The Invisible Line Between Black and White

Vanderbilt professor Daniel Sharfstein discusses the history of the imprecise definition of race in America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/sharfstein-oberlin-rescuers-cuyahoga-county-jail-631.jpg)

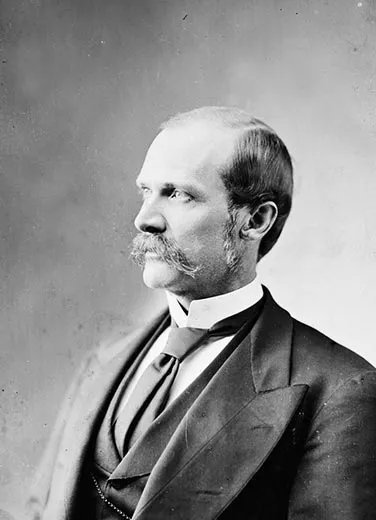

For much of their history, Americans dealt with racial differences by drawing a strict line between white people and black people. But Daniel J. Sharfstein, an associate professor of law at Vanderbilt University, notes that even while racial categories were rigidly defined, they were also flexibly understood—and the color line was more porous than it might seem. His new book, The Invisible Line: Three American Families and the Secret Journey from Black to White, traces the experience of three families—the Gibsons, the Spencers and the Walls—beginning in the 17th century. Smithsonian magazine's T.A. Frail spoke with Sharfstein about his new book:

People might assume that those who crossed the line from black to white had to cover their tracks pretty thoroughly, which would certainly complicate any research into their backgrounds. But does that assumption hold?

That’s the typical account of passing for white—that it involved wholesale masquerade. But what I found was, plenty of people became recognized as white in areas where their families were well known and had lived for generations, and many could cross the line even when they looked different. Many Southern communities accepted individuals even when they knew those individuals were racially ambiguous—and that happened even while those communities supported slavery, segregation and very hard-line definitions of race.

So how did you find the three families you wrote about?

It was a long process. I began by trying to find as many of these families as I could in the historical record. That involved reading a lot of histories and memoirs, and then moving from there to dozens and dozens of court cases where courts had to determine whether people were black or white, and from there to property records and census records and draft records and newspaper accounts. And I developed a list of dozens, even hundreds of families that I could be writing about, and then narrowed it down. The three families that I chose represent the diversity of this process of crossing the color line and assimilating into white communities. I chose families that lived in different parts of the South that became white at different points in American history and from different social positions.

And how did those families come to know about their ancestry?

For many generations, members of these three families tried to forget that they had ever been African-American—and yet when I traced the families to the present and began contacting the descendants almost everyone I contacted knew about their history. It seems that the secrets of many generations are no match for the Internet. In many families, people would talk about going to the library and seeing that it had, say, a searchable 1850 census. One woman described the experience of typing in her great-grandfather’s name, finding him, and then having to call over the librarian to go through the handwritten enumeration form with her—she had to ask the librarian what “MUL” meant, not knowing it meant he was mulatto, or of mixed race. Every family seemed to have a story like this.

You note that an early 18th-century governor of South Carolina granted the Gibsons, who clearly had African-American ancestry, permission to stay in his colony because “they are not Negroes nor Slaves.” How did the governor reach such a nebulous conclusion?

It shows how fluid understandings of race can be. The Gibsons were descended from some of the first free people of color in Virginia, and like many people of color in the early 18th century they left Virginia and moved to North Carolina and then to South Carolina, where there was more available land and the conditions of the frontier made it friendlier to people of color. But when they arrived in South Carolina there was a lot of anxiety about the presence of this large mixed-race family. And it seems that the governor determined that they were skilled tradesmen, that they had owned land in North Carolina and in Virginia and—I think most important—that they owned slaves. So wealth and privilege trumped race. What really mattered is that the Gibsons were planters.

And why was such flexibility necessary, both then and later?

Before the Civil War, the most important dividing line in the South was not between black and white, but between slave and free. Those categories track each other, but not perfectly, and what really mattered above all to most people when they had to make a choice was that slavery as an institution had to be preserved. But by the 19th century, there were enough people with some African ancestry who were living as respectable white people—people who owned slaves or supported slavery–that to insist on racial purity would actually disrupt the slaveholding South.

And this continued after the Civil War. With the rise of segregation in the Jim Crow era, separating the world by white and black required a renewed commitment to these absolute and hard-line understandings of race. But so many of the whites who were fighting for segregation had descended from people of color that even as laws became increasingly hard-line, there still was a tremendous reluctance to enforce them broadly.

One of your subjects, Stephen Wall, crossed from black to white to black to white again, in the early 20th century. How common was that crossing back and forth?

My sense is that this happened fairly often. There were many stories of people who, for example, were white at work and black at home. There were plenty of examples of people who moved away from their families to become white and for one reason or another decided to come home. Stephen Wall is interesting in part because at work he was always known as African-American, but eventually, at home everyone thought he was Irish.

How did that happen?

The family moved around a lot. For a while they were in Georgetown [the Washington, D.C. neighborhood], surrounded by other Irish families. Stephen Wall’s granddaughter remembered her mother telling stories that every time an African-American family moved anywhere nearby, Stephen Wall would pack the family up and find another place to live.

As you look at the United States now, would you say the color line is disappearing, or even has disappeared?

I think the idea that race is blood-borne and grounded in science still has a tremendous amount of power about how we think about ourselves. Even as we understand how much racial categories were really just a function of social pressures and political pressures and economic pressures, we still can easily think about race as a function of swabbing our cheek, looking at our DNA and seeing if we have some percentage of African DNA. I think that race has remained a potent dividing line and political tool, even in what we think of as a post-racial era. What my book really works to do is help us realize just how literally we are all related.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)