The Loneliest Shop in the World

Ruins of the Mulka store, in the outback of South Australia. Even at its peak it received only two or three visitors a week and was the only shop in more than 70,000 desolate square miles.

Harrods, in the bustling heart of London, is in a good location for a shop. So is the Macy’s in Herald Square, which boasts of serving 350,000 New Yorkers every day at Christmas time. Whereas down at the Mulka Store, in the furthermost reaches of South Australia, George and Mabel Aiston used to think themselves lucky if they pulled in a customer a week.

Mulka’s proper name is Mulkaundracooracooratarraninna, a long name for a place that is a long way from anywhere. It stands on an apology for a road known as the Birdsville Track—until quite recently no more than a set of tire prints stretching, as the locals put it, “from the middle of nowhere to the back of beyond.” The track begins in Marree, a very small outback town, and winds its way up to Birdsville, a considerably smaller one (“seven iron houses burning in the sun between two deserts”) many hundreds of miles to the north. Along the way it inches over the impenetrable Ooroowillanie sandhills and traverses Cooper Creek, a dried-up river bed that occasionally floods to place a five-mile-wide obstacle in the path of unwary travelers, before skirting the tire-puncturing fringes of the Sturt Stony Desert.

Make your way past all those obstacles, and, “after jogging all day over the treeless plain,” you’d eventually stumble across the Mulka Store, nestled beneath a single clump of pepper trees. To one side of the shop, like some ever-present intimation of mortality, lay the lonely fenced-off grave of Edith Scobie, “died December 31 1892 aged 15 years 4 months”—quite possibly of the sort of ailment that is fatal only when you live a week’s journey from the nearest doctor. To the rear was nothing but the “everlasting sandhills, now transformed to a delicate salmon hue in the setting sun.” And in front, beside a windswept garden gate, “a board sign which announced in fading paint but one word: STORE. Just in case the traveler might be in some doubt.”

Mulka itself stands roughly at the midway point along the Birdsville Track. It is 150 miles from the nearest hamlet, in the middle of a still plain of awesome grandeur and unforgiving hostility where the landscape (as the poet Douglas Stewart put it) “shimmers in the corrugated air.” Straying from the track, which is more than possible in bad weather, can easily be fatal; in 1963, just a few miles up the road from Mulka, the five members of the Page family, two of them under 10 years old, veered off the road, got lost, and died very slowly of thirst a few days later.

That tragedy took place in the height of summer, when daytime temperatures routinely top 125 degrees Fahrenheit for months on end and vast dust storms hundreds of miles across scour the country raw, but Mulka, for all its lonely beauty, is a harsh environment even at the best of times. There is no natural supply of water, and in fact the place owes its existence to an old Australian government scheme to exploit the underground Great Artesian Basin: around 1900, a series of boreholes up to 5,000 feet deep were sunk far below the parched desert to bring up water from this endless underground reservoir. The idea was to develop the Birdsville Track as a droving route for cattle on their way from the big stations of central Queensland to the railheads north of Adelaide, and at its peak, before corrosion of the pipes reduced the flow to a trickle, the Mulka bore was good for 800,000 gallons a day—soft water with an unpleasantly metallic taste that came up under pressure and steaming in the heat, but enough to satisfy all 40,000 head of cattle that passed along the track each year.

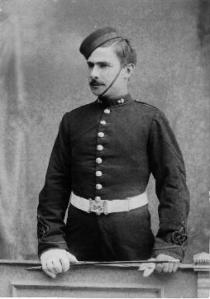

You will not be surprised to learn that George Aiston (1879-1943), the indomitable proprietor of the Mulka Store, was the sort of larger-than-life character who has always flourished in the Australian outback. Returning from service in the Boer War around 1902, Aiston—”Poddy” to his friends—signed up as a constable with the South Australia mounted police and found himself posted to Mungerannie, a spot 25 miles north of Mulka, where he combined the duties of policing the Birdsville Track on camel-back with the role of Sub-Protector of Aborigines. Although he had practically no formal education, Aiston was a man of quick intelligence and surprisingly wide interests; he lectured occasionally on ethnography at the University of Melbourne and corresponded with academics and authorities from all over the world. For some years the Mulka Store was home to a large assortment of medieval armor and what was reckoned to have the best collection of dueling pistols outside Europe, and Poddy was also sympathetic to, and fascinated by, the indigenous peoples of Australia. Over the years, he befriended many of them, learning their languages, and he gradually became a world-renowned expert in their culture, building up a significant collection of Aboriginal artifacts, from spears and throwing sticks and boomerangs to pointing bones (used to work magic and curse enemies) and works of art. It’s very lucky that he did, for Aiston’s years as Sub-Protector of Aborigines coincided with the final collapse of the local culture, and it is largely thanks to the work he did, and the photographs he took, that we know as much as we do about central Austalian folklore and corroborees and rain-making ceremonies, and all the other aspects of traditional nomadic life. Poddy set these details down in 1924 in a book co-written with George Horne that’s still in print and still worth reading: Savage Life in Central Australia.

Scholar though he was at heart, Aiston was by necessity also an intensely practical man. Informed in 1923 that he was to be transferred out of the district he had grown to love, he resigned from the police and, with his wife, took a lease on the land around the Mulka bore. There he built his store by hand, adding to it over the years until it became quite a substantial dwelling. “This house,” he informed a friend in May 1925,

is a queer patchwork of rooms, none of them of the same height and gables running in all directions. I am enlarging the kitchen and dining room and raising them to the level of my store and our bedroom… It is my intention to build two bedrooms on the other side to correspond, and will then pull down the three rooms… for an extension of the dining room and to make a sitting room; it will be rather a nice place when it is finished.

