The Jetsons Get Schooled: Robot Teachers in the 21st Century Classroom

Elroy gets in trouble with his robot teacher as we recap the final episode from its first season

![]()

This is the last in a 24-part series looking at every episode of “The Jetsons” TV show from the original 1962-63 season.

The final episode of the first season (and only season until a mid-1980s revival) of “The Jetsons” originally aired on March 17, 1963, and was titled “Elroy’s Mob.”

In the opening sequence of each episode of “The Jetsons” we see young Elroy dropped off at the Little Dipper School. Down he goes, dropped from the family car in his little bubble top flying saucer; his purple and green lunchbox in hand. Despite this, viewers of the show don’t get many peeks at what education in the future is supposed to look like. All of that changes in the last episode. Here the story revolves around Elroy’s performance in school and a bratty little kid named Kenny Countdown. It’s report card day (or report tape, this being the retrofuture and all) and the obnoxious Kenny swaps Elroy’s report tape (which has all A’s) for his own (which not only has four D’s and an F, but also an H).

Elroy brings his report tape home and naturally gets in trouble for getting such low marks. The confusion and anger are settled after Kenny’s dad makes him call the Jetsons on their videophone and explain himself. But by then the damage had been done. Elroy ran away from home with his dog Astro and proceeded to get mixed up with some common criminals. (Based on the last 24 episodes of the Jetsons you wouldn’t be blamed for thinking that maybe 50 percent of people in the year 2063 are mobsters, bank robbers and thieves.)

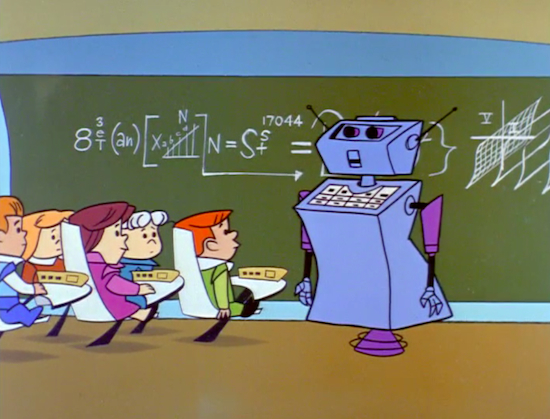

A robot teaches Elroy Jetson and a class of the future (1963)

All of this trouble with the boys’ report tapes starts in the classroom, where Elroy’s teacher is passing out the tapes. According to little Elroy: “And eight trillion to the third power times the nuclear hypotenuse equals the total sum of the triganomic syndrome divided by the supersonic equation.” Elroy’s teacher, Ms. Brainmocker, praises little Elroy for his correct answer (perhaps gibberish is rewarded in the future?). But we have reason to believe that maybe Elroy’s answer isn’t correct. You see, his teacher is having a tough day because she’s malfunctioning. Because Ms. Brainmocker is a robot.

Aside from the vicious fights over racial segregation in our nation’s schools, one of the most pressing educational concerns of the 1950s and ’60s was that the flood of Baby Boomers entering school would bring the system to its knees. New schools were being built at an incredibly rapid pace all across the country, but there just didn’t seem to be enough teachers to go around. Were robot teachers and increased classroom automation the answers to alleviating this stress?

As Lawrence Derthick told the Associated press in 1959, the stresses of the baby boom would only get worse in coming years with more kids being born and entering school and the number of teachers unable to keep pace with this population explosion: “1959-60 will be the 15th consecutive year in which enrollment has increased. He added this trend, with attendant problems such as the teacher shortage, is likely to continue for many years.”

Other than the Jetsons, what visions of robot teachers and so-called automated learning were being promised for the school of the future?

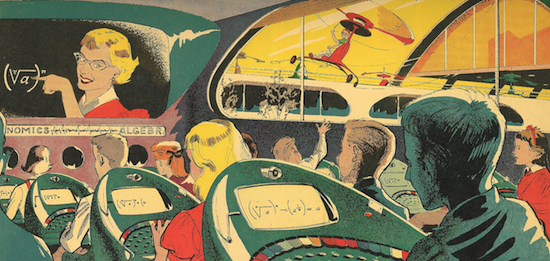

“Push-button education” in the May 25, 1958 edition of the Sunday comic “Closer Than We Think” (Source: Novak Archive)

Arthur Radebaugh‘s classic futuristic comic strip “Closer Than We Think” (1958-63) looked at the idea of automation in the classroom. Movies, “mechanical tabulating machines” and teachers instructing by videophone were all envisioned for the classroom of tomorrow. Each child sits in front of a console which has a screen displaying equations, multiple colored buttons and what looks like maybe a video camera or microphone mounted on the top-center of the desk.

