The Midday Ride of Paul Revere

Longfellow made the patriot’s ride to Lexington legendary, but the story of Revere’s earlier trip to Portsmouth deserves to be retold as well

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Paul-Revere-Portsmouth-New-Hampshire-631.jpg)

Colonial Boston’s secret patriot network crackled with the news. Regiments of British troops were on the move, bound for points north to secure military supplies from the rebels. Paul Revere mounted his horse and began a feverish gallop to warn the colonists that the British were coming.

Except this ride preceded Revere’s famous “midnight ride” by more than four months. On December 13, 1774, the Boston silversmith made a midday gallop north to Portsmouth in the province of New Hampshire, and some people—especially Granite Staters—consider that, and not his trip west to Lexington on April 18, 1775, as the true starting point of the war for independence.

With talk of revolution swirling around Boston in the final days of 1774, Revere’s patriot underground learned that King George III had issued a proclamation that prohibited the export of arms or ammunition to America and ordered colonial authorities to secure the Crown’s weaponry. One particularly vulnerable location was Fort William and Mary, a derelict garrison at the mouth of Portsmouth Harbor with a large supply of munitions guarded by a mere six soldiers.

When Boston’s Committee of Correspondence, a local group of citizens opposed to British rule, received intelligence that British General Thomas Gage had secretly dispatched two regiments by sea to secure the New Hampshire fort—a report that was actually erroneous—they sent Revere to alert their counterparts in New Hampshire’s provincial capital. Just six days after the birth of his son Joshua, Revere embarked on a treacherous wintry journey over 55 miles of frozen, rutted roads. A frigid west wind stung his cheeks, and both rider and steed endured a constant pounding on the unforgiving roadway.

Late in the afternoon, Revere entered Portsmouth, a major maritime trading port that had recently imported Boston’s hostility to the royal government. He drew his reins at the waterfront residence of merchant Samuel Cutts, who immediately convened a meeting of the town’s own Committee of Correspondence. With Revere’s dispatch in hand, Portsmouth’s patriots plotted to seize the gunpowder from Fort William and Mary the following day.

Learning of Revere’s presence in the capital, New Hampshire’s royal governor, John Wentworth, suspected something was afoot. He alerted Capt. John Cochran, the commander of the small garrison, to be on guard and dispatched an express rider to General Gage in Boston with an urgent plea for help.

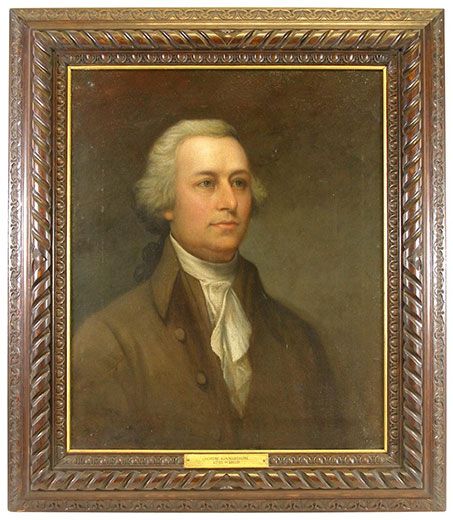

The next morning, the steady beat of drums reverberated through the streets of Portsmouth, and 200 patriots soon gathered in the town center. Ignoring the entreaties of the province’s chief justice to disperse, the colonists, led by John Langdon, launched their boats into the icy Piscataqua River and rowed toward the fort on the harbor’s Great Island.

The logistics of overtaking a woefully undermanned fort were not daunting, but the sheer brazenness of the mission, and its dire consequences, should have given the men some pause. As the chief justice had just warned, storming the fort “was the highest act of treason and rebellion they could possibly commit.”

A snowstorm cloaked the colonists’ amphibious attack and muffled the rhythmic dipping of hundreds of oars as they approached the fort. When the patriots came ashore around 3 in the afternoon, they were joined by men from neighboring towns to form a force of approximately 400.

