The Men Behind the First Olympic Team

Mocked by their peers and kicked out of Harvard, the pioneering athletes were ahead of their time… and their competition in Athens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/81/b781c969-966a-4a97-87db-70e3ac842c68/usolympicteam-631-6.jpeg)

Years later, it was said that the whole idea started as a joke.

It was January 1896, and at the Boston Athletic Association’s annual indoor track meet at Mechanic’s Hall, Arthur Blake—a 23-year-old distance-running star for the BAA—had just won the hotly contested 1,000-yard race. Afterward, stockbroker Arthur Burnham, a prominent member of the well-heeled association, was congratulating him on his performance. Blake laughed and said in jest, “Oh, I’m too good for Boston. I ought to go over and run the Marathon, at Athens, in the Olympic Games.”

Burnham looked at him for a moment, and then spoke in earnest. “Would you really go if you had the chance?”

“Would I?” Blake responded emphatically. From that moment—or so high jumper Ellery Clark later claimed in his memoirs—Burnham decided that the nine-year-old BAA should send a team to the Games. The result was that the young men from Boston became, in large part, the de facto U.S. Olympic team: the first ever.

The BAA had been founded in 1887 by an eclectic group of former Civil War officers, Boston Brahmins and local luminaries including the celebrated Irish poet and activist John Boyle O’Reilly. With old Yankee wealth as the foundation and forward-minded thinkers at the helm, the Association had in less than a decade risen to become one of the most powerful sports organizations in America.

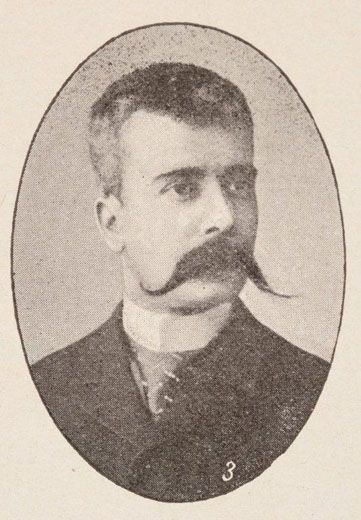

By January of 1896, most everyone in U.S. athletic circles had heard about the plan to revive the ancient Greek Olympic competitions, promulgated by an energetic Frenchman, Baron Pierre de Coubertin. The diminutive, 34-year-old baron was no stranger to the States or to Boston. In fact, he had attended a conference of physical educators held in the city in 1889, where he presented some of his ideas; Coubertin believed in the integration of intellectual discipline with athletic activity.

As a historian, Coubertin knew that an even greater precedent lay in the distant past; in the quadrennial Games held in ancient Olympia. An internationalist, as well, Coubertin began to envision bringing the world together through sports and athletics and a celebration of this classic “sound mind, sound body” tradition. He presented his ideas at a “jubilee” of French sports organizations held at the Sorbonne in November of 1892.As historian Richard D. Mandell described it in his 1976 book on the first modern Olympic Games, Coubertin had intended that the last paragraphs of his speech would have the greatest impact. Here, the baron’s passions—physical culture, history, Hellenism, internationalism, British public schools—converged to form the spark of his great, earthshaking idea:

“It is clear that the telegraph, railroads, the telephone, dedicated research congresses and expositions have done more for peace than all the treaties and diplomatic conventions. Indeed, I expect that athleticism will do even more.

Let us export our rowers, our runners and our fencers: that will be the free trade of the future. When the day comes that this is introduced... the progress toward peace will receive a powerful new impulse.

All this leads to what we should consider the second part of our program. I hope you will help us... pursue this new project. What I mean is that, on a basis conforming to modern life, we reestablish a great and magnificent institution, the Olympic Games.”

“That was it!” wrote Mandell. “This was Coubertin’s first public proposal for the ultimate step in the internationalization of sport.” As is often the case with bold, new ideas, it was met at first with puzzlement and derision. But Coubertin was tireless in promoting his vision, and four years later, by the time Arthurs Blake and Burnham had their fateful interchange on the track, the first Modern Games were taking shape, and would be held in Athens in April.

