The Legend of Lincoln’s Fence Rail

Even Honest Abe needed a symbol to sum up his humble origins

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Object-Lincoln-Fence-Rail-631.jpg)

Every modern president aspires to emulate Abraham Lincoln, but few have wanted to be measured against him—a leader whose stature grew with the enormousness of the challenges he overcame, and whose violent death added the resonance of Greek tragedy to a historic life.

Remarkably, most of the stories that underlie Lincoln’s legacy seem grounded in fact (in contrast, for example, to the apocryphal tale of George Washington and his cherry tree, invented by biographer Parson Weems). Lincoln, arguably more than Washington, embodies the American dream: an up-from-poverty hero who became a giant not only to Americans but to much of the world. “Washington is very unapproachable,” says Harry Rubenstein, chair of Politics and Reform at the National Museum of American History (NMAH). “His mythic stories are all about perfection. But Lincoln is very human. He is the president who moves us to the ideal that all men are created equal. The many tragedies of his life make him approachable.”

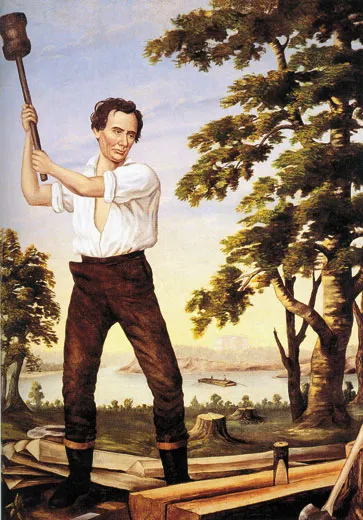

With Lincoln, we can be forgiven for losing sight of the fact that he was also a politician, and in politics, legends rarely emerge spontaneously. A nine-inch, rough-hewn piece of wood, one of 60 artifacts on view through May 30 in the NMAH exhibition “Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life,” serves as an evocative footnote to an epic biography. The object offers a reminder that there was a time when Abe Lincoln, a newcomer to politics, needed a prop that might underscore his humble roots and resonate with voters.

He had no need, however, to invent his back story. Lincoln’s rustic childhood on the frontier, replete with the legendary hours spent studying by firelight, was entirely authentic. And Abe had indeed been as lanky and strong as he was said to have been as a young man in the backwoods. Those who knew him in his youth testified that once when Lincoln arrived in a new town, local rowdies challenged him to a wrestling match—which he won handily.

This was a background that might have carried the day as the Republicans sought their presidential candidate in 1860. But Abe had long since exchanged the rigors of his father’s farm to become a Springfield lawyer. And lawyers were hardly more beloved then than now.

In 1840, presidential candidate William Henry Harrison, emphasizing what he claimed were long-standing ties to the common man (although he came from a family of Virginia aristocrats), had orchestrated what came to be known as the “log cabin campaign.” Harrison’s down-home strategy undoubtedly contributed to his successful run for the presidency. It was a lesson not lost on those advising Lincoln.

In 1860, Lincoln was eager to win the support of the Illinois delegates who would later attend the Republican National Convention in Chicago. Abe’s backers looked for a way to reconnect their man with his genuinely humble roots. They ended up taking a cue from Harrison and staging a nice bit of political theater at the state-level convention in Decatur.

According to Rubenstein, Richard J. Oglesby, a canny Illinois politician and Lincoln supporter, came up with the idea of sending Lincoln’s cousin, John Hanks, back to the family farm in Decatur, Illinois, to collect a couple of the wooden fence rails that he and Abe had split years before. “At a key moment of the state convention,” Rubenstein says, “Hanks marches into the hall carrying two pieces of the fence rail, under which a banner is suspended that reads ‘Abe Lincoln the Rail Splitter,’ and the place goes wild.”

After the state convention threw its support to Lincoln, Hanks returned to the farm and collected more of the hallowed rails. “During the Civil War,” says Rubenstein, “lengths of the rails were sold at what were called ‘Sanitary Fairs’ that raised funds to improve hygiene in the Union Army camps. They were touchstones of a myth.”

The piece of rail now at the Smithsonian had been given to Leverett Saltonstall in 1941, when he was governor of Massachusetts (he later served 22 years in the U.S. Senate). In 1984, five years after Saltonstall’s death, his children donated the artifact, in his memory, to the NMAH. The unprepossessing piece of wood was accompanied by a letter of provenance: “This is to certify that this is one of the genuine rails split by A. Lincoln and myself in 1829 and 30.” The letter is signed by John Hanks.

“If you disassociate this piece of rail from its history,” says Rubenstein, “it’s just a block of wood. But the note by Hanks ties it to the frontier, and to the legend of Lincoln the rail splitter. Actually, he wasn’t much of a rail splitter, but certain artifacts take you back into another time. This one takes you to the days when political theater was just beginning.”

Owen Edwards in a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions.

Editor's Note, February 8, 2011: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the Lincoln family farm was in New Salem, Ill. It is in Decatur, Ill.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)