The Indian Guru Who Brought Eastern Spirituality to the West

A new biography explores the life of Vivekananda, a Hindu ascetic who promoted a more inclusive vision of religion

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b8/1a/b81a06e8-db67-4546-af24-8f273c7221b4/vadenandaka.jpg)

One morning in September 1893, a 30-year-old Indian man sat on a curb on Chicago’s Dearborn Street wearing an orange turban and a rumpled scarlet robe. He had come to the United States to speak at the Parliament of the World’s Religions, part of the famous World Columbian Exposition. The trouble was, he hadn’t actually been invited. Now he was spending nights in a boxcar and days wandering around a foreign city. Unknown in America, the young Hindu man, named Vivekananda, was a revered spiritual teacher back home. By the time he left Chicago, he had accomplished his mission: to present Indian culture as broader, deeper and more sophisticated than anyone in the U.S. realized.

Every American and European who dabbles in meditation or yoga today owes something to Vivekananda. Before his arrival in Chicago, no Indian guru had enjoyed a global platform quite like a world’s fair. Americans largely saw India as an exotic corner of the British Empire, filled with tigers and idol worshippers. The Parliament of the World’s Religions was meant to be a showcase for Protestantism, particularly mainline groups like Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists and Episcopalians.

So the audience was astonished when Vivekananda, a representative of the world’s oldest religion, seemed anything but primitive—the highly educated son of an attorney in Calcutta’s high court who spoke elegant English. He presented a paternal, all-inclusive vision of India that made America seem young and provincial.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a9/54/a954a671-df9a-400c-94dd-ffcab8d87ab8/swami_vivekananda_at_parliament_of_religions.jpeg)

“I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance,” he declared on September 11, 1893. “We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true. I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth. I am proud to tell you that we have gathered in our bosom the purest remnant of the Israelites, who came to Southern India and took refuge with us in the very year in which their holy temple was shattered to pieces by Roman tyranny. I am proud to belong to the religion which has sheltered and is still fostering the remnant of the grand Zoroastrian nation.”

Vivekananda was well-equipped to bridge cultural divides. As a young man named Narendranath Datta, he’d attended Christian schools where he’d been steeped in the Bible and European philosophy. According to one story, his introduction to Indian spirituality came by way of a lecture on English romantic literature. A professor, a Scottish clergyman, mentioned the ecstasies of a nearby guru called Ramakrishna during a discussion of transcendental experiences in William Wordsworth’s poem “The Excursion.” The students ended up paying Ramakrishna a visit, and Datta went on to embrace Ramakrishna as his guru and adopt a renunciate’s name, Vivekananda, which meant “the bliss of gaining wisdom.”

Now, in Chicago, Vivekananda’s words were warm and inviting, but they were also the words of an activist. That same year, Mohandas Gandhi had arrived in South Africa, where he upended the social order by walking on whites-only paths and refusing to leave first-class railroad cars. Vivekananda likewise wanted to show the world that Indians would no longer be demeaned and defined by European occupiers. He found sympathetic audiences in America, a country that liked to think of itself as anti-colonialist (even as it was on the verge of annexing Hawaii and the Philippines).

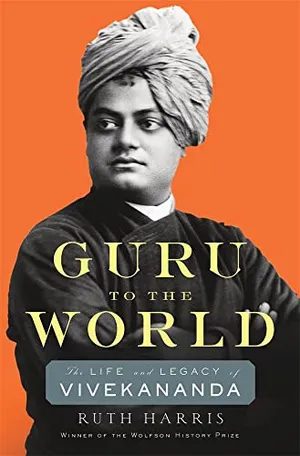

Guru to the World: The Life and Legacy of Vivekananda

From the Wolfson History Prize–winning author of The Man on Devil’s Island, the definitive biography of Vivekananda, the Indian monk who shaped the intellectual and spiritual history of both East and West.

After speaking to the crowd in Chicago, Vivekananda traveled to Detroit, Boston and New York; he met people who’d been exploring new belief systems, including Christian Science. Many of his listeners were women who applauded his message that the divine was present in every human being, transcending gender and social status. Sarah Ellen Waldo, a relative of Ralph Waldo Emerson, later recalled the experience of strolling through Manhattan with Vivekananda by her side: “It required no little courage to walk up Broadway beside that flaming coat. As the Swami strode along in lordly indifference, with me just behind, half out of breath, every eye was turned on us.” Another female enthusiast was invigorated by “the air of freedom that blew through the room” when Vivekananda debated the president of Smith College. The woman’s father disapproved of her interest in the Indian guru, but when a new calf was born to her family, she defiantly named it “Veda” (after the Hindu scriptures of the same name).

