The Posts rented the largest hall in Rochester, and four hundred people came to hear the mysterious noises. Afterward Amy Post accompanied the sisters to a private chamber, where they disrobed and were examined by a committee of skeptics, who found no evidence of a hoax.

The idea that one could communicate with spirits was hardly new—the Bible contains hundreds of references to angels administering to man—but the movement known as Modern Spiritualism sprang from several distinct revolutionary philosophies and characters. The ideas and practices of Franz Anton Mesmer, an 18th-century Australian healer, had spread to the United States and by the 1840s held the country in thrall. Mesmer proposed that everything in the universe, including the human body, was governed by a “magnetic fluid” that could become imbalanced, causing illness. By waving his hands over a patient’s body, he induced a “mesmerized” hypnotic state that allowed him to manipulate the magnetic force and restore health. Amateur mesmerists became a popular attraction at parties and in parlors, a few proving skillful enough to attract paying customers. Some who awakened from a mesmeric trance claimed to have experienced visions of spirits from another dimension.

At the same time the ideas of Emanuel Swedenborg, an 18th-century Swedish philosopher and mystic, also surged in popularity. Swedenborg described an afterlife consisting of three heavens, three hells and an interim destination—the world of the spirits—where everyone went immediately upon dying, and which was more or less similar to what they were accustomed to on earth. Self love drove one toward the varying degrees of hell; love for others elevated one to the heavens. “The Lord casts no one into hell,” he wrote, “but those who are there have deliberately cast themselves into it, and keep themselves there.” He claimed to have seen and talked with spirits on all of the planes.

Seventy-five years later, the 19th-century American seer Andrew Jackson Davis, who would become known as the “John the Baptist of Modern Spiritualism,” combined these two ideologies, claiming that Swedenborg’s spirit spoke to him during a series of mesmeric trances. Davis recorded the content of these messages and in 1847 published them in a voluminous tome titled The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind. “It is a truth,” he asserted, predicting the rise of Spiritualism, “that spirits commune with one another while one is in the body and the other in the higher spheres…all the world will hail with delight the ushering in of that era when the interiors of men will be opened, and the spiritual communication will be established.” Davis believed his prediction materialized a year later, on the very day the Fox sisters first channeled spirits in their bedroom. “About daylight this morning,” he confided to his diary, “a warm breathing passed over my face and I heard a voice, tender and strong, saying ‘Brother, the good work has begun—behold, a living demonstration is born.’”

Upon hearing of the Rochester incident, Davis invited the Fox sisters to his home in New York City to witness their medium capabilities for himself. Joining his cause with the sisters’ ghostly manifestations elevated his stature from obscure prophet to recognized leader of a mass movement, one that appealed to increasing numbers of Americans inclined to reject the gloomy Calvinistic doctrine of predestination and embrace the reform-minded optimism of the mid-19th century. Unlike their Christian contemporaries, Americans who adopted Spiritualism believed they had a hand in their own salvation, and direct communication with those who had passed offered insight into the ultimate fate of their own souls.

Maggie, Kate, and Leah Fox embarked on a professional tour to spread word of the spirits, booking a suite, fittingly, at Barnum’s Hotel on the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane, an establishment owned by a cousin of the famed showman. An editorial in the Scientific American scoffed at their arrival, calling the girls the “Spiritual Knockers from Rochester.” They conducted their sessions in the hotel’s parlor, inviting as many as thirty attendees to gather around a large table at the hours of 10 a.m., 5 p.m. and 8 p.m., taking an occasional private meeting in between. Admission was one dollar, and visitors included preeminent members of New York Society: Horace Greeley, the iconoclastic and influential editor of the New York Tribune; James Fenimore Cooper; editor and poet William Cullen Bryant, and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who witnessed a session in which the spirits rapped in time to a popular song and spelled out a message: “Spiritualism will work miracles in the cause of reform.”

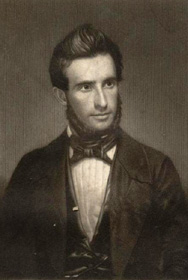

Leah stayed in New York, entertaining callers in a séance room, while Kate and Maggie took the show to other cities, among them Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, St. Louis, Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia, where one visitor, explorer Elisha Kent Kane, succumbed to Maggie’s charms even as he deemed her a fraud—although he couldn’t prove how the sounds were made. “After a whole month’s trial I could make nothing of them,” he confessed. “Therefore they are a great mystery.” He courted Maggie, thirteen years his junior, and encouraged her to give up her “life of dreary sameness and suspected deceit.” She acquiesced, retiring to attend school at Kane’s behest and expense, and married him shortly before his untimely death in 1857. To honor his memory she converted to Catholicism, as Kane—a Presbyterian—had always encouraged. (He seemed to think the faith’s ornate iconography and sense of mystery would appeal to her.) In mourning, she began drinking heavily and vowed to keep her promise to Kane to “wholly and forever abandon Spiritualism.”

Kate, meanwhile, married a devout Spiritualist and continued to develop her medium powers, translating spirit messages in astonishing and unprecedented ways: communicating two messages simultaneously, writing one while speaking the other; transcribing messages in reverse script; utilizing blank cards upon which words seemed to spontaneously appear. During sessions with a wealthy banker, Charles Livermore, she summoned both the man’s deceased wife and the ghost of Benjamin Franklin, who announced his identity by writing his name on a card. Her business boomed during and after the Civil War, as increasing numbers of the bereaved found solace in Spiritualism. Prominent Spiritualist Emma Hardinge wrote that the war added two million new believers to the movement, and by the 1880s there were an estimated eight million Spiritualists in the United States and Europe. These new practitioners, seduced by the flamboyance of the Gilded Age, expected miracles—like Kate’s summoning of full-fledged apparitions—at every séance. It was wearying, both to the movement and to Kate herself, and she, too, began to drink.

