The Glory That Is Rome

Thanks to renovations of its classical venues, the Eternal City has never looked better

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Roman-Colosseum-facade-631.jpg)

Climbing the Campidoglio, or Capitoline Hill, which has lured visitors to Rome since the days of the Caesars, still provides the best, most inspiring introduction to this dynamic city. This was the most sacred of antiquity’s seven hills, and in the Imperial Age (27 B.C.-A.D. 476) the Temple of Jupiter graced its summit. One of the travelers who made a pilgrimage to this spot over the centuries was the young Edward Gibbon, who, on an autumnal evening visit in 1764, was shocked by how little survived from Imperial Rome. Surveying the melancholy ruins “while the bare-footed fryars were singing Vespers,” he was then and there inspired to write his monumental history, The Declineand Fall of the Roman Empire.

In his masterwork, Gibbon took as his starting point Rome at the height of its glory, in the second century A.D., when the Capitoline Hill was a symbol of the city’s eternal power and the Temple of Jupiter a stunning sight. Beneath the temple’s gold-plated roof, an immense gold-and-ivory statue of the king of the Roman gods presided over artworks from around the known world. But it was the spectacular view that hypnotized. From the Campidoglio’s exalted heights, ancient travelers gazed at a rich urban tapestry below. Rome was the largest metropolis the world had ever seen, and its marble structures, the Greek orator Aelius Aristides observed around A.D. 160, covered the horizon like snow.

Today, the Campidoglio is dominated by the renovated Capitoline Museums, twin Renaissance palaces facing a piazza designed by Michelangelo. The oldest public museums in the world, their gleaming hallways are lined with classical masterpieces such as the Etruscan bronze She-Wolf suckling the twins Romulus and Remus, the symbol of the city, and the marble Dying Gaul and Capitoline Venus. And while the Temple of Jupiter was razed by looters in the fifth and sixth centuries A.D., its site has once again become an imperative destination for Italians—as the EternalCity’s most spectacular outdoor café. Standing on its rooftop terrace and gazing across Rome’s fabled red-tiled roofs at sunset, foreigners and locals alike congratulate themselves on being in the most beautiful metropolis on earth—just as they did 2,000 years ago. “Rome in her greatness!” wrote the poet Propertius in the age of Augustus Caesar. “Stranger, look your fill!”

A new spirit is alive in all the classical venues of Rome, once notorious for their apathetic staff, erratic schedules and lack of display labels. Some favorites had been closed for decades; even at the Capitoline, visitors never knew which rooms would be open or what exhibits buried in storage. Now Roman museums are among the most elegantly designed and its archaeological sites the most user-friendly in the world. “Compared to Rome in the mid-1980s, the improvement is incredible,” says archaeologist Nicola Laneri, 35. “And there is another big change: it’s not just foreign tourists who are taking advantage of the cultural improvements. A huge number of Italians are now visiting them.”

In fact, Rome is enjoying a new age of archaeology—the third in the city’s modern history. The first occurred in the 1870s when Rome became the capital of a newly unified Italy and King Victor Emmanuel II ordered the Colosseum and Forum cleared of rubble. Then in the 1920s and ’30s, Mussolini tore up much of central Rome and exposed the port of Ostia, the city’s main seaport in antiquity, as part of his campaign to gain popular support for his misguided ventures (although he destroyed almost as much as he saved). The current, more scientific effort began in the 1990s, powered by funds to spruce up the city for the Grand Jubilee millennial festivities in the year 2000. Not only did the jubilee put unprecedented millions of dollars into renovations, but it sparked contentious municipal, national and Vatican bureaucracies to complete several long-dormant projects. “The jubilee was a huge catalyst for change in Rome,” says Diane Favro, professor of architecture at UCLA, who is working with University of Virginia professor Bernard Frischer to create an interactive digital model of the Roman Forum that will allow a virtual walk-through of the site. “Paired with the digital revolution, there’s been a huge leap forward in our understanding of the ancient city.”

