The Goddess Goes Home

Following years of haggling over its provenance, a celebrated statue once identified as Aphrodite, has returned to Italy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Goddess-statue-main-631.jpg)

From the look on Renzo Canavesi’s face, our first encounter was not going to end well. The strapping, barrel-chested octogenarian stared down at me from the second-floor landing of his home in the foothills of the Swiss Alps while a dog barked wildly from behind an iron gate. I had traveled more than 6,000 miles to ask Canavesi about one of the world’s most contested pieces of ancient art: a 2,400-year-old statue of a woman believed to be Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love.

The statue, which stands seven-and-a-half-feet tall and weighs more than half a ton, had reigned since 1988 as the centerpiece of the Greek and Roman antiquities collection at the J. Paul Getty Museum near Malibu, California, the world’s richest art institution. Italian officials insisted it had been looted from central Sicily, and they wanted it back. Canavesi had been identified as the statue’s previous owner. When I knocked on his door that day five years ago, I was a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and he was living quietly in the town of Sagno, just north of the border with Italy.

“It’s too delicate of an issue,” he called down to me. “I don’t want to say anything to anyone.”

When I persisted, his face darkened and he threatened to call the police. “Mind your own business....I’m not saying another word,” he said, and slammed the door behind him. But by then, the goddess had become everybody’s business—the most visible symbol of an escalating contest of wills between elite American art museums and Old World cultural officials.

For decades, U.S. museums, and private collectors who donated objects to them, had been purchasing antiquities at auction or from dealers. With objects of unclear provenance, or ownership history, an attitude of don’t tell, don’t ask prevailed: sellers offered scant, dubious or even false information. Museums and other buyers commonly accepted that information at face value, more concerned that the objects were authentic than how they came to market. Foreign cultural officials occasionally pressed claims that various vases, sculptures and frescoes in U.S. museum showcases had been looted—stripped from ancient ruins and taken out of archaeological context—and smuggled out of their countries, in violation of both foreign patrimony laws and an international accord that sought to end illicit trafficking in cultural property. Museums resisted those claims, demanding evidence that the contested artifacts had indeed been spirited away.

The evidence, when it was produced, brought about an unprecedented wave of repatriations—not only by the Getty, but also by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Princeton University Art Museum, as well as from antiquities dealers and collectors.

Within the past five years, museums have returned to the Italian and Greek governments more than 100 artifacts worth nearly $1 billion. The Met gave back 21 pieces, including its celebrated Euphronios krater, a Greek vessel dating to about 515 B.C., which the museum had acquired in 1972 for a then-record $1 million. The Boston MFA returned 13 objects, including a statue of Sabina, wife of the second-century A.D. Roman emperor Hadrian. In no case did a museum acknowledge wrongdoing on its part, and, in a historic shift, the Italian government agreed to make long-term loans of other antiquities to take the place of those that had been repatriated.

The Getty gave back more objects than any other museum—47, nearly a dozen of them masterpieces—and the last piece to go was its iconic goddess. The story of the statue stands as a case study of how longstanding practices in the market for Greek and Roman antiquities were overtaken by changes in attitude, the law and law enforcement.

Throughout a modern odyssey covering more than 30 years, the Getty’s goddess had cast a spell over those who possessed her, those who desired her and those who simply tried to understand her. During six years of reporting and writing about the Getty with Times reporter Jason Felch, first for the newspaper and then a book, we buttonholed investigators, lawyers, cultural officials, museum administrators, curators, tomb raiders and one purported smuggler with suspected Mafia ties. And still I couldn’t let go. So this past May, Jason and I found ourselves on an airplane, heading to Italy once again, to see the goddess in her new home.

The plundering of artifacts goes back millennia. An Egyptian papyrus from 1100 B.C. describes the prosecution of several men caught raiding a pharaoh’s tomb. The Romans looted the Greeks; the Visigoths pillaged Rome; the Spanish sacked the Americas. Napoleon’s army stripped Egypt of mummies and artifacts, followed by professional treasure hunters like the Great Belzoni, who took to the pyramids with battering rams. England’s aristocracy stocked its salons with artifacts lifted from archaeological sites during the “grand tours” that were once de rigueur for scions of wealth. Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin, loaded up on so many marble sculptures from the Parthenon that he scandalized members of Parliament and drew poison from Lord Byron’s pen.