Being the only shop of any kind in a district of well over 70,000 square miles, Aiston and his wife tended to maintain the broadest range of stock imaginable, though inevitably they catered chiefly for the needs of passing drovers and the owners of the cattle stations up and down the track. “My shop often amuses me,” Poddy wrote soon after its opening. “I have just about everything from ribbons to horseshoes. Just above my head there are three pairs of Mexican spurs…. I have enough medicines to stock a chemist’s shop.” For some years he doubled up as a blacksmith and tacksman, shoeing the horses of passing drovers, and it was only in 1927 that he finally found it worthwhile to open up a petrol depot as motor vehicles at last replaced horses and camels as the chief means of transportation on the track. As late as 1948, shortly after Poddy’s death, when the writer George Farwell called on Mrs. Aiston at the Mulka Store, the stock remained a source of quiet astonishment, and though the customer base remained minuscule, the few who did call would spend anywhere from £25 to £60 a time—that when £25 was still a large sum of money.

Here was a real bush store, with all manner of interesting goods; alongside bags of flour and sugar were bridles, bush blankets, shining new quartpots, Bedourie camp-ovens, round cheeses, waterbags, and some boxes of old-style phonograph cylinders, manufactured when Sousa’s Band first stirred the world.

The round cheeses are not such a strange addition to the stock as they at first appear; they were the fast food of their day, ideal tucker for drovers trekking up and down the track on horseback. There are clues, nonetheless, that the Aistons’ eccentricities were eventually exacerbated by the isolation and the heat. Tom Kruse, the renowned mailman of the Birdsville Track, who made the journey from Marree to the Queensland border once a fortnight in a lorry laden with letters and supplies, remembered that “for years old Poddy used to have a standing order for condensed milk and nectarines. Might be a few, might be half a ton.” Despite this, Kruse—himself an eternally resourceful character—retained an immense respect for Aiston. “He was a most remarkable man and he would have been a legend no matter where he lived,” he said. “It just seemed that the Birdsville Track was the most unlikely place in the world to find such an extraordinary personality.”

Even Poddy Aiston, though, could not control the weather, and though his store got off to a profitable start—the penny-an-animal he charged drovers to water their cattle at his borehole mounted up—he and his wife were nearly ruined by the record drought that quickly destroyed the lives of almost every outback dweller between 1927 and 1934. Before the long rainless period set in, there were cattle stations all along the Birdsville Track, the nearest of them only nine miles from Mulka, but gradually, one by one, the drought destroyed the profitability of these stations and the owners were forced to sell up or simply to abandon their properties. As early as 1929, the Aistons had lost practically their entire customer base, as Poddy confessed in another letter, this one written in the southern summer of 1929:

This drought is the worst on record…. There is no-one left on the road between here and Marree, all the rest have just chucked it up and left. Crombie’s place is deserted and there is only one other house above that to Birsdville that is occupied.

Aiston and his wife stayed put, struggling to make a living, but their hopes of an early and comfortable retirement were shattered by the seven-year drought, and the couple had no option but to stay in business until Poddy’s death in 1943. After that, Mabel Aiston continued to run the store for eight more years, finally retiring, in her middle 70s, in 1951. For a long time, it seems, she had resisted even that, telling George Farwell that she felt too attached to the land to leave it.

For Farwell, she was the perfect shopkeeper:

The years seemed to have overlooked Mrs. Aiston, for at the age of 73 she looked as fresh and light-hearted as when I had first met her, despite her lonely widowed life and the trying heat of summer. She greeted me as casually as if I had only been absent a few days; we took up a year-old conversation where we had left off…. With her grey hair, spectacles, apron, neatly-folded hands and quiet friendliness across the counter of her store, she reminded one of the typical shopkeeper of the small suburbs, where kiddies go for a bag of lollies or a penny ice-cream. That is, until you heard her begin to talk about this country, which she loved.

She wasn’t isolated, she insisted, for now that the drought had finally broken the track had grown busier—indeed, after years of nothingness, it now seemed to be almost bustling again:

There’s plenty of people passing here. Tom Kruse comes up each fortnight, and usually he has somebody new with him. Besides, Ooriwilannie’s only nine miles up the track. You know the Wilsons have moved in there now? They’re always driving down to see how I am. They’ve got to come two or three times a week to get water from the bore.

Sometimes, she added, “I feel I ought to go South. I’d have to go Inside somewhere. But what is there down there for an old woman like me? I’d be lost. I often think I may as well leave my bones here as anywhere.”

She wouldn’t be lonely, after all. She’d still have Edith Scobie, with the Pages yet to come.

Grave of Edith Scobie (1877-1892), Mulka Store. The inscription on her sand-scoured tombstone, huddled beneath a solitary gumtree, reads: "Here lies embalmed in careful parents' tears/A virgin branch cropped in its tender years."

Page family grave, near Deadman's Hill, Mulka. The five members of the family were buried without any sort of ceremony in a trench gouged out by a Super Scooper. The inscription on the aluminium cross reads simply: "The Pages Perished Dec 1963"

Sources

State Library of New South Wales. ML A 2535 – A 2537/CY 605: George Aiston letters to W.H. Gill, 1920-1940; Harry Ding. Thirty Years With Men: Recollections of the Pioneering Years of Transportation in the Deserts of ‘Outback’ Australia. Walcha, NSW: Rotary Club of Walcha, 1989; George Farwell. Land of Mirage: the Story of Men, Cattle and Camels on the Birdsville Track. London: Cassell, 1950; Lois Litchfield. Marree and the Tracks Beyond. Adelaide: the author, 1983; Kristin Weidenbach. Mailman of the Birdsville Track: the Story of Tom Kruse. Sydney: Hachette, 2004.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)