There was no official U.S. Olympic team in 1896. But there was a BAA team that would make up the majority of the American delegation. Interestingly, some of the other powerhouses—most notably the BAA’s archrival from New York—declined to participate. The New York Athletic Club had just defeated the London AC in an epic track meet in New York the previous fall. Beating the Brits in front of thousands of fans was big—who cared about some silly, shoestring-budget event in far-off Athens? That wasn’t a minority opinion, either. “The American amateur sportsman in general should know that in going to Athens he is taking an expensive journey to a third rate capital where he will be devoured by fleas,” sniffed the New York Times.

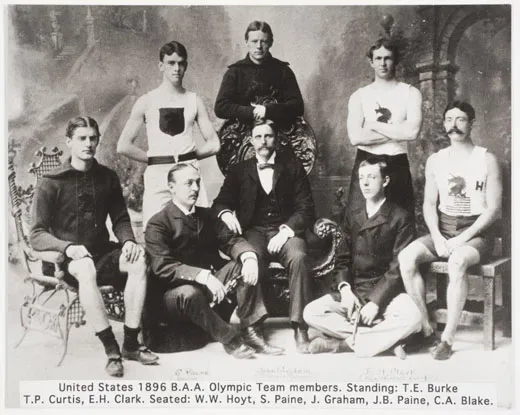

Yet, some people—like Blake, like Ellery Clark, like Burnham—saw something else; a chance to be part of something significant, maybe even historic. The association supported the idea, and an all-star team from the BAA was selected:

Arthur Blake, middle- and long-distance runner

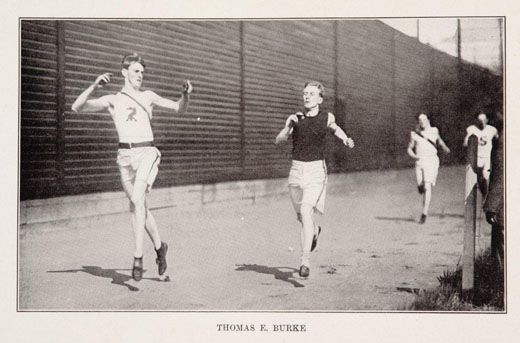

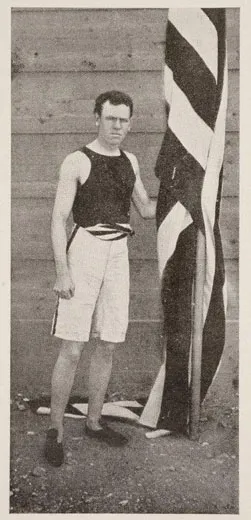

Tom Burke, sprinter and middle-distance runner

Ellery Clark, high jumper

Thomas P. Curtis, hurdler

W. H. Hoyt, pole vault

Accompanying the team would be John Graham, the coach of the BAA track team. Born in Liverpool in 1862 and a prominent sprinter in England, he emigrated to the U.S. while still a teenager. He was hired as an assistant by the pioneering physical educator Dr. Dudley Sargent at Harvard; the same Dudley Sargent who would later create and furnish both Harvard’s Hemenway Gymnasium and the state-of-the-art training facilities at the B.A.A’s opulent clubhouse, located on Boylston Street. Graham worked at Harvard for three years before going on to become the trainer (coach) at Brown University and Princeton (he would return to Harvard as track coach in the early 1900s).

Having served under Sargent, Graham was steeped in the most innovative ideas about training and exercise at the time.

The other members of the BAA who decided to compete in 1896 were not track athletes: John Paine and his brother Sumner were club members, along with their father, Charles Jackson Paine, a true BAA Brahmin. The elder Paine had been an oarsman for Harvard in the 1850s, and served as an officer in the 22nd Massachusetts in the Civil War, during which time he commanded a unit of African-American soldiers.

When he heard about the other athletes heading to Athens, his son John—a crack pistol shot—decided to go and compete in the shooting events that were also on the program for the Modern Games. He apparently traveled separately from Burke, Blake, Clark and the others, because he first went to Paris, where Sumner was working for a gunsmith, and persuaded his brother to accompany him to Athens.

Most of the rest of the 14-man American team that competed in 1896 were made up of young men from Princeton—where Prof. William Sloane, a friend of Coubertin’s, had championed the idea of the Olympic revival in the U.S.—plus one feisty and fiercely independent athlete from South Boston, James B. Connolly, who competed proudly in the hop, step and jump (the event now known as the triple jump) for the tiny Suffolk Athletic Club.