The so-called Elgin marbles and other harvests gravitated into the collections of state-run institutions—“universal museums,” as they were conceived during the Enlightenment, whose goal was to exhibit the range of human culture under one roof. Filled with artworks appropriated in the heyday of colonialism, the Louvre and the British Museum—home of Elgin’s Parthenon sculptures since 1816—said they were obeying an imperative to save ancient artifacts from the vagaries of human affairs and preserve their beauty for posterity. (Their intellectual descendants, such as New York’s Met, would echo that rationale.) To a large degree, they succeeded.

Attitudes began changing after World War I, when plundered patrimony began to be seen less as a right of victors than as a scourge of vandals. Efforts to crack down on such trafficking culminated in a 1970 accord under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco). The agreement recognized a country’s right to protect and control artifacts within its borders and called on nations to block the illicit trade in antiquities through import and export restrictions.

Museum and cultural officials worldwide hailed the agreement, but some of the nations with the hottest markets were among the slowest to ratify it. The United States did so in 1983; Switzerland, a notorious hub of the trade, followed suit in 2003. Meanwhile, dealers kept offering unprovenanced artifacts, and many curators and collectors kept buying. None shopped harder than the Getty.

Opened in 1954 by the oil baron J. Paul Getty, the museum was initially a boutique collection of 18th-century French furniture, tapestries, old master paintings and classical artifacts. Then in 1976, Getty died and left the institution the bulk of his $700 million fortune. Soon it became a giant, with ambitions to compete with older museums. It focused first on building its antiquities collection.

The museum immediately paid nearly $4 million for a sublime Greek bronze statue believed to be the last surviving work of Lysippos, master sculptor for Alexander the Great. (The work is no longer attributed to him.) It acquired $16 million worth of antiquities from the New York diamond merchant Maurice Tempelsman. It spent $9.5 million for a rare kouros, or ancient statue of a Greek youth, that many experts now believe is fake. This buying spree climaxed in 1988, when Getty officials announced they had acquired a towering statue of a Greek goddess from the fifth century B.C.

An unknown sculptor had caught the female figure in midstride, with her right arm extended and her gown rippling in the wind, as if she were walking through a storm. The statue’s size and detail suggested the goddess had been the object of cult worship in an ancient temple. Its rare combination of materials—head and extremities of fine marble, body of limestone—distinguished it as an acrolithic statue, a kind of amalgam, or artistic scarecrow, created where marble was scarce. The wet-drapery style of its dress placed its creation during the height of Greek classicism, shortly after Phidias chiseled the Parthenon statuary that would so enthrall the Earl of Elgin.

The statue bore few clues to the figure’s identity. Its head was a bit small. Something had been torn from its right hand, which ended at broken knuckles. But based on its drapery and voluptuous figure, Marion True, who had become the Getty’s antiquities curator in 1986, concluded that the figure was likely Aphrodite. In her pre-purchase curator’s report to the museum board, True made clear that acquiring the statue would be a coup, even with its then-record $18 million price tag. “The proposed statue of Aphrodite would not only become the single greatest piece of ancient art in our collection,” she wrote, “it would be the greatest piece of Classical sculpture in this country and any country outside of Greece and Great Britain.”

Yet the statue had appeared out of nowhere, unknown to leading antiquities experts. The London dealer who offered it to the Getty provided no documentation of its provenance and would say only that its prior owner had been a collector in a Swiss town just north of Italy. The museum’s Rome attorney told the Italian Ministry of Culture “an important foreign institution” was considering buying the statue and asked if it had any information on the piece; the answer was no. Among the outside experts consulted by True, two raised questions about the statue’s legitimacy. One of them, Iris Love, an American archaeologist and friend of True’s, said she told True: “I beg you, don’t buy it. You will only have troubles and problems.” [In a written statement to Smithsonian, True said Love was shown photographs of the statue but “had nothing to say herself about the possible provenance or importance of the object” and “offered no counsel about purchase.”]

The director of the Getty’s Conservation Institute, Luis Monreal, inspected the statue before the purchase was completed. He noted recent breaks in the torso—looters commonly break artifacts into pieces for easier transport—and fresh dirt in the folds of the dress. Concluding that it was a “hot potato,” he pleaded with John Walsh, the museum’s director, and Harold Williams, CEO of the Getty Trust, to reject it.

They didn’t. Critics excoriated the Getty for buying the “orphan,” as art insiders call antiquities offered for sale without provenance. Other museums had acquired smaller orphans, discreetly inserting them into their collections, but the magnitude of this acquisition riled foreign officials and archaeologists alike; they argued that the goddess had almost certainly been looted. Italian officials claimed she had been taken from an ancient site in the Sicilian town of Morgantina, once a Greek colony. Journalists descended on a sleepy excavation site there and reported that it was a favorite target of looters. The local archaeological superintendent said the Getty attorney’s request for information on the statue had never been forwarded to her. An American legal publication, the National Law Journal, ran a photograph of the artwork and a story with the headline “Was This Statue Stolen?”