On October 21, 1888, the New York World published an interview with Maggie Fox in anticipation of her appearance that evening at the New York Academy of Music, where she would publicly denounce Spiritualism. She was paid $1,500 for the exclusive. Her main motivation, however, was rage at her sister Leah and other leading Spiritualists, who had publicly chastised Kate for her drinking and accused her of being unable to care for her two young children. Kate planned to be in the audience when Maggie gave her speech, lending her tacit support.

“My sister Katie and myself were very young children when this horrible deception began,” Maggie said. “At night when we went to bed, we used to tie an apple on a string and move the string up and down, causing the apple to bump on the floor, or we would drop the apple on the floor, making a strange noise every time it would rebound.” The sisters graduated from apple dropping to manipulating their knuckles, joints and toes to make rapping sounds. “A great many people when they hear the rapping imagine at once that the spirits are touching them,” she explained. “It is a very common delusion. Some very wealthy people came to see me some years ago when I lived in Forty-second Street and I did some rappings for them. I made the spirit rap on the chair and one of the ladies cried out: ‘I feel the spirit tapping me on the shoulder.’ Of course that was pure imagination.”

She offered a demonstration, removing her shoe and placing her right foot upon a wooden stool. The room fell silent and still, and was rewarded with a number of short little raps. “There stood a black-robed, sharp-faced widow,” the New York Herald reported, “working her big toe and solemnly declaring that it was in this way she created the excitement that has driven so many persons to suicide or insanity. One moment it was ludicrous, the next it was weird.” Maggie insisted that her sister Leah knew that the rappings were fake all along and greedily exploited her younger sisters. Before exiting the stage she thanked God that she was able to expose Spiritualism.

The mainstream press called the incident “a death blow” to the movement, and Spiritualists quickly took sides. Shortly after Maggie’s confession the spirit of Samuel B. Brittan, former publisher of the Spiritual Telegraph, appeared during a séance to offer a sympathetic opinion. Although Maggie was an authentic medium, he acknowledged, “the band of spirits attending during the early part of her career” had been usurped by “other unseen intelligences, who are not scrupulous in their dealings with humanity.” Other (living) Spiritualists charged that Maggie’s change of heart was wholly mercenary; since she had failed to make a living as a medium, she sought to profit by becoming one of Spiritualism’s fiercest critics.

Whatever her motive, Maggie recanted her confession one year later, insisting that her spirit guides had beseeched her to do so. Her reversal prompted more disgust from devoted Spiritualists, many of whom failed to recognize her at a subsequent debate at the Manhattan Liberal Club. There, under the pseudonym Mrs. Spencer, Maggie revealed several tricks of the profession, including the way mediums wrote messages on blank slates by using their teeth or feet. She never reconciled with sister Leah, who died in 1890. Kate died two years later while on a drinking spree. Maggie passed away eight months later, in March 1893. That year Spiritualists formed the National Spiritualist Association, which today is known as the National Spiritualist Association of Churches.

In 1904, schoolchildren playing in the sisters’ childhood home in Hydesville—known locally as “the spook house”—discovered the majority of a skeleton between the earth and crumbling cedar walls. A doctor was consulted, who estimated that the bones were about fifty years old, giving credence to the sisters’ tale of spiritual messages from a murdered peddler. But not everyone was convinced. The New York Times reported that the bones had created “a stir amusingly disproportioned to any necessary significance of the discovery,” and suggested that the sisters had merely been clever enough to exploit a local mystery. Even if the bones were that of the murdered peddler, the Times concluded, “there will still remain that dreadful confession about the clicking joints, which reduces the whole case to a farce.”

Five years later, another doctor examined the skeleton and determined that it was made up of “only a few ribs with odds and ends of bones and among them a superabundance of some and a deficiency of others. Among them also were some chicken bones.” He also reported a rumor that a man living near the spook house had planted the bones as a practical joke, but was much too ashamed to come clean.

Sources:

Books: Barbara Weisberg, Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rose of Spiritualism. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2004; Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth Century America. Boston: Beacon University Press, 1989; Nancy Rubin Stuart, The Reluctant Spiritualist: The Life of Maggie Fox. Orlando, Fl: Harcourt, 2005; Reuben Briggs Davenport, The Death-Blow to Spiritualism. New York: G.W. Dillingham, 1888; Andrew Jackson Davis, The Principles of Nature, Her Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind. New York: S.S. Lyon and William Fishbough, 1847.

Articles: “The Origin of Spiritualism.” Springfield Republican, June 20, 1899; “Gotham Gossip. Margaretta Fox Kane’s Threatened Exposure of Spiritualism.” New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 7, 1888; “Fox Sisters to Expose Spiritualism.” New York Herald Tribune, October 17, 1888; “The Rochester Rappings.” Macon Telegraph, May 22, 1886; “Spiritualism Exposed.” Wheeling (WVa) Register, October 22, 1888; “Spiritualism in America.” New Orleans Times- Picayune, April 21, 1892; “Spiritualism’s Downfall.” New York Herald, October 22, 1888; “Find Skeleton in Home of the Fox Sisters.” Salt Lake Telegram, November 28, 1904; Joe Nickell, “A Skeleton’s Tale: The Origins of Modern Spiritualism”: http://www.csicop.org/si/show/skeletons_tale_the_origins_of_modern_spiritualism/.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)