Vivekananda spent many of his remaining years traveling around the U.S. and Europe. He died of mysterious causes in 1902, at the age of 39. But generations of Indian gurus who traveled to the West went on to follow his highly successful approach, whether visiting British spiritualist societies or lecturing to middle-aged audiences in Los Angeles living rooms. In the 1960s, the Beatles launched a more youthful wave of interest when they visited India. But the underlying message of teachers from the East has changed little since Vivekananda’s first visit: The individual is cosmic, and meditation and yoga are universal tools for experiencing that underlying reality, compatible with any culture or religion.

Such stories and insights about Vivekananda’s life come alive in Guru to the World, a rich and insightful new biography by Ruth Harris, a historian at the University of Oxford’s All Souls College. Smithsonian spoke to Harris about Vivekananda’s travels through the West and how they gave rise to a kind of Eastern spirituality that most Westerners would recognize today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4b/fa/4bfa1c99-2158-4ef5-ab19-edb902ce7f82/swami_vivekananda-1893-09-signed.jpeg)

Reading your book made me think about my own upbringing. I was raised Jewish and had a bat mitzvah and all, but my parents learned Transcendental Meditation when they were in their 20s, and I grew up in a community where everyone meditated.

That is so Vivekananda. You meditated, but you went to synagogue and you were still Jewish. Vivekananda knew he couldn’t compete with the conventional churches, and at the same time, he also understood that you cannot coerce people to experience God in a way that is not their own.

What was the goal of the Columbian Exposition’s Parliament of the World’s Religions?

The organizers are really thinking that they’re going to export what they call Protestant modernism to the rest of the world. Even though there are tons of Americans evangelizing all over the world, the Protestant organizers want to convey the idea that their version of religion is anti-colonial, that they’ve been doing comparative religion at the University of Chicago and Protestant Christianity just happens to be at the top of the hierarchy. Then this Indian newcomer comes along—this extraordinary Bengali, speaking beautiful English, with an incredible intellect—and he says, “No, that‘s not the case.”

It’s interesting that Vivekananda was much worldlier and more educated than a lot of the people he met in America.

There are moments when he’s in New England when he thinks, “Oh my God, I’m in a very provincial world.” Because he’s used to Calcutta, which is the capital of the Raj, and it’s multicultural, and there are people from all over. He’s used to real diversity. There are Sikhs and Muslims and this and that. But what I think is so remarkable about him is that he doesn’t disdain these provincial Americans. He watches all this stuff they’re doing—mind control, hypnosis—and in his letters he does make fun of them, but in a very kind way. He’s also stunned by them because they are so honest, so open, so interested in learning. He’s never seen anything like it. It’s also the first time in his life he’s in mixed-sex company outside his family.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6e/2e/6e2e755d-657f-4ca0-a11e-5cbc98d25e64/1893parliament.jpeg)

How did his arrival fit into the explosion of religions and philosophies that was happening in America around that time?

By the time he arrives, many of the Americans already have a tradition of transcendentalism that they get from [Henry David] Thoreau and all these people. There’s something about what he says that’s kind of familiar. He’s very good. He knows the Bible pretty much by heart. He’s gone to a Scottish missionary school. And they’re stunned by him because he’s so culturally ambidextrous. Whereas they don’t know anything about India, and they think he’s a heathen. He comes back and he says, “I’m no heathen. I have a much more complicated and rarified metaphysical system than you. And also I can argue on your terms.”

So he does. From the beginning, he goes to different churches and he says, “I’m going to throw in another element into this bubbling world of American religion.” Mostly it’s in the Protestant sphere. Every single one of his major devotees has experimented with Christian Science, which is the major new religion founded by Mary Baker Eddy. It’s a woman’s religion; it says we’re going to have healing right now. And mind control and healing become a bridge into yoga.

Did Vivekananda know much about Emerson and Thoreau when he came to Massachusetts?