Around the same time, a Sicilian judge accused the Getty of harboring two other looted objects on loan. The museum removed them from public view and returned them to their owners—and then put its prize statue on permanent display in early 1989. (The Getty’s purchase did not violate Unesco sanctions because Italy had not yet petitioned the State Department for cultural import restrictions, as a federal implementing law required.)

Meanwhile, the museum was growing into a cultural behemoth. The Getty Trust’s endowment, aided by the 1984 sale of Getty Oil, approached $5 billion. To its Roman villa-style museum near Malibu it added, in 1997, the Getty Center, a vast modernist complex on a hill overlooking Los Angeles’ hip Westside.

Marion True became an outspoken proponent for reform in the antiquities market, openly criticizing what she called her U.S. museum colleagues’ “distorted, patronizing and self-serving” justifications for buying suspect artifacts. She helped Cyprus officials recover four sixth-century Byzantine mosaics stolen from a church. She began to return Getty objects known to have been looted, including hundreds of pieces from the museum’s study collection—pieces of scholarly, if not aesthetic, value. By November 1995, she had pushed through a new policy committing the Getty to acquiring antiquities only from documented collections, essentially pulling the museum out of the black market. The policy was the first of its kind at a major collecting institution.

And yet True had something of a shock when she traveled to Rome in 1999 to return three looted Getty artifacts to the Italian government. She was signing the paperwork in a ceremony at Villa Giulia, the museum for Etruscan antiquities, when an Italian prosecutor named Paolo Ferri approached.

This is a very nice gesture, Ferri told the startled curator, but the Getty must do more. “Maybe next time,” he said, “you’ll bring back the Venus of Morgantina,” using the Roman name for Aphrodite.

“Maybe next time,” True replied, “you’ll have evidence it came from there.”

Much to Ferri’s frustration, the Italians had little evidence. In 1989, officials had charged several Sicilians with looting and smuggling the statue but abandoned the case because it was too weak. In 1994, Italian investigators had filed a formal legal request for a chip of limestone from the torso for analysis. When the Getty complied nearly a year later, the tests matched the limestone to a geological formation 50 miles south of Morgantina. But that alone, the museum said, “does not establish a Morgantina provenance for the piece.”

In recent years, Italy’s national art squad had shifted its focus from the bottom of the antiquities trade—the small-time diggers and moonlighting farmers—to its middlemen and their wealthy clients. In a 1995 raid on a middleman’s Geneva warehouse, they found something they’d never seen before: thousands of Polaroid photographs showing freshly excavated artifacts—broken, dirty, propped up on newspapers, lying in a car trunk. For the first time, they had grim “before” photos to contrast with glamour shots in art catalogs.

The investigators spent years painstakingly matching the Polaroids to objects on museum shelves—in Japan, Germany, Denmark and the United States. They traced them to the Met, the Boston MFA, the Cleveland Museum and elsewhere. The greatest number, nearly 40, were at the Getty, with the most recent having been acquired during True’s tenure.

In December 2004, based on the Polaroids and other evidence, Ferri won a conviction of the middleman, Giacomo Medici, for trafficking in illicit archaeological objects. It was the largest such conviction in Italian history, and it resulted in a ten-year prison sentence and $13.5 million fine. The sentence was later reduced to eight years, and the conviction is still under appeal.

The following April, Ferri secured an indictment of True as a co-conspirator with Medici and another middleman. She was ordered to stand trial in Rome. Ferri’s evidence list against True included Getty objects depicted in the Polaroids, plus one that was not: the Venus of Morgantina. He had added it at the last minute, he said, hoping to “make a bang.”

Marion True was the first curator in the United States to be accused by a foreign government of trafficking in illicit art. [In her written statement to Smithsonian, she described her indictment and trial as a “political travesty” and said, “I, not the institution, its director nor its president, was used by the Italian state as a highly visible target to create fear among American museums.”]

Jason Felch and I learned from confidential Getty documents and dozens of interviews that while True was building her reputation as a reformer, she maintained curatorial ties to suppliers of unprovenanced, and likely illicit, objects. In 1992, she agreed to meet two men at a Zurich bank to inspect a gold Greek funerary wreath from the fourth century B.C. Rattled by the encounter, True turned down the wreath, writing to the dealer who had referred her to the two sellers that “it is something that is too dangerous for us to be involved with.” [True, in her statement, wrote that she described the situation that way “not because the wreath was questionable but because it was impossible for the museum to deal with completely unreliable and seemingly capricious people.”] Four months later, the dealer offered it himself, at a price reduced from $1.6 million to $1.2 million. True recommended it and the museum bought it. The Getty would return the wreath to Greece in 2007.