Although arguments over funding of the sites continue unabated, the resurgence of interest in the ancient past shows little sign of waning. Last month Italian officials unveiled a magnificent 28-foot-high sacrificial altar dedicated by the emperor Augustus in 9 B.C. to celebrate the advent of the Pax Romana. (Called the Ara Pacis, or Altar of Peace, the famous monument, first excavated in the early 20th century and later restored by Mussolini’s archaeologists, has been under a protective covering for six years while a new museum pavilion to hold it, designed by American architect Richard Meier, was under construction. The pavilion, with exhibits, a library and an auditorium, is scheduled to open next year.) Responding to popular demand, Rome’s once-secretive Archaeological Superintendency now posts the latest discoveries on the Internet. New digs are followed closely in the Italian press and discussed avidly in cafés.

All this renewed fervor has historical symmetry: ancient Romans were also passionate admirers of their own city, says Favro, and they joined hordes of provincial tourists trooping from one monument to the next.

In fact, Imperial Rome was designed specifically to impress both its citizens and visitors: the first emperor, Augustus (27 B.C.-A.D. 14), began an ambitious beautification program, which led to one glorious edifice after another rising above the confusing welter of tenements. It was under Augustus that Rome first began to look like a world capital: its splendid monuments hewn from richly colored marble were, Pliny the Elder wrote in A.D. 70, “the most beautiful buildings the world has ever seen.” With the completion of the Colosseum in A.D. 80 and Emperor Trajan’s massive Forum in A.D. 113, the image of Rome we carry today was virtually complete. With more than one million inhabitants, the megalopolis had become the greatest marvel of antiquity: “Goddess of continents and peoples, Oh Rome, whom nothing can equal or even approach!” gushed the poet Martial in the early second century A.D.

In 1930, Sigmund Freud famously compared modern Rome to the human mind, where many levels of memory can coexist in the same physical space. It’s a concept those classical sightseers would have understood: the ancient Romans had a refined sense of genius loci, or spirit of place, and saw Rome’s streets as a great repository of history, where past and present blurred. Today, we can feel a similarly vivid sense of historical continuity, as the city’s rejuvenated sites use every conceivable means to bring the past to life.

Imaginative links to history are everywhere. The ancient Appian Way, Rome’s Queen of Highways south of the city, has been turned into a ten-mile-long archaeological park best reconnoitered by bicycle. The roadside views have hardly changed since antiquity, with farmland still filled with sheep as well as the mausoleums of Roman nobles, which once bore epitaphs such as “I advise you to enjoy life more than I did” and “Beware of doctors: they were the ones who killed me.”

Back in the city’s historical center, the Colosseum—still the marquee symbol of the Imperial Age—has had part of its surviving outer wall cleaned, and a number of subterranean passages used by gladiators and wild beasts have been revealed to the public. (For ancient tourists as well, a visit here was de rigueur, to see criminals being torn to pieces or crucified in the morning, then, after a break for lunch, men butchering one another in the afternoon; chariot races in the Circus Maximus rounded out the entertainments.) The vast cupola of the Pantheon, at 142 feet once the largest in Western Europe, is undergoing restoration. And the Domus Aurea, Emperor Nero’s Golden House, was reopened with great fanfare in 1999 after a ten-year renovation. Visitors can now rent “video-guides”—palm pilots that show close-ups of the ceiling frescoes and computer re-creations of several rooms. Thanks to these, standing inside the dark interior of the palace, which was buried in the first century A.D., one can envision the walls as Nero saw them, encrusted with jewels and mother-of-pearl, surrounded by fountains and with tame wild animals prowling the gardens.

In antiquity, Rome’s most opulent monuments were part of the urban fabric, with residences squeezed onto the flanks of even the sacred Campidoglio; it was Mussolini who isolated the ancient ruins from the neighborhoods around them. Today, urban planners want to restore the crush. “Rome is not a museum,” declares archaeologist Nicola Laneri. “Florence is more like that. It’s the people that make Rome. It’s the depth of history within individual lives.”

