The Lasting Impact of a Civil Rights Icon’s Murder

One of three civil rights workers murdered in Mississippi in 1964 was James Chaney. His younger brother would never be the same

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/indelible_dec08_631.jpg)

In the 44 days that his brother and two other young civil rights workers were missing in Neshoba County, Mississippi, 12-year-old Ben Chaney was quiet and withdrawn. He kept his mother constantly in sight as she obsessively cleaned their house, weeping all the while.

Bill Eppridge, a Life magazine photographer, arrived in Neshoba County shortly after the bodies of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were pulled from the muck of an earthen dam on August 4, 1964. Inside the Chaney home in nearby Meridian, Eppridge felt that Ben was overwhelmed, "not knowing where he was or where he should have been," he recalls. "That draws you to somebody, because you wonder what is going on there."

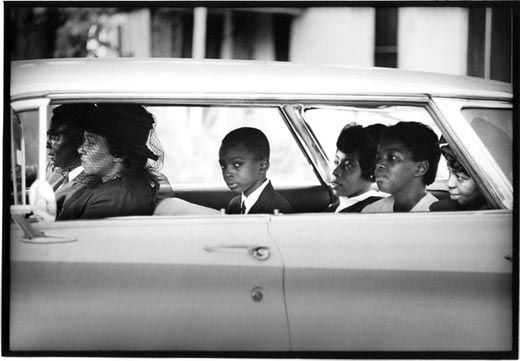

On August 7, Eppridge watched as the Chaney family left to bury their eldest son. As they awaited a driver, Fannie Lee Chaney and her husband, Ben Sr., sat in the front seat of a sedan; their daughters, Barbara, Janice and Julia, sat in the back with Ben, who hunched forward so he'd fit.

Eppridge took three frames. As he did so, he could see Ben's bewilderment harden into a cold stare directed right at the lens. "There were a dozen questions in that look," Eppridge says. "As they left, he looked at me and said, three times, 'I'm gonna kill 'em, I'm gonna kill 'em, I'm gonna kill 'em.' "

The frames went unpublished that year in Life; most news photographs of the event showed a sobbing Ben Chaney Jr. inside the church. The one on this page is included in "Road to Freedom," a photography exhibit organized by Atlanta's High Museum and on view through March 9 at the Smithsonian's S. Dillon Ripley Center in Washington, D.C., presented by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Chaney, now 56, cannot recall what he told Eppridge in 1964, but he remembers being livid that his mother had to suffer and that his father's generation had not risen up years before so that his brother's generation wouldn't have had to. "I know I was angry," he says.

Ben had lost his idol. Nine years older, James Earl Chaney—J.E., Ben called him—had bought Ben his first football uniform and taken him for haircuts. He had taken Ben along as he organized prospective black voters in the days leading to Freedom Summer. Ben, who had been taken into custody himself for demonstrating for civil rights, recalls J.E. walking down the jailhouse corridor to secure his release, calling, "Where's my brother? "

"He treated me," Ben says, "like I was a hero."

After the funeral, a series of threats drove the Chaneys from Mississippi. With help from the Schwerners, Goodmans and others, they moved to New York City. Ben enrolled in a private, majority-white school and adjusted to life in the North. But by 1969 he was restless. In Harlem, he says, he was elated to see black people running their own businesses and determining their own fates. He joined the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army.

In May 1970, two months shy of 18, Chaney and two other young men drove to Florida with a vague plan to buy guns. Soon, five people, including one of their number, were dead in Florida and South Carolina.

Chaney said he didn't even witness any of the slayings. He was acquitted of murder in South Carolina. But in Florida—where the law allows for murder charges to be brought in crimes that result in death—he was convicted of murder in the first degree and sentenced to three life terms.

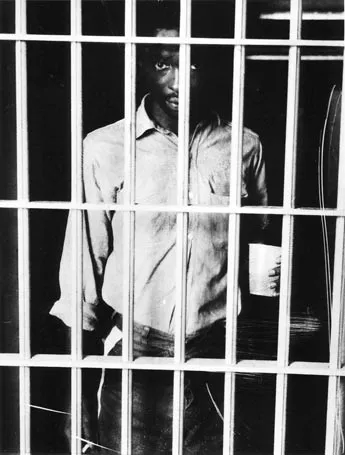

One of his first visitors in jail was Bill Eppridge. Before setting up his cameras, Eppridge fired off a quick Polaroid. His editor liked the Polaroid best. Life readers saw Ben Chaney with his eyes framed by prison bars. "He just looks scared," says Eppridge, who, after the weekly Life folded in 1972, went to work for Sports Illustrated.

"I can imagine I was afraid," Chaney says. "I was in jail."

He served 13 years. Paroled in 1983, he started the James Earl Chaney Foundation to clean up his brother's vandalized grave site in Meridian; since 1985, he has worked as a legal clerk for former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, the lawyer who secured his parole. He envisions creating a Chaney, Goodman, Schwerner Center for Human Rights in Meridian.

In 1967, eighteen men faced federal charges of civil rights violations in the slayings of Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman. Seven were convicted by an all-white jury, eight were acquitted and three were released after jurors deadlocked. The state of Mississippi prosecuted no one for 38 years. But in 2005—after six years of new reporting on the case by Jerry Mitchell of the Jackson Clarion-Ledger—a sawmill operator named Edgar Ray Killen was indicted on charges of murder.

On June 21, 2005, exactly 41 years after the three men were killed, a racially integrated jury, without clear evidence of Killen's intent, found him guilty of manslaughter instead. Serving three consecutive 20-year terms, he is the only one of six living suspects to face state charges in the case.

Ben Chaney sees it this way: somewhere out there are men like him—accomplices to murder. He did his time, he says, they should do theirs. "I'm not as sad as I was," he adds. "But I'm still angry."

Hank Klibanoff is the author, with Gene Roberts, of The Race Beat, which received the Pulitzer Prize for history last year.