Jason and I also documented that True’s superiors, who approved her purchases, knew the Getty might be buying illicit objects. Handwritten notes by John Walsh memorialized a 1987 conversation in which he and Harold Williams debated whether the museum should buy antiquities from dealers who were “liars.” At one point, Walsh’s notes quote Williams, a former Securities and Exchange Commission chairman, as saying: “Are we willing to buy stolen property for some higher aim?” Williams told us he was speaking hypothetically.

Even in 2006, some 18 years after the Getty purchased its goddess, the statue’s origins and entry into the market remained obscure. But that year a local art collector in Sicily told Jason that tomb raiders had offered him the goddess’s head, one of three found around Morgantina in 1979. According to previous Italian newspaper reports, the torso had been taken to a high place, pushed onto a blunt object and broken into three roughly equal pieces. The pieces were then loaded into a Fiat truck and covered with a mountain of loose carrots to be smuggled out of the country.

While Jason was reporting in Sicily, I went to Switzerland to interview Renzo Canavesi, who used to run a tobacco shop and cambia, or money-changing house, near Chiasso, just north of the Italian border. For decades the border region had been known for money-laundering and smuggling, mostly in cigarettes but also drugs, guns, diamonds, passports, credit cards—and art. It was there in March 1986 that the goddess statue first surfaced in the market, when Canavesi sold it for $400,000 to the London dealer who would offer it to the Getty.

The transaction had generated a receipt, a hand-printed note on Canavesi’s cambia stationery—the statue’s only shred of provenance. “I am the sole owner of this statue,” it read, “which has belonged to my family since 1939.” After the London dealer turned the receipt over to authorities in 1992, an Italian art squad investigator said he thought Canavesi’s statement was dubious: 1939 was the year Italy passed its patrimony law, making all artifacts discovered from then on property of the state. After a second lengthy investigation in Italy, Canavesi was convicted in absentia in 2001 of trafficking in looted art. But the conviction was overturned because the statute of limitations had expired.

Canavesi twice declined to talk to me, so I asked some of his relatives if they had ever noticed a giant Greek statue around the family home. A niece who had taken over Canavesi’s tobacco shop replied: “If there had been an expensive statue in my family, I wouldn’t be working here now, I’d be home with my children.” Canavesi’s younger brother, Ivo, who ran a women’s handbag business from his home down the mountain from Sagno, said he knew nothing about such a statue. “Who knows?” he said with a chuckle. “Maybe it was in the cellar, and no one spoke about it.”

By then, Jason and I were crossing paths with a law firm the Getty had hired to probe its antiquities acquisitions. Private investigators working for the firm managed to secure a meeting with Canavesi. He told them his father had bought the statue while working in a Paris watch factory, then carted it back in pieces to Switzerland, where they wound up in a basement under Canavesi’s shop. Then he showed the investigators something he had apparently shared with no previous inquisitor.

He pulled out 20 photographs of the goddess in a state of disassembly: the marble feet covered in dirt, one of them configured from pieces, on top of a wooden pallet. The limestone torso lay on a warehouse floor. A close-up showed a dirt-encrusted face. Most telling was a picture of some 30 pieces of the statue, scattered over sand and the edges of a plastic sheet.

In 1996, Canavesi had sent photocopies of two photographs to Getty officials and offered to provide fragments from the statue and discuss its provenance. True declined to talk to him, later saying she had been suspicious of his motives. Now, ten years later, the 20 photographs Canavesi showed to the investigators all but screamed that the statue had been looted. After seeing that evidence, the Getty board concluded it was no Canavesi family heirloom. In talks with the Italian Culture Ministry, the museum first sought joint title to the statue, then in November 2006 signaled that it might be willing to give it up.

By then, American museum officials, shaken by news photographs of Marion True trying to shield her face as she walked through the paparazzi outside a Rome courthouse, were making their own arrangements to return artifacts investigators had identified from Giacomo Medici’s Polaroids.

The Met made its repatriation deal with Italy in February 2006, the Boston MFA eight months later. The Princeton museum followed in October 2007 with an agreement to transfer title to eight antiquities. In November 2008, the Cleveland Museum committed to give back 13 objects. Just this past September, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts agreed to return a 2,500-year-old vase.