The Roman Forum has been opened to the public free of charge, returning to its ancient role as the city’s original piazza: today, Romans and tourists alike stroll through its venerable stones again, picnicking on mozzarella panini near the ruins of the Senate House or daydreaming by a shrine once tended by Vestal Virgins. Afew blocks away, the Markets of Trajan, created in the second century A.D. as a multistory shopping mall, now doubles as a gallery space for contemporary art. In a maze of vaulted arcades, where vendors once hawked Arabian spices and pearls from the Red Sea, and where fish were kept fresh swimming in salt water pumped from the coast ten miles away, the shops are filled with metal sculptures, video installations and mannequins flaunting the latest designer fashions.

Every Sunday, the strategic Via dei Fori Imperiali, which runs alongside the Imperial Forums toward the Colosseum, is blocked to motor vehicles—so pedestrians no longer have to dodge buses and dueling Vespas. The modern thoroughfare has been problematic ever since it was blasted through the heart of Rome by the Fascist government in the 1930s, leveling a hill and wiping out an entire Renaissance neighborhood. Mussolini saw himself as a “New Augustus” reviving the glories of the ancient empire, and he wanted direct sightlines from the Piazza Venezia, where he gave his speeches, to the great Imperial icons. In July 2004, the Archaeology Superintendency released a proposal to build walkways over the Imperial Forums, allowing Romans to reclaim the area. While the vaguely sci-fi design has its critics—and the project has gone no further than the drawing board—many city citizens feel that something must be done to repair Mussolini’s misanthropy.

“It’s really Rome’s age-old challenge: How do you balance the needs of the modern city with its historical identity?” says Paolo Liverani, curator of antiquities at the VaticanMuseum. “We cannot destroy the relics of ancient Rome, but we cannot mummify the modern city, either. The balancing act may be impossible, but we must try! We have no choice.”

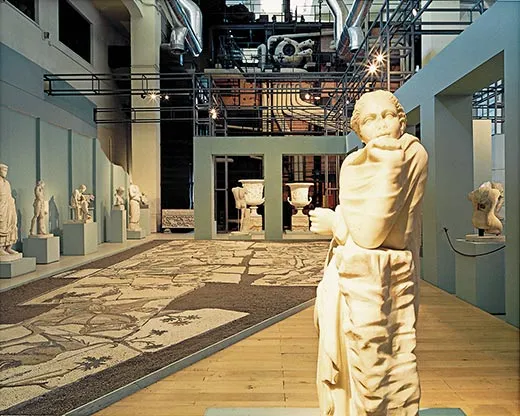

One effective bit of balancing took place at the MontemartiniMuseum, where sensuous marble figures are juxtaposed with soaring metal turbines in an abandoned 19th century electrical plant. Opened in 1997, the exhibition was originally meant to be temporary, but it proved so popular that it was made permanent. Other attempts to mix modern and classical have been less universally admired. Richard Meier’s museum to house the Ara Pacis is the most controversial. The first new edifice in Rome’s historical center since the days of Mussolini, it has been roundly criticized for its starkly angular travertine-and-glass design, which many Romans feel violates the ambiance of the old city. In one notorious attack, Vittorio Sgarbi, undersecretary to the Ministry of Culture, compared the museum’s boxlike form to a “gas station in Dallas” and set the building afire in effigy; other Meier critics have lamented the “Los Angelization of Rome.”