He certainly knew about Emerson. He knew about Emerson’s idea of the Over-Soul [an immortal, interconnected level of the self]. He’d read all about this in Calcutta. He also knew [Baruch] Spinoza, and he read a lot of Scottish philosophy. It’s not clear how deeply he knew all of this, but it enabled him to say things like, “We have been Spinozists for 2,000 years. You think you started everything; no, we started everything.”

There’s an element of truth in it, but it’s also very defensive. It’s a wounded commentary. Because after all, he’s a colonial subject, and he has to keep on asserting the value of India and Indians against this barrage of Western views of Indians as slothful—perhaps metaphysical, but nihilistic, inactive. He has to produce an image and a persona that counteracts those negative stereotypes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/58/0e/580e1376-8f6b-46e7-ac62-c83052bf2dd0/ramakrishna.jpeg)

Vivekananda’s guru, Ramakrishna, came from a poorer, more traditionally religious background, right?

Yes, even though [philosopher] William James and others later quoted Ramakrishna’s sayings, we don’t really know what Ramakrishna actually said, because his ideas were collected by his literate disciples. We get some sense of Ramakrishna as an incredibly charismatic, illiterate man who refuses education for many reasons, mostly because he thinks that books get in the way of true spirituality. But in Vivekananda, he picks a disciple who is the ultimate opposite.

Did Vivekananda see himself as promoting the Hindu religion?

If you go through what he talks about during the world parliament in 1893, he never talks about Hindu gods because he’s so afraid of being accused of idolatry. What he says is that even in India, people who bow down to statues have a vision of the ultimate [level of existence] behind it, and that you should stop making fun of them and being contemptuous. He emphasizes this idea that there is an ultimate cosmic unity, and you reach that through a series of disciplines and relationships and learning.

He saw Indian spirituality as an anti-colonial weapon—the goal was to make Westerners milder and more thoughtful and less brutal and less rigid. It was a gift that he wanted to bring, what he saw as a superior spirituality, because Westerners were materialistic. They didn’t know how to reach higher states of consciousness.

It doesn’t sound like God was the main thing he cared about.

That’s right. He says, “I’m not here to convert.” They find that astonishing. Though what’s interesting is when he goes to Rome, he loves the saints’ cults and the glitter and the baroque and everything. So the women ask him, “But how can you like this?” He just does his Vivekananda thing. He looks at them and says, “If you’re going to have a personal God, give it your all.” What he’s trying to say is, "I’m here in Rome."

When in Rome …

Exactly. And also he’s trying to say, “West, come and do that with us.” When he first comes to New England, he says, “I know you think that you don’t have any images, but when you pray, don’t you envisage the cross?” And they’d never thought of that. Also, he believes that Jesus is an avatar, a god-man.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/62/e6/62e6b4fb-e0b1-41d7-9869-5583ef221d33/swami_vivekananda_at_mead_sisters_house_south_pasadena.jpeg)

But above that is advaita, the unity which is formless. The reason he prioritizes the formless is because the rest of it is all symbolic. Whereas the formless—the reason why he thinks that’s so great is, you don’t fight over whether you take the Eucharist. So you’re quite right, he doesn’t talk about the Hindu gods. But when he has close devotees, he starts to talk about them.

You write about how a lot of his followers were women.

Yes, and when the women are alone with him, he chants and he cooks for them, and he has a kind of warmth and femininity and maternal qualities that they find really entrancing. They’ve never had a man cook for them before.

There’s a passage where you describe Vivekananda talking about the tradition of suttee, where a widow was expected to throw herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. He said, essentially, that if it was really their choice, they should be allowed to do it.

Vivekananda was not in favor of suttee, though his mentioning of “consent” by these women suggests that he was defensive about Western criticism of what was considered Hindu “barbarism.” I have to say, his disciple Margaret Noble, who was known as Nivedita, was much more into it than he was. She romanticized the idea of the sacrifice, especially for love and union—but I don’t think she would have liked the reality. The notion of sacrifice became very important to militant nationalism, hence her emphasis on it. This is an aspect of Hinduism that is just very hard for us to understand.

How is it different from the way we talk about sacrifice in Western religions?

