“The Grave Looked So Miserable”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130118095131James-Idle-funeral-August-1914-web.jpg)

Picture the British countryside and the chances are that you are picturing the unmatched beauty of the Cotswolds, in England’s green heart, west of London. Picture the Cotswolds, and you have in your mind’s eye a place like Hullavington: a handful of cottages, some thatched, but all clustered around a village green, a duck pond and a church. The latter will most likely be ancient, 600 or 700 years old, and its graveyard will be filled with generation after generation of villagers, the same family names carved on tombstones that echo down the centuries even as they weather into slabs of rock.

Visit the church at Hullavington, though, and your eye will soon be drawn to one century-old grave, placed against a bank of ivy and remarkable not merely for its pristine whiteness, but also for the identity of the young man buried there. James Idle, who died a couple of miles away late in August 1914, was a soldier who had no family or friends in the village; indeed, in all likelihood he’d never even been there when he was killed guarding a railway in the very first month of the First World War. But Idle’s funeral—held a few days later in the presence of a handful of men from his regiment and a gaggle of respectful villagers—inspired a remarkable response in one girl who witnessed it. Marjorie Dolman was only 9 years old when she watched the soldier being carried to his grave; she is probably among the village girls pictured in the contemporary postcard shown above. Yet something about the funeral touched her so deeply that, from then until almost the end of her life (and she died at age 99), she made it her unbidden duty to lay fresh flowers daily on Private Idle’s grave.

“On the day of the funeral,” records her fellow villager, Dave Hunt, “she picked her first posy of chrysanthemums from her garden and placed them at the graveside. Subsequently she laid turf and planted bulbs and kept the head stone scrubbed. On Remembrance Sunday she would lay red roses.”

In time, Dolman began to think of Private Idle as her own “little soldier”; as a teenager, she came to see it as her duty to tend a grave that would otherwise have been neglected. “When the soldiers marched off,” she recalled not long before her own death, “I can remember feeling sad because the grave looked so miserable,” and even at age 9, she understood that Idle’s family and friends would not be able to visit him. The boy soldier (contemporary sources give his age as 19) came from the industrial town of Bolton, in the north of England, 150 miles away, and had they wished to make the journey, and been able to afford it, wartime restrictions on travel would have made it impossible.

“I suppose it was only a schoolgirl sweetness at the time,” reminisced Dolman, who at a conservative estimate laid flowers at the grave more than 31,000 times. “But as the years went by the feelings of grief became maternal.”

James Idle’s death took place such a long time ago, and so early in a cataclysm that would claim 16 million other lives, that it is perhaps not surprising that the exact circumstances of his death are no longer remembered in Hullavington. A little research in old newspapers, however, soon uncovers the story, which is both tragic and unusual—for Private Idle was not only one of the first British troops to die in the war; he also met his death hundreds of miles from the front line, before even being sent to France.

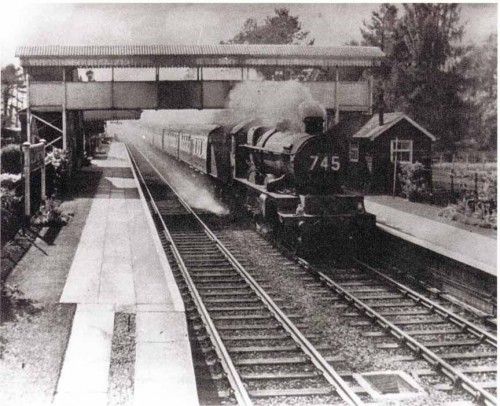

According to the Manchester Courier, published only a few miles from Idle’s Bolton home, the boy died a sadly unnecessary death, “cut to pieces by an express train…while guarding a viaduct at Rodbourne, Malmesbury,” not far from the spot where he was buried. A report of the inquest into the incident, published a few days later in the Western Daily Press, suggests his death was frankly puzzling. Another private in Idle’s regiment, the 5th Royal North Lancashire Territorials, who witnessed it, attributed the incident to the fact that “he had new boots on, and these apparently caused him to slip.” But another soldier saw things differently:

At 12.30 (mid-day), when Idle was proceeding down the line, witness saw the Bristol to London express train approaching. Idle was on the same side as the train and facing it. Witness shouted to him a warning, but instead of stepping aside Idle turned around and walked up the line. He seemed to have lost his head, for he took no notice of witness’s shouts.

Unable to solve this mystery, the coroner (that is, the medical examiner) recorded a verdict of accidental death. Further investigation, though, reveals one other oddity about the railway at the point where Idle died: a long stretch of dead-straight main line track, running through Hullavington and on for several miles, allowed expresses to reach speeds of almost 100 miles per hour, suggesting that perhaps Idle—who cannot have been familiar with the district—badly underestimated how rapidly the train that killed him was approaching.

Whatever the truth, a death that in normal circumstances would have been swept away and soon forgotten in the maelstrom of the First World War gained a strange and enduring nobility from a young girl’s actions. Marjorie Dolman’s lifetime of devotion was eventually recognized, in 1994, when the British Army held a special service at the grave and commemorated Private Idle with full military honors. And when Marjorie herself died in 2004, she was laid to rest only a few yards from her little soldier, in the same churchyard that she had visited daily since August 1914.

Sources

‘Territorial killed on the railway.’ Western Daily Press, August 28, 1914; ‘Three territorials dead.’ Manchester Courier, August 28, 1914; ‘Territorial’s sad death.’ Western Daily Press, August 31, 1914; Dave Hunt. ‘Private J. Idle and a visit to the Somme Battlefields.’ Hullavington Village Website, nd (c. 2007); Richard Savill. ‘Girl’s lifetime of devotion to “little soldier.”‘ Daily Telegraph . December 6, 2004.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)