From the May 25, 1958 edition of “Closer Than We Think”:

Tomorrow’s schools will be more crowded; teachers will be correspondingly fewer. Plans for a push-button school have already been proposed by Dr. Simon Ramo, science faculty member at California Institute of Technology. Teaching would be by means of sound movies and mechanical tabulating machines. Pupils would record attendance and answer questions by pushing buttons. Special machines would be “geared” for each individual student so he could advance as rapidly as his abilities warranted. Progress records, also kept by machine, would be periodically reviewed by skilled teachers, and personal help would be available when necessary.

The Little Dipper School, which Elroy Jetson attends (1963)

But visions of automated classrooms and robot teachers weren’t exactly comforting predictions to many Americans. The idea of robot teachers in the classroom was so prevalent in the late 1950s (and so abhorrent to some) that the National Education Association had to assure Americans that new technology had the potential to improve education in the U.S., not destroy it.

In the August 24, 1960 Oakland Tribune the headline read “NEA Allays Parent Fears on Robot Teacher”:

How’d you like to have your child taught by a robot?

With the recent splurge of articles on teaching machines, computers and electronic marvels, the average mother may feel that her young child will feel more like a technician than a student this fall.

Not so, reassures the National Education Association. The NEA says it is true that teaching machines are on their way into the modern classroom and today’s youngsters will have a lot more mechanical aids than his parents.

But the emphasis will still be on aid — not primary instruction. In fact, the teaching machine is expected to make teaching more personal, rather than less.

In recent years, teachers have been working with large classes and there has been little time for individual attention. It is believed that the machines will free them from many time-consuming routine tasks and increase the hours they can spend with the pupil and his parents.

The article went on to cite a recent survey showing that there were at least 25 different teaching machines in use in classrooms around the United States. The piece also listed the numerous advantages, including instant feedback to the student about whether their answers were correct and the ability to move at one’s own pace without holding up (or feeling like you’re being held up by) the other students in a class.

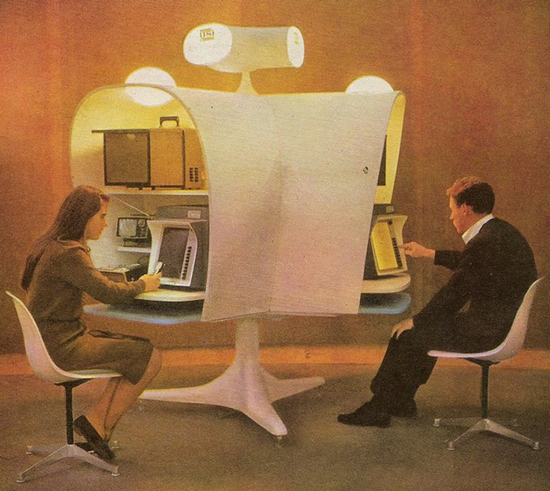

“Automated schoolmarm” at the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair (Source: Novak Archive)

The year after this episode first aired, the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair featured an “automated schoolmarm” at the Hall of Education. The desks and chairs were incredibly modern in design and included plastic molded chairs, a staple of mid-1960s futurism.

From the Official Souvenir Book: “The Autotutor, a U.S. Industries teaching machine, is tried out by visitors to the Hall of Education. It can even teach workers to use other automated machines.”

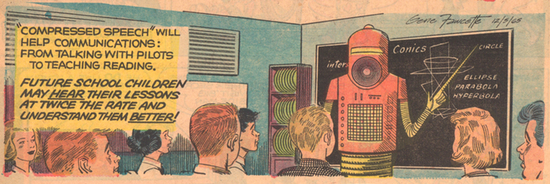

Robot teacher from the December 5, 1965 edition of the Sunday comic strip Our New Age (Source: Novak Archive)

The December 5, 1965 edition of Athelstan Spilhaus‘s comic strip “Our New Age,” people reading the Sunday paper learned about humans’ ability to understand faster speech. This “compressed speech” was illustrated in the last panel of the strip as something that could easily be delivered by robot teacher of the future.

“Compressed speech” will help communications: from talking with pilots to teaching reading. Future school children may hear their lessons at twice the rate and understand them better!

Fast-talking humanoid robots have yet to enter the classroom, but as I’ve said before, we have another 50 years before we reach 2063.

Watching the “billionth rerun” of The Flintstones on a TV-watch device in The Jetsons (1963)

The Jetson family and the Flintstone family would cross paths in the 1980s but there was also a joking nod to the connection between these two families in this episode. The “billionth rerun” of “The Flintstones” is showing on Kenny Countdown’s TV-watch. “How many times have I told you, no TV in the classroom! What do you have to say for yourself?” the robot teacher asks.

In keeping with its conservative leanings, viewers in 1963 are at least assured of one thing — that it doesn’t matter how much well-meaning tech you introduce into a school, kids of the future are still going to goof off.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)