Like the BAA itself, the Boston contingent of the American team had strong Harvard connections. Clark was still a senior at the university, where he was a star all-around track athlete. He had to ask permission from his dean to interrupt his studies for eight weeks in the middle of the semester in order to travel to Athens. His dean took it under advisement, and when he gave his permission in writing, Clark said, “I gave a shout that could have been heard, I believe half way to Boston.”

Connolly’s departure from Harvard was on a much different note. “I went to see the chairman of the athletic committee about a leave of absence,” he recalled in his 1944 autobiography. “One peek at the chairman’s puss told me here was no friendly soul.”

The chairman questioned his motives for attending the games, implying that he was simply looking for an opportunity to gallivant through Europe. Connolly recounted the exchange:

“You feel that you must go to Athens?”

“I feel just that way, yes, sir.”

“Then here is what you can do. You resign and on your return, you make reapplication to the college, and I will consider it.”

To that, I said: ‘I am not resigning and I’m not making application to re-enter. I’m through with Harvard right now. Good day!’

It was ten years before I again set foot in a Harvard building, and then it was as a guest speaker of the Harvard Union; and the occasion nourished my ego no end."

Just before the BAA members were set to depart for Athens, there was a crisis: Burnham’s efforts to raise money to pay for the trip had fallen short. The BAA’s politically connected and deep-pocketed membership saved the day. Former governor of Massachusetts Oliver Ames, a longtime BAA member, jumped in and managed to marshal the funds to cover the shortfall in three days.

As John Kieran and Arthur Daley wrote in their 1936 Story of the Olympic Games:

“With passage paid and enough money to provide board and lodging in Greece and return tickets to Boston, the little team started on what was to be a triumphal journey and the beginning of United States ascendancy in the modern Olympic Games.”

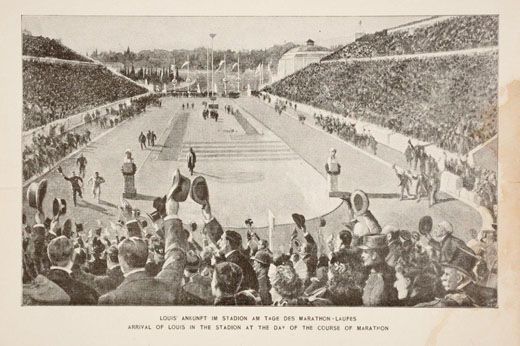

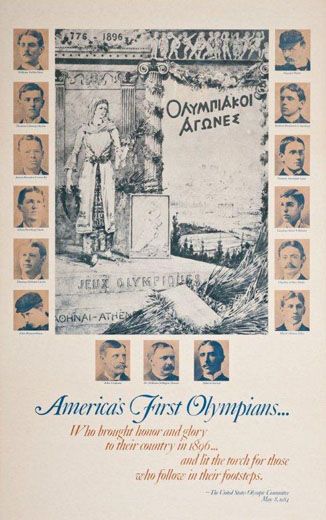

The BAA athletes dominated the first Olympic Games, winning six of the 11 first-place track-and-field medals accrued by the U.S. team (there was no “going for the gold” in the first Olympics; winners received silver medals). The crusty Connolly—technically not an Association member, but part of the Boston contingent, nonetheless—had the distinction of being the first man in the Modern Olympics to win an event, as the hop, step and jump was held early in the program.

In addition to their “athletics” (track–and-field) teammates, BAA members John and Sumner Paine each won first-place medals in the shooting events.

The fresh-faced, young BAA team was also a big hit with the Athenians, who imitated their “rah rah” college-type cheers; and feted and celebrated them throughout the time they were there.

Perhaps their most lasting contribution, however, was what the team brought back. The entire squad was in the Olympic stadium to watch the finish of the marathon, the final event of the 1896 Games, which was won by a Greek. They were so impressed by the drama of this event they came home with the idea of staging a similar long-distance running race in the U.S. The BAA coach Graham and Tom Burke, who had won two events, the 100 and the 400 meters, in Athens, spearheaded the effort. A year later, in April 1897, the first BAA Marathon was held. Now known as the Boston Marathon, the race attracts 25,000 participants a year and is one of the country’s longest-running annual sports events.

Excerpted from: “The BAA at 125: The Colorful, 125-Year History of the Boston Athletic Association” by John Hanc, to be published later this year by Skyhorse Publishing. For more information or to reserve a copy, visit http://www.skyhorsepublishing.com