The Getty completed its agreement in August 2007. Previously it had returned four items, including the funerary wreath, to Greece and three to Italy. Now it agreed to return 40 more objects to Italy, the majority of which had been depicted in the Polaroids, plus the goddess. Having played hardball, the Italians relented. They allowed the Getty to keep the statue on display until December 2010.

By the time the statue left for Italy this past March, American museums and the Italian government had come to terms. Even as the museums returned contested objects, Italian officials relaxed their country’s long-standing opposition to the long-term loan of antiquities. The Getty and other museums pledged to acquire only artifacts with documented provenance before 1970, the year of the Unesco accord, or legally exported afterward.

Marion True resigned from the Getty in 2005, and her case was dismissed in October 2010, the statute of limitations having expired. Though she has largely melted into private life, she remains a subject of debate in the art world: scapegoat or participant? Tragic or duplicitous?

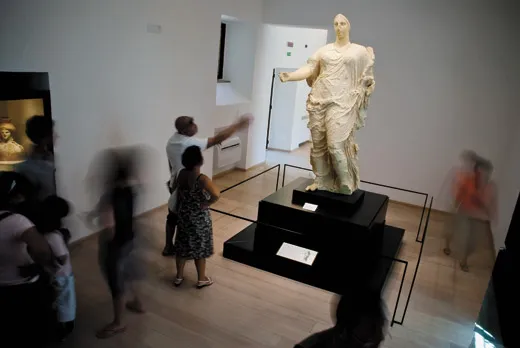

From Rome, the statue was taken to its new home, the Sicilian town of Aidone, near Morgantina. It seemed as if all 5,000 townspeople turned out to welcome it. A band played as the crates bearing the goddess’s parts were wheeled over the cobblestone streets to the town museum.

At a preview of the reassembled statue in May, a local archaeologist named Flavia Zisa wondered whether the goddess’s “new mythology”—the whodunit of how she came to rest at the Getty—had overshadowed its “old mythology,” the story of her origins and purpose.

“The ‘new mythology’ has distracted the people,” said Zisa. She said she first saw the statue in 1995, as a 32-year-old intern at the Getty Museum (where she became a protégée and friend of Marion True’s). “But no one thought of the ‘old mythology.’ We don’t even know the [goddess’s] name. We don’t even know the objects that were found next to the sculpture. We don’t know anything.” Indeed, the Aidone museum identifies the sculpture without reference to Aphrodite or Venus. Its plaque reads: “The statue of a female deity from Morgantina, excavated clandestinely and exported illegally, was repatriated in 2011 by the J. Paul Getty Museum of Malibu.”

When the statue was officially unveiled the next day, citizens, politicians and others descended on the museum. “There is a deep sense of patriotism in every one of us,” said Iana Valenti, who works as an English interpreter. “The return of this statue is very important. It is like a piece of our culture, a piece of our country.” A Getty official read a statement by David Bomford, the museum’s acting director, saying the decision to return the statue had been “fraught with much debate” but “was, without a doubt, the right decision.”

One consequence of repatriation, it seems, is that fewer people will see the statue. The Getty Villa receives more than 400,000 visitors a year; the Aidone museum is used to about 10,000. Tourism officials note that a Unesco Heritage Site 20 minutes away, the fourth-century Villa Romana del Casale outside Piazza Armerina, attracts nearly 500,000 tourists a year. There are plans to draw some of them to Aidone, but there is also a recognition that the town’s museum, a 17th-century former Capuchin monastery, accommodates only 140 people at a time. Officials plan to expand the museum and say they are improving the road between Aidone and Piazza Armerina.

Former Italian Culture Minister Francesco Rutelli says the statue’s ultimate fate rests with the people of Aidone. “If they are good enough to make better roads, restaurants,” says Rutelli, now a senator, “they have a chance to become one of the most beautiful, small and delicate cultural districts in the Mediterranean.”

After the statue’s debut, monthly museum attendance shot up tenfold. Across the town square, a gift shop was selling ashtrays, plates and other knickknacks bearing an image of the statue. Banners and T-shirts bore both a stylized version of it along with the logo of the Banco di Sicilia.

Back in the United States, I wondered what Renzo Canavesi would think of the homecoming. In one last stab at closing out the statue’s new mythology, I hunted down his telephone number and asked an Italian friend to place a call. Would he be willing to talk?

“I’m sorry, but I have nothing to say,” he answered politely. “I’m hanging up now.”

Ralph Frammolino is the co-author, with Jason Felch, of Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum. Photographer Francesco Lastrucci is based in Florence, New York City and Hong Kong.