Langdon, a future New Hampshire governor and signer of the United States Constitution, demanded that Cochran hand over the fort’s gunpowder. Despite being outnumbered, the commander refused to yield without a fight. “I told them on their peril not to enter,” Cochran wrote to Wentworth. “They replied they would.”

Cochran ordered the five soldiers manning the ramparts “not to flinch on pain of death but to defend the fort to the last extremity.” On his command, the soldiers fired muskets and three four-pound cannons, but the shots missed the invaders. Before the troops could fire again, the patriots swarmed over the walls from every side and broke down the doors with axes and crowbars. The provincial soldiers put up a valiant fight—even Cochran’s wife wielded a bayonet—but math was not on their side. “I did all in my power to defend the fort,” Cochran lamented to Wentworth, “but all my efforts could not avail against so great a number.”

The patriots detained the soldiers for an hour and a half as they loaded 97 barrels of His Majesty’s gunpowder onto their boats. With a chorus of three cheers, the rebels defiantly lowered the King’s colors, an enormous flag that had proudly proclaimed British dominion over the harbor, and released the prisoners before dissolving into the falling snow as they rowed back to Portsmouth.

Couriers bearing news of the attack circulated through the New Hampshire countryside and recruited volunteers to retrieve the remaining armaments before British reinforcements could arrive. The following day, more than 1,000 patriots descended upon Portsmouth, turning the provincial capital of 4,500 people into a rebel hotbed.

Wentworth ordered his militia’s commanding officers to recruit 30 men to reinforce the fort. They couldn’t even scrounge up one, no doubt because many members were participants in the uprising. “Not one man appeared to assist in executing the law,” a disgusted Wentworth wrote in a letter. “All chose to shrink in safety from the storm, and suffered me to remain exposed to the folly and madness of an enraged multitude, daily and hourly increasing in numbers and delusion.”

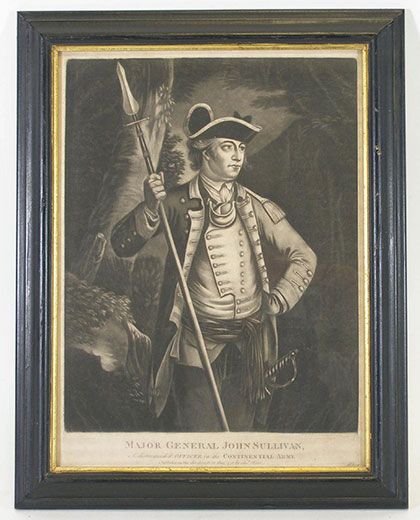

That evening, hundreds of patriots led by John Sullivan, himself a provincial militia major and a delegate to the Continental Congress, again shoved off for the island garrison. Facing a force more than double that of the previous day, Cochran realized this time that he could not even muster a token defense. He watched helplessly as the colonists overran the installation and worked straight through the night loading their plunder.

By the time they left the next morning, Sullivan’s men had seized 16 pieces of cannon, about 60 muskets, and other military stores. The booty was disseminated through New Hampshire’s serpentine network of interior waterways on flat-bottomed cargo carriers called “gundalows” and hidden in hamlets throughout the region.

British reinforcements finally arrived on the night of December 17 aboard the HMS Canceaux, followed by the frigate HMS Scarborough two nights later. The uprising was over, but the treasonous assault was humiliating for the Crown, and Revere was a particular source of its ire. Wentworth wrote to Gage that the blame for the “false alarm” rested with “Mr. Revere and the dispatch brought, before which all was perfectly quiet and peaceable here.”

A plaque at the fort, now named Fort Constitution, declares it as the location of the “first victory of the American Revolution.” Other rebellious acts, such as the torching of the HMS Gaspee in Rhode Island in 1772, preceded it, but the raid on Fort William and Mary was different in that it was an organized, armed assault on the King’s property, rather than a spontaneous act of self-defense. Following the colonists’ treasonous acts in Portsmouth Harbor, British resolve to seize rebel supplies only strengthened, setting the stage for what happened four months later at Lexington and Concord.