Of course, it’s not just architects who are mixing past and present. As one example, the Gruppo Storico Romano, or Roman Historical Group, lures everyone from bank clerks to

truck drivers to its school for gladiators on the Appian Way. Even visiting the school’s headquarters tests one’s nerves. Behind a corrugated iron fence in a dimly lit courtyard, half-adozen students don tunics and helmets and grab sinister-looking props such as tridents and daggers. The teacher, Carmelo Canzaro, 36, runs a clothing store by day, but becomes Spiculus when the sun sets. “There’s nothing in the ancient texts that describe gladiators’ training techniques,” he admits, “so we have to improvise.” As the students—all male—begin to swing and parry with wooden swords, “Spiculus” adds: “You have to pay complete attention. One lapse and you can be caught off balance.” (He himself was sitting the evening out, recovering from a broken ankle incurred at a recent demonstration bout.)

During a rest period, a young computer programmer, Massimo Carnevali, 26, a.k.a. Kyros, explains the school’s appeal. “It combines history with physical exercise,” he says. “I love the discipline.” Another student, Ryan Andes, 26, an opera singer from Philadelphia, says, “To come here and chop at people with swords was a dream come true.”

Edward Gibbon understood that appeal. Although he was no fan of gladiatorial combat—he found the practice “inhumane” and “horrid”—he would always remember the impression his first visit to Rome made on his youthful imagination. As he wrote in his autobiography: “At the distance of twenty-five years, I can neither forget nor express the strong emotions which agitated my mind as I first approached and entered the eternal city. After a sleepless night, I trod, with a lofty step, the ruins of the Forum; each memorable spot where Romulus stood, or Tully spoke, or Caesar fell, was at once present to my eye, and several days of intoxication were lost or enjoyed before I could descend to a cool and minute investigation.”

HBO’S ROME

Despite its grandiose monuments, most of Imperial Rome was a squalid maze jammed with crumbling tenement houses lining ten-foot alleys filled with tradesmen, vendors and pedestrians as well as the occasional falling brick or the contents of a chamber pot. Jugs of wine hung from tavern doors. The street noise was deafening. (“Show me the room that lets you sleep!” observed the satirist Juvenal. “Insomnia causes most deaths here.”) Rich and poor were squeezed together, along with immigrants from every corner of the empire—professors from Greece, courtesans from Parthia (modern Iraq), slaves from Dacia (Romania) and boxers from Aethiopia. Animal trainers, acrobats, fire-eaters, actors and storytellers filled the forums. (“Give me a copper,” went a refrain, “and I’ll tell you a golden story.”)

On my last day in Rome, I explored the urban depths: I lurched through the dismal Subura, a slum neighborhood where Romans lived in cramped, windowless rooms with no running water, and I peered into one of their unisex latrines, where they wiped themselves with a communal sponge. Around one corner, I stumbled onto a makeshift arena, where a fight was in progress: 400 Romans in tattered, grimy tunics howled with laughter as mangled corpses were dumped on carts and limbs lay about in pools of blood. A dog dashed in to grab a severed hand.

Soon, during a lull in the mayhem, a svelte, Gucci-clad Italian woman tottered across the bloody sand in stilettos, to touch up the makeup of one of the extras. This was Cinecittà, the sprawling film studio on the outskirts of Rome that some call the world.s greatest factory for images of ancient life. Such classics as Quo Vadis, Ben-Hur and Cleopatra were all shot here, as well as Fellini’s Satyricon.

HBO is filming its $100 million series “Rome” (which began airing August 28) on a five-acre set that re-creates the city in the last days of the Republic. Bruno Heller, the show’s cocreator, hopes that the series will do for antiquity what HBO’s 2004 “Deadwood” did for the Old West: demythologize it.

“It’s sometimes hard for us to believe that the ancient Romans really existed in the quotidian sense,” Heller said, as we strolled back lots filled with period uniforms and props. “But they were real, visceral, passionate people.” The series attempts to show the Romans without judging them by modern, Christian morality. “Certain things are repressed in our own culture, like the open enjoyment of others’ pain, the desire to make people submit to your will, the guilt-free use of slaves,” Heller added. “This was all quite normal to the Romans.” —T.P.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)