In the monotheistic religions, we understand the sacrificial, too—the Abrahamic possible sacrifice of Isaac and of course Jesus’ sacrifice. But that’s not quite the same thing as the Indian idea. For instance, people think Gandhi was just like a Quaker. He was not. He believed that you should lay down your life. Your life was the only thing you had to give. The rest of what you possessed was nothing. That’s a very radical idea.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/64/cc/64cca159-87af-4a14-a070-c3effc3379f8/blessings_to_nivedita.jpeg)

What Vivekananda really didn’t like about Christianity was the notion of duty, because he thought it meant that you were constantly berating yourself. There’s a notion of Hindu dharma that is sometimes translated as “duty,” but it really has no equivalent in English. Dharma is different for different castes. It’s different for different groups. Duty is something you do for God, or to earn a place in heaven. Whereas dharma isn’t something you do to please God. It’s for yourself. The whole ethical system is altered by that.

The caste system is a topic where, even now, a lot of spiritually minded Westerners will come across a mention of it in the Bhagavad-Gita [a 700-verse dialogue about the nature of reality that is one of the core Hindu texts] and think, “I’ll pretend I didn’t see that.”

For the Indians, there was the difficulty of trying to translate. But on the other side, there’s the postmodernist American Western view that we can pick and choose, and the integrity of all these religious systems goes out the window. Then spirituality becomes a form of consumerism.

Integrity is a good word for it, but where did Vivekananda draw the line? Does integrity mean you have to accept the notion that some people are born into a lower caste and that’s just where they have to stay?

That’s what’s so moving about him. He’s constantly grappling with that himself. He hates child marriage. He doesn’t want suttee anymore; he thinks it’s terrible. He doesn’t reject caste, but he thinks you can become a caste—that people can move and recreate themselves. Yet at the same time, he fights and fights and fights with his own conscience, and with the pace of change, and what can be done in India, and what can be done in the West.

That’s what’s so hard. If you’re a guru, you’re meant to be spiritual all the time. So what do you do with all these things that are embarrassing, fear-creating, disturbing? And how do you actually examine your own culture? Are you locked into an essentialist notion, that you’re spiritual and the West is material, or you’re intuitive and the West is rational? The “East” is a geographical imaginary anyway, isn’t it? But for many of us in Europe and America, the spirituality of our grandparents’ generation no longer feels suitable for us. So we like this idea of “going to the East,” in a way where we can pick and choose.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/8f/2e8fca43-2c68-4829-a7ef-c097d3834099/gettyimages-845719664.jpg)

The way you talk about Vivekananda makes me think of other teachers from very old traditions who want to make their messages universal. The Dalai Lama can talk in such a relatable way but, at the same time, he’s the head of an actual religious group with its own rituals and beliefs.

One of the things I argue in the book is that Vivekananda was constantly ill, and we don’t know why he was so ill. You don’t want to have retrospective diagnoses and do any of that. But there is something about the strain of constantly operating on other people’s terms. He did it, but it was exhausting and very depleting—constantly being on your toes to convince people of what might be useful to them, and at the same time trying to gauge what they might be able to accept and what they might not be able to accept.

But on some level—I mean I’m joking, but honestly, we’re all Hindus now. You’re an example of how successful that was. I was at a seminar in Oxford where they were doing all this “JewBu” stuff, with Buddhism in synagogues. This is why the issue of appropriation is so complex. Because Vivekananda was really glad that Westerners were appropriating his teachings. He didn’t like the cherry-picking, but he liked different kinds of synthesis. So it’s very tricky, isn’t it?

You write about how today’s Hindu nationalists embrace Vivekananda even though his ideology was actually really different from theirs.

It’s not that you won’t find statements from Vivekananda that seem to assert Hindu superiority. But what I find amazing, when you see the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his nationalistic embrace of Vivekananda, is that you also have so many Indians who were communists, socialists—and they get it from Vivekananda.

Vivekananda died so young, but you could see his views changing with time. We are all provisional.

How did your views change during the decade you were working on this book?

I spent three or four years in turmoil because I couldn’t understand Vivekananda’s world. That’s when I started to listen to the Bhagavad-Gita, and I found Indian friends who were willing to talk to me. Now I still don’t know much, but at least I feel I’ve scratched the surface.

Above all, I realized I wasn’t afraid to actually put my cards on the table and say that what’s important in this history is spiritual love affairs. This is a book about love—the love between Vivekananda and Ramakrishna, and the love between Vivekananda and his followers in the West. Vivekananda would constantly say that devotion to the guru should not be personal. It expresses itself in personal ways, but the guru is a channel to the divine. But you just have to accept that without the love that goes on between these people, none of it is comprehensible.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.